“An ivory what?” you may well ask. In the process of researching and writing The Book (which is, need I say, available from all good bookshops, I came across any number of tidbits that lay just fractionally below the interesting-ness threshold required for inclusion in the book. One discovery in particular, though, has had me kicking myself since I first handed in the manuscript back in 2015, and I still wish I’d found a way to incorporate it into the narrative. Here it is!

Writing media have always been defined by a tension between cost, quality and utility. In ancient China, for example, writers had to choose between tall, narrow strips of bamboo or larger sheets of silk as their writing medium.1 Bamboo was cheap and plentiful and, strung into mats unrolled from right to left, it was the driving force behind the East Asian convention of writing text from top to bottom rather than left to right. Its principal drawback was that it was also very heavy. A learned Chinese reader was said to have read many cartloads of books, emphasising their weight rather than their quantity.2 Featherweight silk, on the other hand, was expensive to buy but exquisite to write upon, and was preferred for elaborate illustrations or important documents.3 (Paper, when it arrived, split the difference between the two, but that’s another story.)

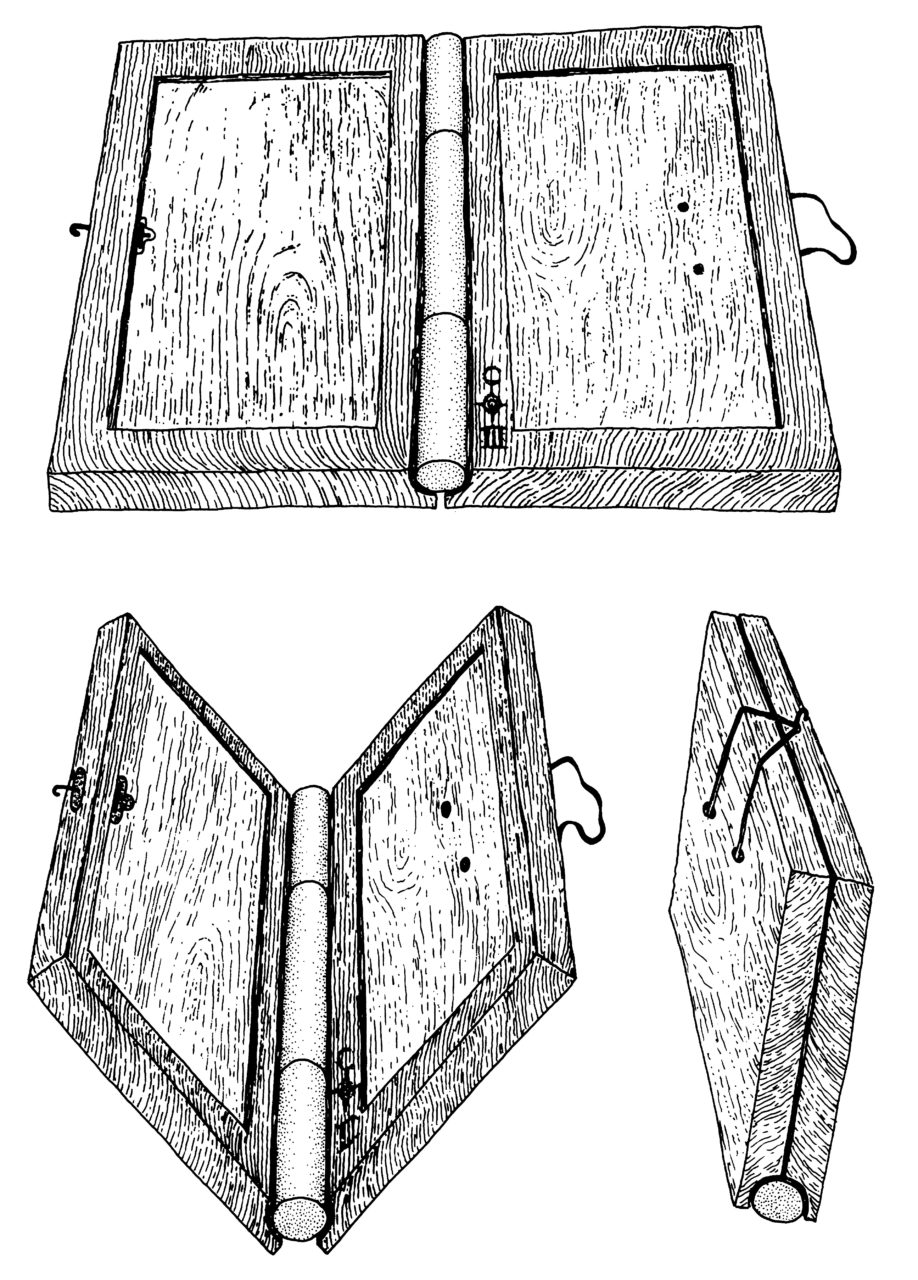

