The trip from the tourist town of Sorrento, clinging to the cliffs on the southern edge of the Bay of Naples, to the ancient settlement of Pompeii is an engaging one. Sorrento is the end of line, literally speaking: the railway track comes to an end there and so there is often a ticking, cooling train waiting on which to grab a seat before the journey begins. It’s also the place where the line’s itinerant folk bands take a cigarette break before the train beeps to signal its imminent departure. You will put a euro or two into their proffered caps, mostly because the weather is sunny and warm and you’re about to visit one of the most important archaeological sites in Europe, but also because it is physiologically impossible not to tap your foot along with upbeat accordion music.

Two kinds of trains ply the Circumvesuviana line. The new kind, the boring kind, are sleek, air-conditioned commuter appliances indistinguishable from modern light rail systems anywhere in the world, with tinted windows and space-efficient standing-room-only layouts. Their blunt, slab-sided predecessors are far more characterful, like ’70s NYC subway carriages writ large. They are battered, they creak, they are full of sharp edges and exposed rivets and peeling advertisements — and their aluminium skins are covered by graffiti from platform to roof.

Eventually, far later than advertised, the train pulls out slowly. It passes gingerly through the mountain tunnels and across the viaducts that together even out the peaks and troughs of the ragged coastline, and from its windows you watch shipyards, farms, towns and derelict factories pass you by, with the Bay of Naples sparkling behind everything to the west. And with the exception of the plants in the fields (who in their right mind would try to spray-paint crops?), everything is covered with graffiti: the trains, the buildings, the street furniture and all. I was surprised at the scale of it, but then perhaps I shouldn’t have been — the Romans have been graffiti enthusiasts from the dawn of the Republic all the way down to the present day.1

Personally, I was interested in one particular piece of graffiti. Pompeii is the closest that the ampersand has to a place of birth — the earliest recorded ampersand was found there as part of a graffito — and I wanted to find it for myself. I had no idea where in Pompeii it was, but then, I thought, how hard could it be to find? Time has a way of flattening ancient settlements, and I’m used to archaeological sites being mostly horizontal places where buildings, streets, and walls are witnessed only by their outlines in the ground. Surely a piece of graffiti on an upstanding wall would be signposted for all to see?

Well, no.

Pompeii is huge, and it is arrestingly intact. It is 170 acres of ash-blasted homes, shops, cafés, bath-houses, and brothels, all with their stuccoed brick walls still upright,2 with a few marbled temples and stone theatres thrown in for good measure. Imagine all of that enticing wall space in an era before street lighting and you have a graffiti artist’s dream: when Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD,3 choking Pompeii and its inhabitants with a dense cloud of volcanic ash, its walls were covered in messages.

Professor Brian Harvey of Kent State University has compiled a few of the more notable tags, and my word, the Romans were a bawdy lot:4

- Atrium of the House of Pinarius

- If anyone does not believe in Venus, they should gaze at my girlfriend.

- Bar/Brothel of Innulus and Papilio

- Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men’s behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!

- Gladiator barracks

- Floronius, privileged soldier of the 7th legion, was here. The women did not know of his presence. Only six women came to know, too few for such a stallion.

- Peristyle of the Tavern of Verecundus

- Restitutus says: “Restituta, take off your tunic, please, and show us your hairy privates”.

