The ‘#’ symbol is something of a problem child. It seems at first to be quite innocuous, a jack-of-all-trades whose names and uses correspond in a pleasingly systematic manner: ‘#5’ is read ‘number five’, leading to the name ‘number sign’; in North America, ‘5#’ means ‘five pounds in weight’, giving ‘pound sign’, while the cross-hatching suggested by its shape leads to the commonly used British name of ‘hash sign’.1

Dig a little deeper, though, and this glyph reveals itself to be a frustratingly multifaceted beast. Its manifold uses encompass the sublime and the ridiculous in equal measure. Its varied but functional aliases have lately been joined by the grandiose moniker ‘octothorpe’, bestowed upon it for reasons more frivolous than practical, and the whys and wherefores of its etymology elude even the most studied experts. The simple ‘#’ is not nearly as simple as it seems.

Unlike the pilcrow, whose lineage of Greek paragraphos and Latin capitulum can be plainly seen in a succession of ancient manuscripts, and unlike the interrobang, whose creator thoughtfully provided the definitive explanation of its etymology, solid clues to both the ‘#’ symbol’s visual appearance and its various names prove to be thin on the ground. Perhaps the most credible story behind the evolution of the symbol, and the only one to be corroborated by at least some tangible evidence, springs once again from ancient Rome.

The Roman term for a pound in weight was libra pondo, where libra means scales or balances (from which the constellation takes its name)2 and where pondo comes from the verb pendere, to weigh.3 The tautological flavour of this pairing is borne out by the fact that both libra and pondo were also used singly to mean the same thing — a pound in weight4 — and it is from these twin roots that the ‘#’ takes both its form and its oldest name.

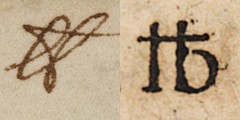

Some time in the late 14th century the abbreviation ‘lb’ for libra entered English,* and according to common scribal practice it was accessorised with a line drawn across the letters to highlight the use of a contraction.6 Jotted down in haste, as can be seen in Isaac Newton’s elegant scrawl below, ‘℔’ was transformed into ‘#’ by the carelessly rushing pens of successive scribes.7 Originally so common that some early typecutters provided a dedicated letter punch for it, but now considerably outshone by both predecessor and descendant, ‘℔’ has become a typographic missing link.†

Parallel to all this, libra’s estranged partner pondo was also changing. Where libra had become ‘lb’ and subsequently ‘#’ through the urgency of the scribe’s pen, pondo was instead subjected to the vagaries of the spoken tongue. The Latin pondo became first the Old English pund, (sharing a common Germanic root with the German Pfund) and subsequently the modern word ‘pound’.9 Libra and pondo were reunited, and ‘#’, the ‘pound sign’, was born.

The ‘#’ is not the only child of the phrase libra pondo, and the ‘£’ symbol for ‘pounds sterling’, the British unit of currency, is one of its more notable siblings. The term originates from the practice of weighing coins to determine the value of a payment,‡ such as might be made in silver Norman pennies called ‘sterling’, while the ‘£’ symbol itself is an abbreviation for libra in the form of a stylised uppercase ‘L’.11 In fact, clues to the ‘£’ symbol’s Latin ancestry remained quite explicit until decimalisation in 1970. In Charlemagne’s system of coinage from the 8th century AD, 240 denarii were minted from one libra of silver, and twelve silver denarii had the same value as one gold solidus.14 This ratio — 240 : 12 : 1 — was retained in Britain until decimalization, and the traditional abbreviation for ‘pounds, shillings and pence’ came straight from the Latin librae, solidi, denarii to yield ‘£sd’, or ‘L.s.d.’.15

Despite boasting Latin roots of noble purpose, the ‘#’ symbol has since come to be used so promiscuously as to be completely dependent on its context. In addition to its uses as pound and number signs, in chess notation a ‘#’ signifies checkmate;16 for the less pedantic typographer it can be a stand-in for the musical sharp symbol (‘♯’),§ and in many programming languages it indicates that the rest of the line is a comment only, not to be interpreted as part of the program.18 Proofreaders wield the ‘#’ to denote the insertion of a space: placed in the margin, an accompanying stroke indicates where a word space should be inserted, while ‘hr #’ specifies that a thin or ‘hair’ space should be used instead.19 Perhaps most obscurely, three hash symbols in a row (‘###’) are used to signal the end of a press release.20

The ‘#’ has names almost as varied as its uses, and aside from the prosaic ‘number’, ‘pound’ or ‘hash’ sign, it is or has been variously known as the ‘crunch’, ‘hex’, ‘flash’, ‘grid’, ‘tic-tac-toe’, ‘pig-pen’ or ‘square’.21,22 In most cases, a name can be trivially linked to the character’s shape or to its function in a particular context, but its most elliptical alias does not give up its secrets so easily. The story of how the ‘#’ symbol came to be known as the ‘octothorpe’ is entirely more tortuous.

