Ironics notwithstanding, the irony mark lay dormant for much of the latter part of the 20th century. As had been the case with many other previously obscure marks of punctuation, however, the click-to-publish ease of the web well and truly resusitated its fortunes: more new irony marks appeared in the decade from 2001 to 2010 than in any period before.

Ironically enough, the first digital irony mark was not intended to punctuate irony in a general sense but instead its laser-guided offspring, sarcasm.1 Observing that written sarcasm was chronically misinterpreted as sincerity in online interactions, the blogger Tara Liloia posted an article in 2001 that purported to solve the problem. In “The Sarcasm Mark”, she wrote that:

What I am proposing is a punctuation mark that clears up all confusion about sarcastic remarks for the reader. The closest thing to a sarcasm mark is the winking smiley—and he isn’t really a professional tool. You can’t write a missive to a business associate with little cutesy ASCII faces in it. It’s just not done. […] My solution is the tilde. ~2

As Liloia explained, the closest thing at that point to an irony or sarcasm mark was the “winking smiley” — ;-) — an ‘emoticon’, or combination of ASCII characters* that suggest a particular facial expression. Emoticons had been part of internet language since the days of the ARPANET,† when a joke about a fake mercury spill posted to a Carnegie Mellon University digital message board had been mistaken for a genuine safety warning. The denizens of the message board cast about for a means to distinguish humorous posts from more serious content, and the happy- and sad-face smileys — :-) and :-( respectively — were the enduring result.4 Though common in online communication, smileys carried an inherent informality that excluded them from use as proper punctuation.

Liloia’s proposal, to employ the tilde as a ‘professional’ alternative to the winking smiley, was notable for its convenience. In contrast to Hervé Bazin’s psi-like creation, which had to be specially cut for Plumons l’oiseau, the tilde was common to most typefaces and hence could be typeset without difficulty. Also, unlike John Wilkins’ inverted exclamation point and Alcanter de Brahm’s reversed question mark, it was readily found and typed on most standard keyboards. Liloia explained that in its new role as a sarcasm mark, the tilde was to be used at the end of a sentence:

Why, The Onion [a satirical university newspaper] alone would use hundreds of sarcasm marks each day. Man, the Onion is one great newspaper~ Did you catch that? It was a test sarcasm mark—it worked, didn’t it? You knew I was being sarcastic.2

The tilde as sarcasm mark did find some limited use in instant messaging (though it also has a variety of alternative, contradictory meanings in this context5), but perhaps the most important aspect of Liloia’s article was that it articulated a need — seemingly peculiar to the Internet — to demarcate and regulate sarcasm. Whereas literary authors and journalists had once sought to clarify the use of irony, the rapid-fire, anonymous discourse of the Internet inevitably crystallised that irony into outright sarcasm.‡

Given Liloia’s nod to The Onion, it seems appropriate that the next call for a dedicated sarcasm mark came from a former Onion contributor. In a 2004 article penned for the online magazine Slate, Josh Greenman wrote:

The English language must evolve. Not with emoticons or lol or brb or l8r or GRATUITOUS all caps used for emphasis, not with Spanglish or bumbling Bushisms or even cryptic Kerryisms. We don’t need more quotation marks that “hedge” or try to make the same “old” thing sound “fresh.” What we need is an honest effort to incorporate the way we live today. My fellow Americans, we need to embrace a new punctuation mark–one that embraces the irony and edge of contemporary conversation and clarifies rather than condenses or confuses.

It is time for the adoption of the sarcasm point.7

Through his work for the relentlessly sarcastic Onion, Greenman surely had greater experience than most of the “irony and edge of contemporary conversation”. His article was a polemical call to arms displaying the same fervour and enthusiasm found in Martin Speckter’s interrobang manifesto of thirty-six years earlier8 — shot through, of course, with the rich vein of irony that had become de rigeur in irony and sarcasm mark proposals. The title of his article, boldly showing off his newly minted ‘sarcasm point’, said it all: “A Giant Step Forward for Punctuation¡”

Though Greenman’s essay was intended as a commentary on the culture of the day rather than a genuine attempt to introduce a new mark of punctuation, his choice of the inverted exclamation mark was a neat touch, designed to signal a reversal of the sincerity implied by its normally-orientated counterpart.9 The inverted exclamation point as irony mark exerted a strong pull: Greenman’s use of this glyph mirrored not only John Wilkins’ 17th century effort but also another contemporary use of ‘¡’ to signal sarcasm.