The Greco-Roman experience was similar. Though the conventional view of an ancient scribe is of a writer toiling over an unrolled papyrus scroll, papyrus was neither versatile nor robust enough for everyday use: it was fragile, sometimes wearing away against a reader or writer’s clothes, and it required a flat surface on which to write.4,5 The average Roman-about-town relied instead on a diptych, or writing tablet, fashioned from a pair of hinged pieces of wood hollowed out to hold a thin layer of beeswax, in which they wrote with a simple pointed stylus. Back at home, their notes could be copied onto papyrus for safekeeping and then erased from their diptych with the other end of the stylus, which was flattened like a spatula for just that purpose.5 Like the ancient Chinese, the Romans had to choose between strong and delicate, cheap and expensive, portable and static.

What does this have to do with Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father and third President of the United States of America, and what was his ivory “polyptych”? The clue is in the name. In a general sense, diptych means “folded in two”, but for the Greeks it carried the specific connotation of a folding, two-part writing tablet. (Today it is more often applied to bipartite paintings such as altarpieces.)6 Triptych means “threefold” and polyptych, by extension, “manifold”. An ivory polyptych, then, is an ivory notebook of many pages — and that is exactly what Jefferson used each day to record temperature, wind direction, weather, bird migrations and many other indicators of the climate and season.