Works such as Robert Bringhurst’s Elements of Typographic Style (widely acknowledged as the modern bible of typography), the American Heritage Dictionary and the mighty Oxford English Dictionary have all weighed in with competing explanations for the origins of the ‘#’ mark’s most prominent nickname. The 4th edition of the American Heritage Dictionary, for instance, says this of the word ‘octothorpe’:

- oc·to·thorpe

- n. The symbol (#).

Alteration (influenced by octo–) of earlier octalthorpe, the pound key, probably humorous blend of octal, an eight-point pin used in electronic connections (from the eight points of the symbol) and the name of James Edward Oglethorpe.23

Unfortunately for this particular definition, the AHD appears to be its sole proponent. Oglethorpe, founder of the American state of Georgia as a refuge for inmates of English debtors’ jails,24 seems an unlikely candidate to be granted such an honour; his name is little known outside the state he founded, and there is no real evidence to suggest a link between Oglethorpe’s haven for financial miscreants and the character itself. The AHD provides no details of the provenance of this theory, and it has a strong whiff of speculation about it.

Robert Bringhurst and the OED come closer to agreeing on a plausible theory. The Elements of Typographic Style states that:

In cartography, it is a traditional symbol for village: eight fields around a central square. That is the source of its name. Octothorp means eight fields.25

A picturesque theory, and one with an apparent historical significance: the suffix -thorp(e) is an Old English word for village26 and can still be seen in British place names such as Scunthorpe. However, it is unusual to find a Greek prefix such as octo- wedded to an Old English word in this manner, and indeed the OED’s own definition for octothorpe acknowledges its unconventional construction. It provides two similar but separate etymologies, both of which emanate from the unlikely linguistic wellspring of AT&T’s one-time research subsidiary, Bell Telephone Laboratories. The first cites the industry journal Telecoms Heritage, explaining that an engineer named Don McPherson was hunting for a suitably unique name for the age-old symbol:

His thought process was as follows: There are eight points on the symbol so ‘OCTO’ should be part of the name. We need a few more letters or another syllable to make a noun […] (Don Macpherson […] was active in a group that was trying to get JIM THORPE’s Olympic medals returned from Sweden). The phrase THORPE would be unique[.]27

while the second quotes a 1996 issue of New Scientist magazine, and claims that:28

‘Octo-‘ means eight, and ‘thorp’ was an Old English word for village: apparently the sign was playfully construed as eight fields surrounding a village.29

Though this construction matches Bringhurst’s suggestion, the two disagree on its derivation: Bringhurst claims that the name ‘octothorpe’ is derived from a ‘traditional [cartographic] symbol’, while the OED suggests that it is instead a modern name, a tongue-in-cheek amalgam of Greek and Old English applied to a much older symbol. Unfortunately for Bringhurst, the ‘#’ is not a cartographic symbol; though his construction is correct, his etymology is not.

Of course, the OED’s two suggested etymologies still stand: octo- for eight points plus the name ‘Thorpe’, and octo- for eight fields and thorpe for village, both of which emanate from that most unexpected of sources, Bell Labs. The question remains: why, exactly, did the engineers at America’s premier telecommunications lab feel compelled to give this centuries-old symbol a new name?

- 1.

-

“Hash”. Oxford University Press, April 2011.

- 2.

- Unknown entry ↢

- 3.

- Unknown entry ↢

- 4.

- Unknown entry ↢

- 5.

-

Cappelli, Adriano., David. Heimann, and Richard Kay. “The Elements of Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography”. In. University of Kansas Libraries, 1982.

- 6.

-

Bischoff, Bernhard, and . “Abbreviations”. In Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, 150+. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- 7.

