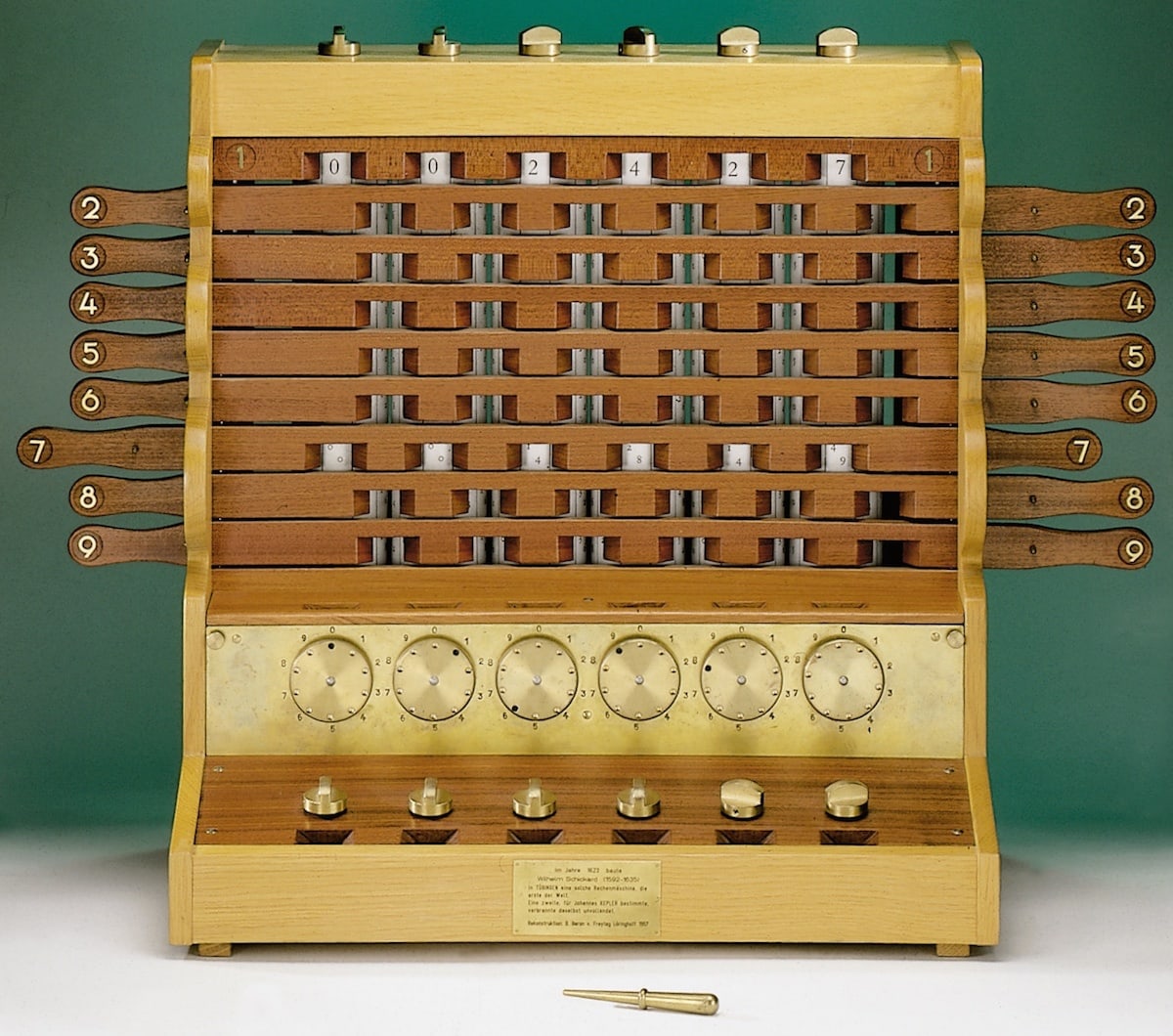

The machine that belatedly claimed the crown of first practical mechanical calculator, after the failure of Wilhelm Schickard’s Rechenuhr and many other pretenders, was this one: the arithmometer designed by Charles Xavier Thomas de Colmar, administrator in Napoleon’s army, insurance pioneer, and Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur.1 It was a long time coming.

As with Napier, Schickard, and others before him, Thomas wanted to reduce the mental labour required in everyday arithmetic. No-one had yet succeeded, as an American publication called The Manufacturer and Builder explained in 1872:

[Some calculators] were so complicated that it would take an engineer to run them, and a watch-maker to keep them in order, while others were evidently designed by men who knew nothing, practically, of the working of machinery […] Finally, every machine was out of order, and gave arithmetical results that would bankrupt the most successful business man in two turns of the handle.2

Thomas, finally, would break the impasse. He worked on the arithmometer for much of his life, obtaining an initial patent in 1820 and then refining his machine on and off for the next fifty years. The result was a robust, sophisticated machine that could add, subtract, carry, and even, with some clever manipulation, multiply and divide — and it could do so over and over again with impressive consistency. It was not cheap, exactly (Henry Brunel, an English engineer, paid the equivalent of almost $2,000 in today’s money for a single arithmometer), but it worked, and it worked well, inaugurating features such as sliders to set inputs, a sliding “carriage” to record the running total, and a crank to enact each addition or subtraction, that would go on to be used in many similar devices.1 The arithmometer was the shape of things to come.*

- 1.

-

Johnston, Stephen. “Making the Arithmometer Count”. Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society, 1997, 12-21.

- 2.

-

The Manufacturer and builder : a practical journal of industrial progress. “Calculating Machine.”

- *

- Ironically, the arithmometer itself would eventually come in a different shape, but we’ll get to that story another time soon. ↢