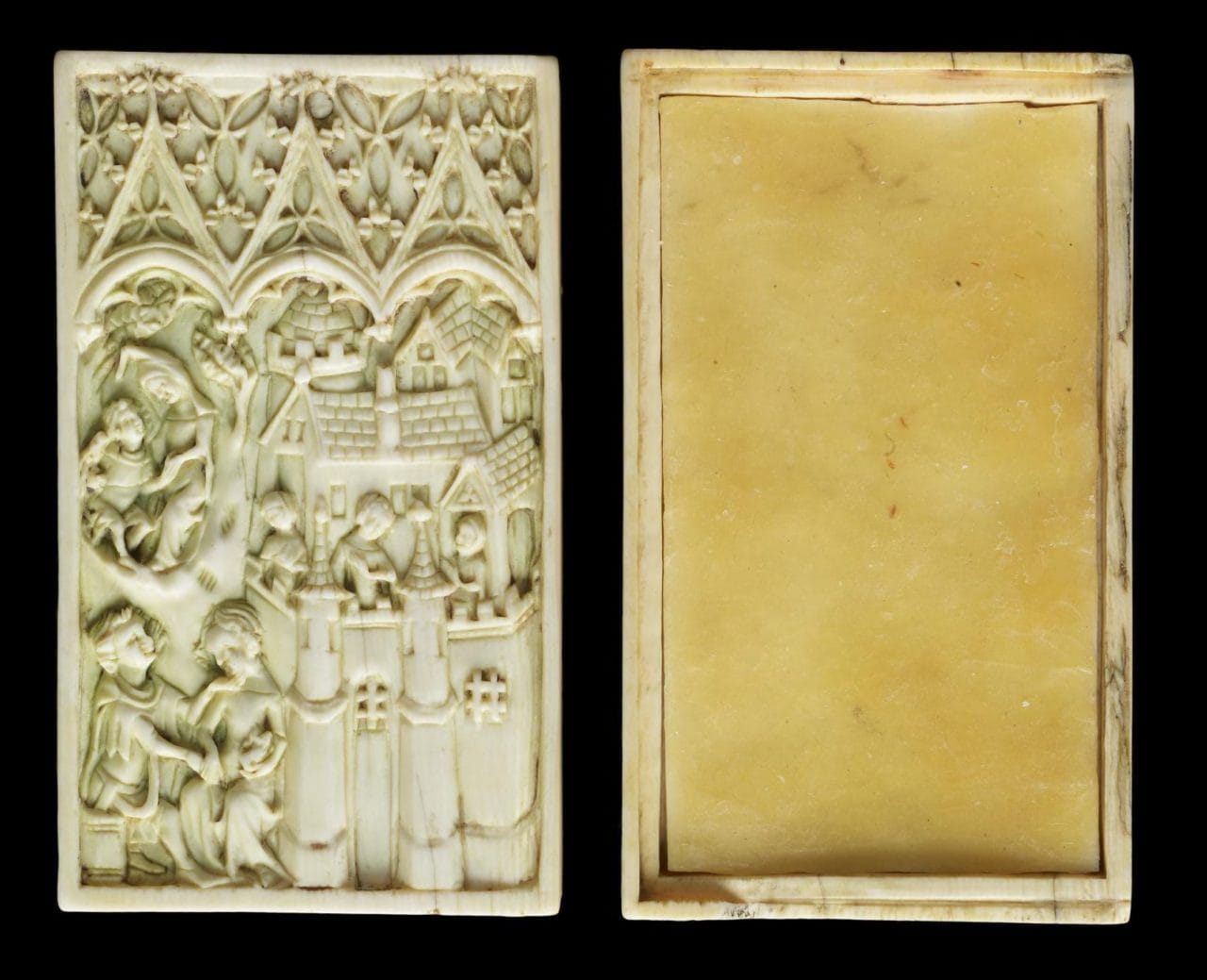

Jefferson was following a long-held tradition. Portable, erasable writing tablets continued to be used from Roman times onward (there’s a particularly fine medieval example shown here, barely a few inches on a side), while ivory notebooks in particular became fashionable in the 18th and 19th centuries. Robert Payton, late of the Museum of London, and who kindly provided the image of the Uluburun writing set above, told me that they were popular with ladies of a certain station in life:

Ladies visiting each other used to keep notes on very small ivory tablets well into the beginning of the 20th century; similar tablets were also used by ladies to mark down dancing partners at formal dances in the 19th century.

Miss Havisham of Dickens’ Great Expectations was one such 19th century lady. Seeking to write an IOU of sorts,

She took from her pocket a yellow set of ivory tablets, mounted in tarnished gold, and wrote upon them with a pencil in a case of tarnished gold that hung from her neck.

The compact, reusable nature of an ivory notebook would have suited Jefferson down to the ground. Obsessive as he was about his daily observations — his house at Monticello bore a weathervane connected to a compass rose on the ceiling of one of its porticoes, and his pockets were weighed down with gadgets such as a thermometer, a compass, a spirit level and a globe — his ivory polyptych let him take notes with a pencil throughout the day before later copying them onto a more permanent medium.7 His daily routine, in other words, was not so different from that of a literate Greek or Roman. And though it may be stretching the analogy just a bit, if we consider that today many of us make ephemeral notes on our smartphones and (ahem) our tablets before sorting through them at a later time, we too are walking in the footsteps of our ancestors. Writing technologies change over time; people, not so much.

- 1.

-

Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin. “Preface”. In Written on Bamboo & Silk : the Beginnings of Chinese Books & Inscriptions, xxi-xxiv. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- 2.