-

Irwin, Keith Gordon. The Romance of Writing from Egyptian Hieroglyphics to Modern Letters, Numbers, & Signs. Viking, 1961.

- 8.

-

“{Unicode Character ’L B BAR SYMBOL’ (U+2114)}”. FileFormat.info, May 7, 2011.

- 9.

-

“Pound”. Oxford University Press, May 2011.

- 10.

-

, and Ernest. Brehaut. Cato the Censor on Farming. Vol. 17. Columbia Univ. Press, 1933.

- 11.

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Pound Sterling (money)”.

- 12.

-

Friedberg, Robert, Arthur L. Friedberg, and Ira S. Friedberg. “Gold Coins of the World : Complete from 600 A.D. to the Present : An Illustrated Standard Catalogue With Valuations”. In Gold Coins of the World : Complete from 600 A.D. to the Present : An Illustrated Standard Catalogue With Valuations. Coin and Currency Institute, 1980.

- 13.

-

Judson, Lewis Van Hagen. Weights and Measures Standards of the United States : A Brief History. Dept. of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, 1976.

- 14.

-

Redish, Angela. “From Carolingian Penny to Classical Gold Standard”. In Bimetallism: An Economic and Historical Analysis, 1-12. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- 15.

-

Sutherland, C. H. V. English Coinage, 600-1900. B.T. Batsford, 1973.

- 16.

-

“E.I.01B. Appendices”. World Chess Federation, April 2011.

- 17.

-

Cullen, Drew. “Why Microsoft Makes a Complete Hash Out of C#”.

- 18.

-

“2. Lexical Analysis”. Python Software Foundation, May 5, 2011.

- 19.

-

Rosendorf, Theodore. “proofreaders’ Marks”. In The Typographic Desk Reference, 67. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2009.

- 20.

-

Yale, David R., and Andrew J. Carothers. The Publicity Handbook : the Inside Scoop from More Than 100 Journalists and PR Pros on How to Get Great Publicity Coverage : In Print, Online, and on the Air. NTC Business Books, 2001.

- 21.

-

Fulford, Robert. “How Twitter Saved the Octothorpe”. National Post.

- 22.

-

“Green Book”. In. International Telecommunication Union, 1973.

- 23.

-

Baugh, John, Robert Hass, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Wendy Lesser. “The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language”. In. Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

- 24.

-

Blackburn, Joyce. James Edward Oglethorpe. Lippincott, 1970.

- 25.

-

Bringhurst, Robert. “Octothorpe”. In The Elements of Typographic Style : Version 3.2, 314+. Hartley and Marks, Publishers, 2008.

- 26.

-

“Thorp”. Oxford University Press, May 2011.

- 27.

-

Carlsen, Ralph. “What the ####?”. Edited by Andrew Emmerson. Telecoms Heritage Journal, no. 28 (1996): 52-53.

- 28.

-

Dekker, Kay. “Letters: Internet Hash”. New Scientist.

- 29.

-

Simpson, J. A., E. S. C. Weiner, and . The Oxford English Dictionary. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1989.

- *

- The corresponding abbreviation ‘oz’, for ‘ounce’, has a similar genesis. The Latin uncia, or twelfth (used in the sense of twelfths of a Roman pound), became the medieval Italian onza and was subsequently abbreviated to ‘oz’.5 ↢

- †

- ‘℔’ does still survive today, lurking unremarked in the standard computer character set Unicode as the so-called ‘L B BAR SYMBOL’.8 It is rare to see it used in type. ↢

- ‡

- Neatly coincidental though all this appears, nailing down the exact weight of a so-called ‘pound’ is remarkably tricky. The Roman libra pondo, for example, was divided into twelve uncia or ounces and weighed approximately 327 grams.10 The ‘pound’ of silver from which the British unit of currency is derived was instead closer to a ‘troy pound’,11 named for the French town of Troyes, and weighed in at roughly 373 grams. Like the libra pondo, the troy pound is divided into twelve ounces, though these ‘troy ounces’ are commensurately heavier than their Roman equivalents.12 Finally, the modern ‘international pound’ — formalised from an older common unit named the avoirdupois pound — comprises sixteen ounces rather than twelve and is defined to be exactly 0.45359237 kilograms.13 Little wonder the metric system is now mandated by law in all countries bar the USA, Liberia and Burma. ↢

- §

- Microsoft took this path of least resistance when rendering the names of their programming languages ‘C Sharp’ and ‘F Sharp’ as ‘C#’ and ‘F#’, attracting a certain amount of derision in the process.17 ↢

Comment posted by Robert Seddon on

Sorry if you’re aware of the bug already, but your URLs are getting erroneous escape characters inserted into them, so _ becomes \_ and # becomes \#.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Robert,

This is caused by a bug I’ve previously reported to http://www.citeulike.org, but nothing has been done about it yet. I should be able to work around it by modifying the citation plug-in I use.