Five years before Greenman’s article, a group of academics presented a paper to the 15th International Unicode Conference in San Jose, California, with the informative but turgid title “A Roadmap to the Extension of the Ethiopic Writing System Standard Under Unicode and ISO-10646”. Unicode is the de facto successor to ASCII, defining more than 109,000 characters taken from over 90 scripts, ancient and modern alike, including Latin, Arabic, Greek, Cyrillic, Japanese, Chinese, cuneiform and many more.10 For a character to be included in Unicode is to have its mainstream use acknowledged,§ and so Asteraye Tsigie, Daniel Yacob et al sought to have a number of Ethiopian colloquialisms codified within this globally accepted standard. Documenting the use of one such character, they wrote:

- Ethiopian Sarcasm Mark “Temherte Slaq”

- Graphically indistinguishable from U+00A1|| (¡) Temherte Slaq differs in semantic use in Ethiopia. Temherte Slaq will come at the end of a sentence (vs at the beginning in Spanish use) and is used to indicate an unreal phrase, often sarcastical in editorial cartoons. Temherte Slaq is also important in children’s literature and in poetic use.11

Evidently, the imperative to punctuate irony and sarcasm does not respect linguistic boundaries.

The coincidence here is striking: three separate uses of ‘¡’ to notify the reader of irony in two different languages and spanning four centuries. Josh Greenman claims never to have encountered either the temherte slaq or John Wilkin’s irony mark,9 but there is clearly an attraction to appropriating existing marks of punctuation, and, subject to some mild tweaking of meaning or appearance, using them in entirely new contexts. This can also be seen in the reversed (and lightly modified) question marks proposed by Henry Denham and Alcanter de Brahm. Despite the cosy familiarity of the marks that result from this particular method of creation, none of them have yet succeeded. The tilde and inverted exclamation point join the long list of irony marks championed by one writer and roundly ignored by all the rest, and the temherte slaq forlornly awaits the Unicode Consortium’s seal of approval.

As if acknowledging the pitfalls inherent in suggesting any new mark of punctuation, the typographer Choz Cunningham hedged his bets when putting forward his own proposal in 2006. His so-called ‘snark’ could be used to imply sarcasm or irony, was composed of two easily-typed, standard characters, and embraced and extended an existing sarcasm mark for good measure.

Just as Martin Speckter had stewarded the creation of the interrobang through a dialogue with the readers of Type Talks magazine, the snark came about after a similarly collaborative design process: the online community at typophile.com hosted a lively debate covering all aspects of the character, from the history and usage of irony and sarcasm marks to putative designs of the new mark.12 As Cunningham’s dedicated website (thesnark.org) describes,

The most eloquent solution was the tilde. Sitting there, dormant since the 1960s, it has lacked a popular or mainstream purpose despite being included on virtually all computer keyboards. Tara Liloia, an early blogger, proposed making sarcasm clearer by ending a sentence with it. […] The classic irony mark and the sarcasm tilde were merged. Plain and stylized forms were explored. The Snark was born!13

And giving an example, he wrote:

A snark is very simple. At the end of the sentence where you want to finish with the mark, add a ~ (tilde) after the . (period).14

As well as the simple pairing of a full stop and a tilde (‘.~’), Cunningham described an alternative form for the snark where the two characters were kerned more closely to yield a single glyph (‘.~ ’).