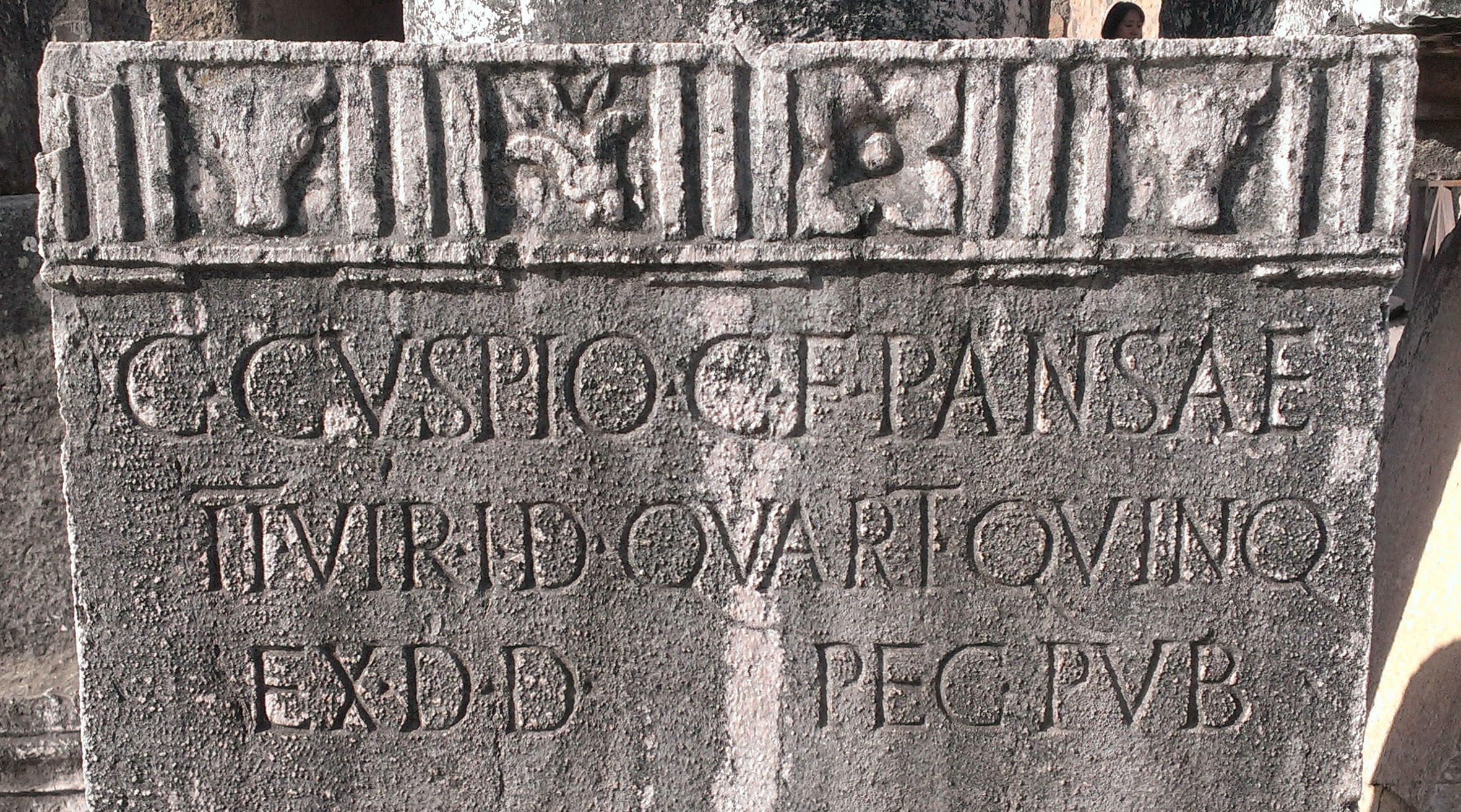

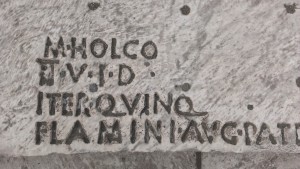

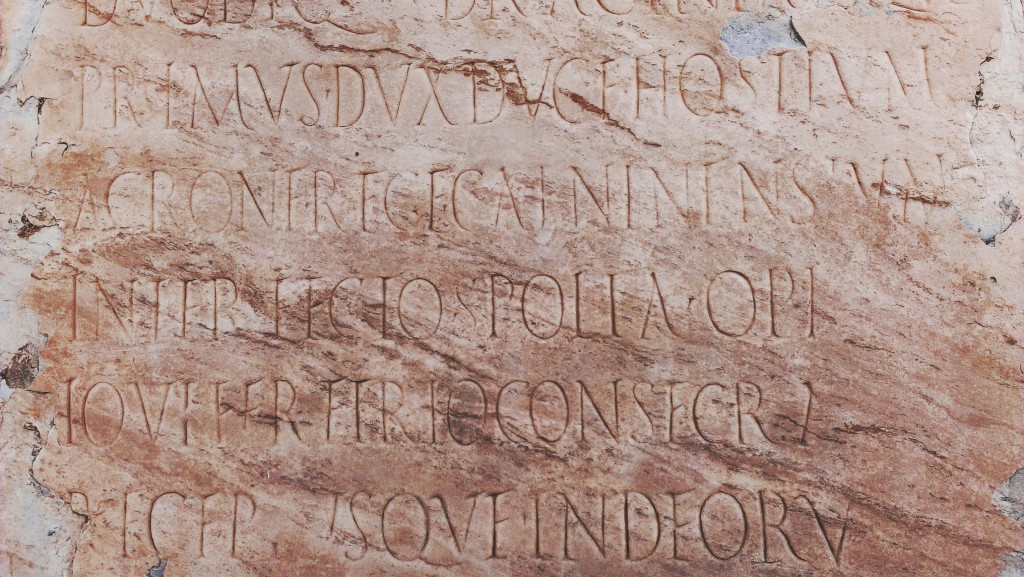

Sadly, much of the graffiti is now lost or illegible, and as much as I looked I could not find anything resembling an ampersand. But there was plenty of “official” writing to take in as we wandered the streets in the baking heat, from monumental inscriptions down to bricks stamped with their maker’s mark, and so here I’ve collected a few of the more interesting inscriptions. (I must apologise for the quality of the photographs; I only had my smartphone with me, and I’ve had to edit some images to bring out the text.)

In the end, I rather forgot about finding the Pompeii ampersand. The sheer variety of messages, scripts and contexts was intriguing: there were monumental inscriptions in stately roman capitals; functional theatre seat numbers in a simple sans serif (brickmakers’ marks used a wonky, flared sans, a kind of fat, drunk Optima); and shopfronts and miscellaneous inscriptions were rendered in homely rustic capitals.

In gawking at all this I almost missed the one thing that should have been evident from the start: there is almost no punctuation! The Romans of the first century AD were still very much in thrall to the scriptio continua of their Greek cousins, and the only commonly-used mark was the interpunct (·), placed between words to it easier to parse continuous texts. There are no commas, colons, or periods here, much less any more sophisticated marks; it makes for a bracingly pure reading experience, if nothing else.