-

Wilkinson, Endymion Porter. “1. Manuscripts on Bamboo and Wood”. In Chinese History: A Manual, 444-447. Harvard University Asia Center, 2000.

- 3.

-

Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin. “Silk As Writing Material”. In Written on Bamboo & Silk : the Beginnings of Chinese Books & Inscriptions, 126-144. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- 4.

-

Bülow-Jacobsen, Adam. “Writing Materials in the Ancient World”. In The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, edited by Roger Bagnall, 3-29. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- 5.

-

Lewis, Naphtali. “The Manufacturing Process and Its Products”. In Papyrus in Classical Antiquity, 34-69. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974.

- 6.

-

oxforddictionaries.com. “Diptych”. Accessed November 19, 2017.

- 7.

-

monticello.org. “‘I Rise With the Sun’”. Accessed November 19, 2017.

Comment posted by John Cowan on

Note, however, that South Indians had no trouble writing left-to-right on palm leaves (which is why their scripts have very few straight lines; they would crack it) rather than top to bottom.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Interesting! How wide were the leaves? From what I’ve seen and read, the bamboo slips from which scrolls were made were about the same size and shape as two chopsticks placed side by side.

Comment posted by Stephen O. Saxe on

I’m surprised to see that Dickens wrote “mounted in tarnished gold, and wrote upon them with a pencil in a case of tarnished gold that hung from her neck.”

One of the unique qualities of gold is that it does not tarnish.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

And — and! — he uses the expression “tarnished gold” twice in the same sentence. Maybe not his finest hour.

Comment posted by ktschwarz on

Pure gold doesn’t tarnish, but gold is often alloyed with copper or other metals to make it harder, and the alloy can tarnish. Just google “tarnished gold”, plenty of jewelers will advise you on how to clean it. Or the case might have been gold-plated silver, which means the silver can diffuse to the surface and tarnish. Dickens didn’t make a mistake.

Comment posted by Jill on

So interesting! I absolutely love all this stuff and enjoyed both of your books!

All My Best,

Jill

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Thanks! I’m glad you enjoyed the post. I had fun writing it too.

Comment posted by Steve Minniear on

How did one erase the notes on the polyptych? And how was the item constructed so that carrying it (in a pocket?) didn’t allow the writing to be worn off?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Steve — Jefferson used a pencil to write on his ivory tablets and, as such, I presume it must have been easy enough to clean off the graphite with water and perhaps some soap.

Separately, if you take a look at the image of Jefferson’s polyptychs above, you’ll see that their constituent leaves were stacked, drilled, and then fixed together so as to pivot about a single point. When “closed”, the two outermost leaves would protect the writing on the inner leaves from being rubbed off while in a pocket.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by derek on

Jane Austen had one, and is using it as a metaphor when she writes her famous line about her art being inscribed on “two inches of ivory”. It has been pointed out that, like a modern word processor, you can rearrange paragraphs to try out their effect in different orders.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Derek — how interesting! I hadn’t realised the extent to which ivory notebooks were used during the late modern period. I don’t have the figures offhand, but presumably paper was too expensive at that time to be used as a day-to-day note-taking medium. And yes, a stack of ivory slates would have been ideal for arranging and rearranging paragraphs. A neat idea.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by John Williams on

A character in William Faulkner’s novel The Mansion uses one of these. She was rendered deaf during the Spanish Civil War, and because of her toneless voice, uses it to communicate.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John — thanks for the note! I’ve never quite got into Faulkner, but if I ever read The Mansion I’ll keep an eye out for the reference.

Comment posted by ktschwarz on

Benjamin Franklin not only had an ivory notebook, he sold them at his printer’s shop in the 1730s and 40s, according to this article: Benjamin Franklin: Printed Corrections and Erasable Writing, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 150, No. 4 (Dec., 2006), pp. 553-567. Paper was quickly destroyed by repeated erasing, unlike ivory.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

What a great find! Thank for you the reference. One for my reading list.