Thanks for the warning, though!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Robert — I’ve added a workaround to remove the spurious ‘\’ characters, and both the URLs and the article titles should now be correct. Let me know if you have any more problems!

Comment posted by John Cowan on

For “Issac” read “Isaac”, and for “descended from” read “cognate with”. The German word is not ancestral to the English one, as apes are not ancestral to humans; rather, both descended from a common ancestor, or in Latin a cognatus.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John,

Thanks for catching these errors! This entry has been the most difficult to write to date, partly because of time pressures and partly because of the inherent unevenness of the subject matter, so I’m grateful for the help in bringing it up to par.

I’ve fixed the spelling mistake and removed the clause about thorpe and Dorf — I must have misread the dictionary definition.

Thanks again, and I hope you enjoyed the rest of the article!

Comment posted by Anthony Osten on

I believe the same goes for Pfund and pound – they both come from the same ancestral word, but the English has not descended from the German, in fact, it probably represents an earlier Germanic spelling.

See here for more information http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_German_consonant_shift

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Anthony — thanks for the notice. I’ll fix that as soon as I can!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Fixed. Thanks again!

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Where you reference “LB Bar Symbol”, #8468, is somehow showing up in my browser as an open spiral glyph. I think this is a function of the font your page is rendered in; when I copy and paste the open spiral to another document I get an LB Bar Symbol. Is it showing up properly in your browser? Is the open spiral an alternate form of the same symbol?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi MK,

Thanks for letting me know! I saw this occur on one Windows PC while writing the entry, but I haven’t been able to reproduce it. You’re almost certainly right about it being a function of the font; even among Windows machines, there seems to be variability in the set of available web-safe fonts, or at least in the character sets they support.

Unfortunately I’m not sure what I can do to fix this problem right now. When time permits, I’m planning to move to downloadable web fonts and I should be able to control the way the text is rendered far more tightly.

Sorry to not be of more help!

Comment posted by Jason Black on

So THAT’S why “lb” stands for “pounds.” Wow. The curiously parallel development of symbol and word is making my head spin, otherwise I’d have something suitably sage to say about it.

And in case it helps, the lb-bar showed up correctly on my machine (also Windows, IE8)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jason — thanks for the comment! The relationship between libra, lb and pound was a surprise to me too, as was the derivation of the ‘#’ symbol. Investigating the octothorpe has been quite an eye-opener.

Comment posted by Emlyn on

And I just realised that’s probably why the slash sign is also called a solidus – it was used to denote shillings in pre-decimal British currency (e.g. 2/-).

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Emlyn — yup, I think you’re right. I came across that derivation too.

Comment posted by Mike on

Emlyn, I don’t believe you are correct on that one. I am exactly as old as Decimal currency, but from what I recall, a price of 2/- would denote two shillings exactly, not two pounds as you seem to be suggesting.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Mike — I think (though I may be wrong) that Emlyn is suggesting that ‘2/-’ stands for ‘two shillings’.

Comment posted by Harry on

That thing about pre-decimal British currency being descended from Carolingian coinage, and l.s.d. standing for librae, solidi, denarii, is fabulous. I can’t believe I didn’t know that. It’s almost as good as the fact that acre, furlong and so on are derived from the size of a medieval ox-plough.

L.s.d. as an abbreviation can lead to confusion for those of us who grew up after decimalisation: I remember reading an old novel which had an exchange which was something like “You know why she married him, don’t you?” “Yes, the L.s.d.”

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Harry –thanks for the comment. I can well imagine that there’s something of a generation gap when it comes to the meaning of L.s.d./LSD…!