Unfortunately, as easy as it is to publish a blog entry, post on a forum, or create a website, it is no easier to successfully promote a new mark of punctuation on the Internet than it was during the days of newsprint and hot metal type, and the snark was no exception. If anything, the thoroughness of Cunningham’s promotional efforts belied the difference between the snark and its predecessors: in place of the arch humour that had distinguished Liloia and Greenman’s short, sharp articles, thesnark.org was comprehensive and deadpan. After a first flush of enthusiasm, thesnark.org sank into that limbo specific to abandoned websites, where the ever-receding date on each page counts the months and years since its last update.¶

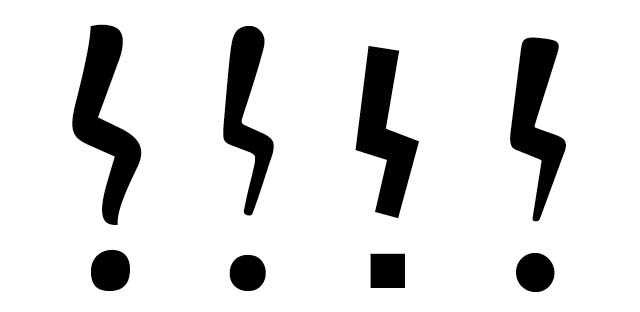

Hot on the heels of Cunningham’s snark came yet another new glyph, this time taking a detour from the solely digital nature of its contemporaries. The symbol designed by the Dutch type foundry Underware was a return to type in more ways than one: it denoted irony rather than sarcasm; it was rooted in traditional literary culture in the same way as Alcanter de Brahm and Hervé Bazin; and it embraced the throw-away nature of previous marks such as Josh Greenman’s sarcasm point.

Each year the Boekenbal, the gala opening of the Netherlands’ annual book festival, has a particular theme. In March 2007 the theme was ‘In Praise of Folly — Jest, Irony and Satire’,15 and that year saw the unveiling of Underware’s ironieteken, a zig-zag exclamation mark specially commissioned to mark the occasion:

Despite the implicitly disposable nature of the mark, intended as it was solely to publicise that year’s Boekenbal, Underware’s Bas Jacobs took his commission seriously. His simple adaptation of the exclamation mark was designed to be easily written by hand, and he considered that:

A simple form is essential to give it a chance to be a success, in contradiction to the interrobang for example. And it has to look like it always existed, not too constructed or rational, but similar like existing punctuation marks.15

Jacobs’ understated ironieteken was launched in a blaze of publicity: presented at the Boekenbal by the Minister of Culture to a packed house of prominent Dutch authors, the following day it featured in a full-page advertisement in the national newspaper NRC Handelsblad. Underware made the mark freely available by adding it to a number of fonts available for download through their website. As a result, the mark attracted a great deal of comment16 and might even have gained wider notice had not some commentators noted that two ironieteken placed in a row bore an unfortunate resemblance to the insignia of the infamous Nazi SS.17 As it was, the ripples caused by the ironieteken within the Dutch literary sphere did not travel far outside it, and thus far the mark remains largely a typographic curio.

When even a seasoned type foundry like Underware can fall foul of such unintended consequences, it might be concluded that attempting to design a credible irony or sarcasm mark is not for the typographically inexperienced. This did not deter the father and son team of Paul and Douglas J. Sak, of Shelby Township, Michigan — respectively an engineer and an accountant18 by trade — from not only designing a new sarcasm mark but also patenting its design and charging for the privilege of using it.

Launched in January 2010, the case for the ‘SarcMark’, as the Saks called it, was couched in much the same terms as previous marks:

With the spoken word, we use our tone, inflection and volume to question, exclaim and convey our feelings. The written word has question marks and exclamation points to document those thoughts, BUT sarcasm has NOTHING! In today’s world with increasing commentary, debate and rhetoric, what better time could there be than NOW, to ensure that no sarcastic message, comment or opinion is left behind[.] Equal Rights for Sarcasm – Use the SarcMark19

Resembling an ‘@’ or a ‘6’ with a point in the middle, the SarcMark was intended to be of roughly similar dimensions to existing glyphs, and included a point because of its presence in other terminal punctuation marks20 such as ‘!’, ‘?’ and ‘.’. It was, like Underware’s ironieteken, made available for download in a digital font; unlike Underware’s mark, though, this font came at a price. $1.99 bought the right to use the SarcMark for non-commercial purposes, with business users directed to contact the Saks directly.

It is safe to say that the creators and supporters of other irony and sarcasm marks were not amused. Or perhaps they were.

