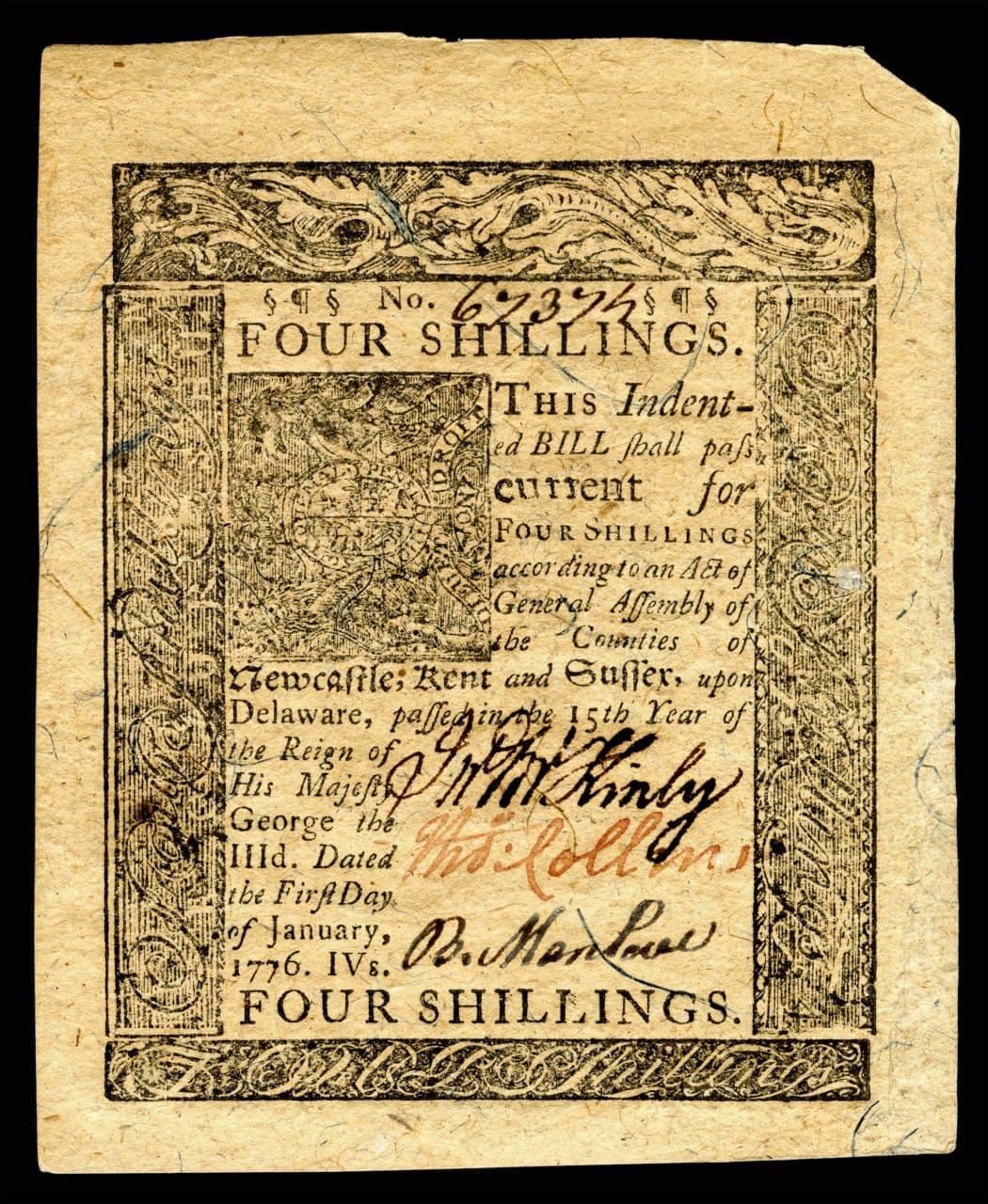

It’s January, 1776. You’re a printer in Delaware, one of thirteen restive American colonies chafing against British rule. The Continental Congress, the colonies’ nascent collective government, has recently passed an act creating its own currency and you’ve been tasked with creating Delaware’s issue of banknotes.1 This is your response:

Bearing the incongruous declaration that the Delaware pound was created “in the 15th Year of the Reign of His Majesty George the IIId”, this 4-shilling note is one of a plethora of “Continental” banknotes issued from 1775 onwards to bankroll the American Revolution. Today, we’d call these Continental notes a fiat currency — that is, a monetary system whose value is managed by a central bank, rather than being vested in a precious commodity such as silver or gold — but Revolutionary-era America was not quite ready for this financial innovation. The colonial governments declared that their Continental dollars (or Continental pounds, as Delaware called them) were backed by future tax revenues, but a jittery populace was unconvinced and the value of paper notes, relative to hard currency such as Spanish silver dollars, dropped five hundredfold in only six years.2 Nor was this the only problem undermining the new currency.