Comment posted by Blair Mitchelmore on

I’ve never seen ‘5#’ as a reference to weight in my life. Is there evidence this is still done or is it an artifact of older usages? Or perhaps it possible I’ve never seen it because I’m Canadian and it’s not a North American thing but rather a purely American construction?

Comment posted by Tammela on

I believe physicians often use this as shorthand.

Comment posted by Andrew Perron on

I’ve seen it on a few occasions in grocery store signs.

Comment posted by John on

I’ve spent nearly 60 years in the US and have never seen # used to denote weight.

Comment posted by Tim Dixon on

Thanks for this series, Keith. Tremendous work, and fascinating reading. I hate to add to your already lengthy to-do list, but the paragraph just before the second *** appears to have a misspelling – “octothope”. I’m looking forward to part 2, and to more articles in the series. Thanks again!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Tim,

Thanks for pointing that out — it should be fixed now. I’m glad you’re enjoying the site!

Comment posted by Leonardo Boiko on

The part about “octothorpe” being an obscure name reminded me of the haček diacritic (an inverted circumflex, ̌, used in Finnish, Chinese pīnyīn & others). In Unicode that symbol is called a “caron”, a mysterious name inherited from elder technical standards. The Unicode FAQ has this lovely answer to the question of why it has that name:

(They go into a little more detail so check it out.)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

And even the OED is stumped? Intriguing stuff.

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Is the diacritic used for tone 3 in Pinyin the same as a haček? I thought the tone 3 marker was rounded and the haček angled.

Comment posted by Leonardo Boiko on

According to Wikipedia, the tone 3 marker is supposed to be angled—with fits in nicely with a long tradition (dating at least from neume musical notation, I think) of composing several acute and grave symbols together to denote changes in pitch (the circumflex also started this way). Apparently the pīnyīn diacritic is derived from zhùyīn/bopomofo, but the bopomofo mark is angled, too.

Wikipedia also says the reason one sometimes see a rounded tone mark is simply due to technical limitations (in my experience, at least, the haček vowels are still one of the least common glyphs to be included in Latin fonts). The rounded haček-like mark is called a breve (“brief”), from the old tradition of explicitly annotating Latin syllables as short or long (the latter being marked with macrons: ă vs. ā).

This situation where a technical limitation can be mistaken for a standard also happens with pīnyīn “a”. Many people think it’s supposed to always be a “single-storey a”, even in roman, and even though in most Latin fonts single-storey is only used for italics. The truth is that early computers simply didn’t had a glyph like a double-storey “ǎ”, and substituted a single-storey; there’s nothing in pīnyīn mandating it.

Comment posted by Nicholas on

Spelling correction:

Just before the second “****”:

“The story of how the ‘#’ symbol came to be known as the ‘octothope’ is entirely more tortuous.”

I think you meant ‘octotho/r/pe’.

Keep up the good work!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Nicolas — that should be fixed now. Thanks!

Comment posted by Jason Black on

P.S. A quick peek at Google ngrams definite supports the notion of a late ’60s genesis for the name:

http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/graph?content=octothorpe&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=0&smoothing=3

However, comparing “octothorpe” with more pedestrian names such as “pound sign” definitely suggests that “octothorpe” is by far the minority appelation for the sign:

http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/graph?content=octothorpe%2C+pound+sign&year_start=1800&year_end=2000&corpus=0&smoothing=3

As such, I have to wonder whether that can in any meaningful way be considered the “true name” of the #.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Richard,

Nice use of Google Ngrams! I’d agree that ‘octothorpe’ isn’t the “true name” of the symbol, but despite this, it seems to soldier on even now. In that sense it’s a bit like the interrobang — seemingly here to stay, even if perpetually flying just under the radar.

Comment posted by Brian Fenton on

Whether canonical or not, I think octothorpe is the most fun to say, so the name may stick around longer for that reason.

As a coder, #! is also used as an interpreter instruction in scripting files, and it can go by shebang, hash bang, or crunch bang (which is also the name of a Linux distribution).

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Brian — very true. The problem with having such switched-on commenters is that all my best material is published before I get round to it myself…!

Comment posted by pageturners on

Aged sub-editors used to call this mark a ‘half-double’ when I was training in my art.

Comment posted by Jane Nesmith on

I love your site and the research you’re doing! I may have my students read it (a new class: grammar, style, and editing–I think typography can go in it!)