Initial news reports of the character’s creation were respectfully factual (“Sarcasm punctuation mark aims to put an end to email confusion” said The Daily Telegraph;21 “Hitting the mark with sarcasm” wrote The Toronto Star18), but as the mark became more widely reported, the cynics waded in with fists flying. Almost every aspect of the SarcMark succeeded in riling one commentator or another. Its visual design was flawed, as the gadget and electronics website Gizmodo Australia opined in an article that started as it meant to go on:

- SarcMark: For When You’re Not Smart Enough To Express Sarcasm Online

- […] For $US1.99 you get to download the symbol, which looks like an inverted foetus, and use it to illustrate your fantastic control over the English language every time you go online (insert Sarcmark).22

Others, echoing the hoary criticism that irony marks were unnecessary in the first place, argued that it is the writer’s duty to convey sarcasm well or to avoid it entirely. Tom Meltzer of The Guardian covered the creation of the mark in a story written entirely in the sarcastic register, and concluded tartly:

The real breakthrough of Sarcasm, Inc is the realisation that, despite having used sarcasm and irony in the written word for hundreds of years, humans are simply too stupid to consistently recognise when someone has said the opposite of what they mean. The SarcMark solves that problem, and you can download it as a font for the reasonable price of $1.99 (£1.20). Our prayers are answered.23

Still others seized on its attempt to put a price on a punctuation mark, accusing the Saks of a cynical attempt to monetize free speech. Josh Greenman himself weighed in with a lengthy column published by his new paper, the New York Daily News, taking umbrage at the idea:

[T]rademarking a punctuation mark – trying to own the very stuff of thought – is like patenting a DNA strand. It’s messing with the very stuff of life. Get out of my head, evil corporate overlords.24

Nor was the backlash confined to opinion pieces. A scant month after the first SarcMark press releases had been sent out, another front was opened in the form of the ‘Open Sarcasm’ movement, a mock-revolutionary website calling for the SarcMark to be blacklisted in favour of the tried and tested inverted exclamation mark, or temherte slaq. Affecting a militant stance against the ‘greedy capitalists of Sarcasm, Inc.’, the site declared:

A spectre is haunting the internet—the spectre of Open Sarcasm.

Of late, certain capitalist forces have brought forth onto the internet the idea that sarcasmists everywhere must license and download their proprietary new “punctuation”—called the “SarcMark”®—in order to clarify sarcasm in their writing.

A growing chorus of voices has joined together to decry this idea. It is high time that Open Sarcasmists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the Spectre of Open Sarcasm with a manifesto of the punctuation itself. […]

SARCASMISTS OF THE WORLD, UNITE!25

The rapid appearance of an entire website dedicated to the ‘forcible overthrow’ of the SarcMark was the very embodiment of internet activism: a deadly serious message inveighing against the rise of capitalism over collectivism; proprietary over open standards; intellectual property over free speech; and all delivered with a healthy undercurrent of knowing humour.

All this, though, is perhaps to miss the point. Despite the righteous fury levelled at it from all quarters, the SarcMark had already succeeded in doing what no punctuation mark since the interrobang had done: it broke into the rarefied atmosphere of the mainstream media. Which other new mark of punctuation could claim to have received coverage in the New York Daily News, The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and at ABC News?20 The most reviled sarcasm mark of all may yet prove to have been the turning point in the irony mark’s long history of distinguished failure.

- 1.

-

“Sarcasm”. Oxford University Press, October 2011.

- 2.

-

Liloia, Tara. “The Sarcasm Mark”. Tara Liloia, August 8, 2001.

- 3.

-

Danet, B. “ASCII Art and Its Antecedents”. In Cyberpl@y: Communicating Online, 194+. Berg, 2001.

- 4.

-

Press, The Associated. “Digital ’smiley face’ Turns 25”. MSNBC, September 2007.

- 5.

-

“Tilde”. In Urban Dictionary. Urban Dictionary LLC, October 2011.

- 6.

- 7.

-

Greenman, Josh. “A Giant Step Forward for Punctuation¡”. Slate.

- 8.

-

Speckter, Martin K. “Interrobang”. Edited by Martin K Speckter. Type Talks, no. Nov-Dec (1968): 17+.