The more I think about it, though, now I’m back in dreich Edinburgh, the more obvious it seems that today’s monuments and shopfronts are lightly punctuated, too. As I look out of the window of the coffee shop in which I’m writing I can see only three non-alphabetic marks: an ampersand (irony!) on a sign for “Property Sales & Lettings”; a pair of “dumb” quotes explaining that a hairdresser is “Open Sundays”; and a full stop in a street sign that reads “St. Stephen Street”. Public typography will tell you a certain amount about how a society wrote their texts and communicated their ideas, but to really understand them you have to look at their more mundane works — the papyrus scrolls thrown onto the refuse heap, the pottery sherds used as makeshift receipts or ballot papers, or the wax tablets on which shopping lists and to-do notes were jotted down. And so today, Pompeii’s punctuational shady characters are little in evidence in the town itself — except, of course, for that one elusive ampersand, scratched somewhere on a wall and patiently awaiting rediscovery.

You can see more photographs of lettering at Pompeii in this photo album at Google Photos. And if you’ve enjoyed this post, why not purchase a copy of the Shady Characters book to learn more about Roman ampersands, lettering and punctuation?

- 1.

-

Ruggeri, Amanda. “Why, Why, Why Does Rome Have So Much Graffiti? - Revealed Rome”. Revealed Rome.

- 2.

-

Art Images for College Teaching. “Pompeii, Construction Detail: ‘faux marble’ Column of Brick Covered With Stucco”. Accessed November 7, 2014.

- 3.

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Vesuvius (volcano, Italy)”.

- 4.

-

Harvey, Brian. “Graffiti from Pompeii”. Pompeiana.org. Accessed November 7, 2014.