I have a request. Although I like your site, I find it hard to read. I think it’s because of the leading. Could you reduce the space between the lines? There must be a reason it’s hard to read a “double-spaced” essay on screen! Maybe one of your erudite readers can comment on this.

Thanks for your stories.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jane,

The typography here seems to be a polarising subject! I understand that the font is quite large and the leading on the…generous side, but I find myself going back and forth on whether or not to change them.

Changing the leading might be less controversial than the font size itself, so I may experiment sometime between articles. I can’t promise to put a date on it (mostly because the deadlines I set for myself, other than those for the articles themselves, go chronically unmet), but I’ll see what I can do.

Thanks for the comment, and I’m glad you’re enjoying the site!

Comment posted by Andrew Perron on

Personally, I like it. I find it easy to read, and it adds an air of easy dignity.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Good to hear it! Like I said, the typography here is a divisive subject.

Comment posted by Pete Green on

I’d like to add a word in praise of the typography on the site too. There aren’t many other websites I find it so easy to stick at and keep reading – although the fascinating content here must help a bit on that score too!

Comment posted by Dan Visel on

Unfortunately for Bringhurst, the ‘#’ is not a cartographic symbol; though his construction is correct, his etymology is not.

Is the symbol for the command key on the Mac related to the octothorp? (I like Bringhurst’s more parsimonious spelling more than with the “e,” but I grew up on Bringhurst.) The command sign is of cartographic origin; it also looks a great deal like an octothorp, though that might be coincidence.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Dan,

Thanks for the comment!

I’m not sure about the glyph on the command key, although I do notice that Urban Dictionary calls it an ‘extruded octothorpe’. Something to look at in the future, perhaps.

Comment posted by Adam Rice on

The story on the command-key symbol from folklore.org

Comment posted by spicefaerie on

what about it’s usage on Twitter? #ordoespopularculturenotcounthere? :D lovely article! I very much enjoyed it.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

#notatall! In fact, Nimble Books tweeted about this post and added a rather amusing tautological hashtag:

Also, I’ll be talking a bit about Twitter and the octothorpe/hash in the second article.

I’m glad you’re enjoying the site!

Comment posted by antiphrast on

The glyph on the command key is, of course, a ‘hannunvaakuna’.

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

From the Google “translation” of the Finnish wiki page it looks like that means “St. John’s Coat of Arms” — is that right?

Comment posted by antiphrast on

Yes. Here’s a link to Wikipedia’s page on ‘Saint John’s Arms’. I just like ‘hannunvaakuna’ better.

Comment posted by Mark on

There are related humorous terms for the equals sign = a.k.a. the quadrathorpe, and even the humble hypen/minus – as the bithorpe. Obviously, they were derived from the octothorpe, and used mainly for amusement.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Mark — great stuff! I like the idea of a ‘unithorpe’ for a point, or a ‘zerothorpe’ for a space.

Comment posted by Steve Liversidge on

So, “negathorpe” would be a back space, then?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Steve,

As a recovering engineer, I’d say that a backspace would have to be a “negative n-thorpe,” where n is the thorpe-arity of the character to be deleted.

Alternatively, “negathorpe” is good.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Mark Etherton on

Language Log had a discussion about the use of the term ‘pound sign’ for the octothorpe here: http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=2461

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Mark — some nice references in there. Thanks for the link!

Comment posted by Boyd Adamson on

So, any clue as to the origin of the symbol’s use as the number sign?

Re the command key, Andy Hetzfeld tells the story of it coming from a symbol dictionary and meaning an interesting feature in a Swedish campground. It’s at folklore.org but my phone won’t let me paste the URL.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Boyd,

I’m afraid I haven’t come across any particularly helpful evidence about ‘#’ as used as a number sign. You’re quite right about the use of ‘⌘’ for interesting features — it’s used in various countries across Europe for this purpose.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by John F on

This is purely my speculation, but I like to think C# is the natural progression from C++, which was the natural progression from C, where ++ is the increment operator.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John,

Wikipedia suggests that the musical meaning of “a semitone higher in pitch” was intended to mimic C++’s use of the ++ operator. I’d always thought that it was a bit of a typographic pun, with two ‘+’ symbols overlaid to form the sharp.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Dave O'Flynn on

Minor erratum:

The first mention of the word interrobang is linked to http://www.shadycharacters.co.uk/tag/pilcrow instead of http://www.shadycharacters.co.uk/tag/interrobang/

I’m really enjoying the series; keep it up.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Dave — thanks for pointing that out. I’m glad you’re enjoying the site!