- 9.

-

Greenman, Josh. “Telephone Interview”. Keith Houston, December 2009.

- 10.

-

“Code Charts - Scripts”. The Unicode Consortium, September 22, 2011.

- 11.

-

Tsigie, A, B Beyene, D Aberra, and D Yacob. “A Roadmap to the Extension of the Ethiopic Writing System Standard Under Unicode and ISO-10646”, 2008.

- 12.

-

Cunningham, Choz. “Irony Mark???”. Punchcut, October 14, 2006.

- 13.

-

Cunningham, Choz. “The Snark » History”.

- 14.

-

Cunningham, Choz. “The Snark » Design”.

- 15.

-

Jacobs, Bas. “Irony Mark, and the Need for New Punctuation Marks”. Underware, 2007.

- 16.

-

Jacobs, Bas. “Personal Correspondence”. Keith Houston, September 2011.

- 17.

- 18.

-

Gordon, Andrea. “Hitting the Mark With Sarcasm”. Toronto: Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, January 2010.

- 19.

-

Sak, Douglas J, and Paul Sak. “SarcMark Info”. Sarcasm Inc, 2010.

- 20.

-

Heussner, Ki Mae. “Sarcasm Punctuation? Like We Really Need That”. ABC News.

- 21.

-

Moore, Matthew. “Sarcasm Mark Aims to Put an End to Email Confusion”. London: Telegraph Media Group, January 2010.

- 22.

-

Broughall, Nick. “SarcMark: For When You’re Not Smart Enough To Express Sarcasm Online”. Allure Media, January 13, 2010.

- 23.

-

Meltzer, Tom. “The Rise of the SarcMark – Oh, How Brilliant”. London: Guardian News and Media, January 2010.

- 24.

-

Greenman, Josh. “Sarcastic People of the World, Unite: In the Name of Insincerity, Take down the SarcMark”. New York Daily News.

- 25.

-

Open Sarcasm. “Open Sarcasm Manifesto”.

- *

- ASCII, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, has been previously discussed on Shady Characters and is synonymous with the

fixed-width typefacesoften used to compose emoticons and other ‘ASCII art’.3 ↢ - †

- See The @-symbol, part 1 for a brief history of the ARPANET. ↢

- ‡

- The ongoing quest to denote online sarcasm was acknowledged by none other than the W3C, the web standards organisation, in an exchange of tweets with designer Gianni Chiapetta:6

- Gianni Chiapetta (@gf3)

- Proposed HTML 5 tag: <sarcasm>. To help clear up some online misunderstandings. (@w3c am I right?)

- W3C Team (@w3c)

- @gf3, <sarcasm>you are right<sarcasm/>

- §

- Martin Speckter would have been gratified to know that the interrobang has its own representation, or ‘code point’, within the Unicode standard. ↢

- ||

- Unicode characters are often written as a hexadecimal number, where each digit is represented by a number in the range 0-9 or a letter in the range A-F. ‘U+00A1’ indicates the Unicode character numbered A1, or 161 in decimal terms. ↢

- ¶

- At the time of writing, thesnark.org has been replaced by a holding page stating that “The website you were trying to reach is temporarily unavailable.” ↢

Comment posted by Bryan Price on

And here I thought this was the irony mark – ⸮

& # 11822 ; in web speak.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Bryan,

The reversed question mark is certainly an irony mark, though like all the rest of them it has never quite caught on. It was also used to punctuate rhetorical questions, and I’ve written about it in this capacity here and here.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Matthew Kay on

One sarcasm indicator that I don’t think you’ve mentioned is the use of “/s” to punctuate sarcastic posts on forums like Slashdot and Reddit. It started as a joke, I think: posters would wrap sarcastic statements in the pseudo-HTML <sarcasm></sarcasm>, and eventually it lost the opening tag and most of the closing tag. I don’t know when or where it originated (likely on Slashdot or some earlier forum, years ago), but it is still used today.

Comment posted by Matthew Kay on

Oh, your comment system ate my pseudo-HTML. It should read “… the pseudo-HTML open-angle-bracket sarcasm close-angle-bracket open-angle-bracket /sarcasm close-angle-bracket, …”

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Matthew,

I’ve fixed your comment. WordPress attempts to interpret thing that look like HTML tags as HTML tags, and angle brackets per se get lost as a result.