Comment posted by John Cowan on

like NYC subway carriages writ large. They are battered, they creak, they are full of sharp edges and exposed rivets and peeling advertisements — and their aluminium skins are covered by graffiti from platform to roof.

Hmp. NYC subway cars in the 1970s, maybe.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John — the first and only time I used the NYC subway was in 2013, and even then I remember it being a little more challenging than, say, the London Underground. But: fair enough. I’ve amended the post accordingly. Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Lorraine Gehring on

This doesn’t have anything to do with Pompeii, but I saw a medieval document online that had a variety of punctuation, including something that looks like a bulls-eye target. Check out pages 8-10 (the bulls-eye is on 10): http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/fs1/object/display/bsb10172852_00011.html

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

Looking at the context (with my feeble Latin), it is just the astronomers´ sign for the sun. The preceding sentences seem to be some astrological jibber-jabber, mentioning Solis, the sun. Symbols for the planets are found in their places. The astronomical signs seem to have been put in service in place of pilcrows.

Comment posted by Lorraine Gehring on

Turns out I was wrong — the bulls-eye and other symbols have to do with reading palms — page 6 shows the symbols on a palm. Still a bit interesting for a 1510 printed book, considering the difficulties of printing odd characters.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Lorraine — that’s a nice find. I suppose the printer could have gotten away with buying in the bulk of their type and then having the few card-specific characters custom-made. But yes, it’s certainly unexpected.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Korhomme on

Not much punctuation in the streets? You only have to search for the greengrocer’s latest offer on lettuce’s, or apple’s.

And not just the grocer’s; the aberrant apostrophe is frequently found elsewhere.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Korhomme — ha! Very true. Even so, public punctuation is usually of a very limited scope (and even more so when you’re only considering the view from one solitary café window, as I did). Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Ned Brooks on

That “LOLLIUM” could just as well be “IOLLIUM” or “TOLLIUM” as the upper part of the first letter is lost. IOLLIUM is found by Google but seems to be an OCR error for TOLLIUM, which seems to be a name.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ned,

I’ve since come across a site suggesting that it is in fact “lollium”. The small letters between the large ones are apparently abbreviations. The entire sign is thought to read: “Lollium d(ignum) v(iis) a(edibus) s(acris) p(ublicis) o(ro) v(os) f(aciatis)”. Google Translate renders this as “Lolli worthy ways of building public and pray you do”, which is not entirely helpful.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Pedar Foss on

Fascinating website, Keith; I used insights from it when teaching Pliny the Younger’s letters about the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius yesterday in Latin class (we were reading the 9th-c. Medici manuscript). Thank you!

Re: Lollius, the translation would be: “I urge that you [referring to any passersby] make Lollius responsible for public streets/buildings/sanctuaries.” In other words, “Vote for Lollius for aedile”; ‘aedile’ was like a city commissioner, an important step in one’s political career. The Lolli were a family descended from local central Italic (originally non-Roman) tribes, and were heavily involved in trade. Several members of the family campaigned for aedile. We don’t know if any of them succeeded.

Let me dredge through my sources and see if I can find the Pompeian address of the ‘et’/’&’ graffito that you were looking for, though the elision of e + t in Roman script at first thought seems to me to have been pretty common at the site. Cheers.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Pedar,

I’m very glad that the website has been of some use! I’m intrigued as to how you worked material from it into your teaching. (Incidentally, the volcanic demise of Pliny the Elder is mentioned in passing in my next book.)

Your translation chimes with a few other sources I found later about the same graffito. It’s striking to see graffiti used in a pseudo-official capacity like this — very different to how it’s regarded today. From the looks of this example, it was closer to professional sign-writing than furtive vandalism.

And lastly, it would be fantastic if you were turn up any more information about et-ligatures at Pompeii. Jan Tschichold only ever reproduced the one proto-ampersand, and it’d be quite an addition to the subject to be able to publish a few more.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by James Lin on

Now that Google+ is going away, will you put your album somewhere else?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi James — I’ll have to! Thanks for the note. I’ll update this post once the album is available elsewhere.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi James – I’ve now moved the album to Google Photos.