Comment posted by Rainer Brockerhoff on

Thanks for the excellent articles. One minor comment regarding “octal, an eight-point pin used in electronic connections”: the term usually refers to a type of socket used by 8-pin vacuum tubes (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tube_socket#Octal); sometimes the socket was also used for relays. I do remember having an unused cable connector for such a socket, but never saw it in an actual product.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ranier,

Thanks for the clarification! I’m quoting directly from the American Heritage Dictionary here, and it’s entirely possible that their definition is a little off.

Comment posted by Jared on

Would love to read more about Flat, Natural, and Sharp and how those characters arose in musical typography:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accidental_(music)

Keep up the great work.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jared — a colleague of mine also happened to mention music typography recently. I’ll have to look into it!

Thanks for the comment.

Comment posted by Bruce Holtgren on

Fantastic entry. I really had no idea.

Comment posted by Shannon on

Thanks for the interesting and well-researched article. Is there any chance you have a citation for the # not being a cartographic symbol? My research only gives me dozens of sites saying it is (almost all of them quoting Bringhurst, all of them etymology rather than cartography sites), but yours is the only article that disputes that. I can’t find any evidence from the cartography side of the debate anywhere, and I’d like to know more.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Shannon,

I couldn’t find any sources to verify the supposed cartographic origins of the symbol, though that isn’t to say they aren’t out there. I go into this in a little more detail in the book — if you can hang on until autumn next year, I’ll have a little more for you then!

Thanks for the comment.

Comment posted by Bertil on

The # is used a cartographic symbol in Sweden (at least) for sawmills, or more precisely, as a symbol for the part of the mill where the planks are stored for air-drying.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Bertil — that’s intriguing! I haven’t come across that before. Do you have any pointers to documentation about it? I’d love to feature this on Shady Characters.

Comment posted by Bertil on

Hi Keith,

I may have the symbol in the legend to some of my maps from the 1980s, but I found this pdf about symbols in Swedish nautical charts (!). The symbol, “brädgård” in Swedish, is in the bottom right corner of page 1, http://lazy.lindvall.eu/pdf/Korta_som_webben.pdf

The # symbol is sometimes called “brädgård” in Swedish, but not so much nowadays.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Bertil — that’s great! Thanks for looking that out. If you’re amenable, I may put together a short post about this cartographic use of the ‘#’ symbol.

Comment posted by Bertil on

Hi Keith,

I’m only happy if this can be of any use to you!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

It is indeed. This is the first confirmed use of the ‘#’ (or something very like it) as a cartographic symbol, and it’s used in a quite unusual way. It’ll be great to be able to post about it. Again, thank you very much!

Comment posted by Martina on

Hi,

in my profession (medicine) we use the hash symbol to indicate fractures.

Enjoying the archaeology here!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Martina – thanks for the comment! Glad you’re enjoying the blog.

Comment posted by jimmy midnight on

What fascinating information this all is, both book and comments. My personal interest in this centers on the apostrophe, and way it symbolizes all sorts of contractions. Feel compelled to add that I find the typeface/style remarkably easy to read.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jimmy — I’m glad you’re enjoying the book and the website. I’m very grateful to have so many erudite commenters!

Comment posted by Terry Walsh on

“The tautological flavor of this pairing is borne out by the fact that both ‘libra’ and ‘pondo’ were also used singly to mean the same thing — a pound in weight[4] — and it is from these twin roots that the ‘#’ takes both its form and its oldest name.”

Not quite tautological. ‘pondo’ suggests weight certainly, but libra does not. Its first meaning is ‘scales’. ‘Libra’ may have been referred to as ‘pound’, as this was the unit on which all weights were measured. ‘pondo’ was added to make it clear that it was specifically a measurement of weight.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Terry — thanks for the comment. I meant “tautological” in the sense that both words refer to or imply the act of weighing. I hope that I haven’t confused matters by doing so!

Comment posted by Peter French on

Decimalisation in the UK took place on 15 February 1971, not in 1970. I was in my first year at secondary school, and my 1/6d bus fare for the four-mile journey became 7½p.