Let’s take a look again at the note above. It may lack the “To Counterfeit, is DEATH” slogan printed on some other Continental notes,3 but that doesn’t mean it would have presented much of a challenge for a skilled counterfeiter.4 Forgers had access to much of the same technology used to produce the notes, such as movable type and copperplate engraving, and that made paper money an easy target. The security measures available to the institutions that issued banknotes were limited to such things as hand-cut type ornaments and detailed engravings, all of which made copying a note a time-consuming process. Some states reissued notes on a yearly basis, with each year’s design distinct from the last, in an effort to stay ahead of the forgers. As long as the time it took to copy a note made it uneconomical for a counterfeiter to do so, that denomination was safe; the instant it had been copied, it was dead in the water.5

Now, our Delaware printer was not exactly a security expert. The engraved panels surrounding the note’s central text might have kept a forger at bay for some time, but the text itself is woefully undistinguished. Up at the top is a sort of cargo-cult attempt at using type ornaments to discourage copying: two section signs and a pilcrow (§ ¶ §) stand sentry at either side of the banknote’s handwritten serial number. Not the most unusual characters, nor the most difficult to copy.

All this spelled disaster for the Continental currency. Unmoored from a silver or gold standard and woefully easy to copy, by 1781 Continental banknotes were barely worth the paper they were printed on. They were, in the parlance of the day, “not worth a Continental”.4 It was not until 1792, when the first U.S. Mint was established in Philadelphia to produce gold, silver and copper coins, that the States’ common currency began to settle on an even keel — and the glorious Continental banknote, earnest, inadequate pilcrows and all, was no more.6

Many thanks to Jason Black, who tweets at @p2p_editor, for his original tweet about all this. Also, you can see many more fascinating images of Continental banknotes at Eric Grundhauser’s article at Atlas Obscura, “The Ornate Charm of American Currency from the 1700s”.

- 1.

-

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. “Continental Congress, 1774–1781”. Accessed April 23, 2016.

- 2.

-

McLeod, Frank Fenwick. “The History of Fiat Money and Currency Inflation in New England from 1620 to 1789”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 12 (1898): 57-77.

- 3.

-

Grundhauser, Eric. “The Ornate Charm of American Currency from the 1700s”. Atlas Obscura.

- 4.

-

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. “Colonial and Continental Currency: A New Nation’s Currency”.

- 5.

-

Lynch, Jack. “The Golden Age of Counterfeiting”. Colonial Willamsburg.

- 6.

-

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. “Money in Colonial Times”. Accessed April 23, 2016.

Comment posted by H James Lucas on

Tobias Frere-Jones’s 2015 lecture “In Letters We Trust” should prove to be a captivating 45 minutes for anyone interested in typographic security measures on currency.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Thanks for the link! I can’t believe I didn’t know about that talk already — it’s now at the top of my queue.

Comment posted by Michael Anthony Scott on

Very interesting article.

What it drives home to me, is that the worth of any fiat currency is based on the ideals of faith in the nation state … faith that the state will honor it / stand behind it/ promote it. These are the same problems facing many nations across the world today. If I understand the economic problem correctly, the complexity of establishing a national economy must go beyond gold bullion,i.e., there just isn’t enough of it, it’s too cumbersome, and the levels of transactions too vast. So, paper, type, and a fiat system is here to stay.

No matter what, it’s fun to catch an historical glimpse of a developing nation’s attempt to play with the big boys, and then to become the ultimate big boy a few centuries later.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Michael — the concept of a fiat currency is a slippery one, but that’s a good way to put it. I’m glad you enjoyed the article, and thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

Perhaps there were some Tories in the Delaware government or print shop, or perhaps this series of notes was aimed at Tory sympathizers. Note the engraving of an English royal seal, complete with “Dieu et mon droit” — not a Revolutionary sentiment!

On the other hand, the arms are printed sideways. A snarky insult to the king?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Perhaps! Or might it have been a calculated sop to the British authorities so that they did not interfere with the Continental Congress’s ability to raise funds? Disclaimer: I am emphatically not a historian of the American Revolution. Maybe some other readers know what was going on here?