I did mention the <sarcasm/> pseudo-tag in a footnote, but I wanted in general to steer clear of non-punctuation-style marks.

Thanks for the comment, and I hope you enjoyed the article!

Comment posted by Avery on

On MetaFilter, the word HAMBURGER at the end of a sentence denotes sarcasm. There’s some in joke about it which I forget.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Avery,

Thanks for the comment!

The “HAMBURGER” practice arose when someone proposed that “{/}” should be appended to sarcastic statements on Metafilter. Someone else responded that “{/}” looked like a hamburger. The legend was born.

Comment posted by Jacob on

Thanks for an “interesting”, “well-written”, and “nice-looking” series. But you didn’t mention (except in a quotation) the most common sarcasm marks.

I agree with the Guardian writer, though; where’s the fun in being ironic if you have to tell people you’re doing it? It’s like laughing at your own jokes.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jacob,

I decided to concentrate largely on punctuation-like characters — the inverted exclamation mark, the kerned dot-plus-tilde snark, the SarcMark and so on — at the expense of alphabetic or compound sarcasm indicators like <sarcasm/>, ‘/s’ and

:-). You’re right, though, and I could have mentioned “scare quotes” too. There are more ways to signal irony than I had time to cover!Thanks for the comment, though, and I have to agree with you. A nicely crafted bit of verbal irony is far more satisfying than appending a mark which shouts “look! I know irony.”

Comment posted by Jon Ericson on

I love the idea that someone thought that you can’t use ;-) (my “don’t take the previous sentence 100% seriously” mark of choice) in a business email, but sarcasm is A-OK!~ Hint: it isn’t professional to say something other than what you mean in formal correspondence¡ Plus, after while, the mark’s meaning will become diluted, as people, who don’t know how to use them, just add marks randomly [insert SarcMark here]. You know, like commas. ;-)

Comment posted by Joe Pallas on

Have we really reached the point where so few people even recognize that there is a difference between irony and sarcasm? The first two parts of this piece were blessedly free of that confusion, but this final part failed to offer a single sarcastic aside about people mislabeling irony as sarcasm. The notion that un-ironic sarcasm would need to be labeled to be recognized is laughable, and the idea that ironic sarcasm (which would be “sharp, bitter, or cutting”) should be acknowledged with a wink is absurd. Anything that befits a wink is far too gentle to be called “sarcasm.”

Oh, dear. I sound like a terrible curmudgeon, don’t I? Despite that, I appreciated the piece immensely. Thank you.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Joe,

Strictly speaking, sarcasm is a form of irony — I’m not sure of the linguistic term, but as a software engineer I’d say that sarcasm “specialises” irony — and there have been so many recent attempts to create marks to convey one or the other that I decided to follow both threads.

You’re right in saying that irony is often now mislabelled as sarcasm, though I’d be tempted to say that this is just common or garden linguistic evolution. It might not be entirely correct to use the word ‘sarcasm’ when ‘irony’ would be more accurate, but I’d hope that most readers/listeners would understand the sentiment.

Anyway, I’m glad you enjoyed the article, and thanks for the thought-provoking comment!

Comment posted by Steve Howlett on

In the subtitles to TV programmes, an ironic or sarcastic comment is followed by a bracketed exclamation mark. If the comment is a question, the question mark is in brackets. The intention is usually clear to myself and my hearing-impaired partner.

Comment posted by Anthony Bailey on

I infer from reading your excellent post that almost every well-intentioned attempt to improve communication through the introduction of punctuation to signal irony has failed to achieve critical mass – and has therefore presumably confused most readers who encountered it.

Of course some future attempt – especially one targeting sarcasm – will succeed!

(Attempts at implicit self-reference, on other hand…)

Comment posted by Owen on

Keith,

the source document #11, as I read it, contains a different Unicode reference (U+00A1) from that quoted in your article (U+00A16). The latter is actually the Gurmukhi Letter Kha, while the former is the referred to inverted exclamation mark. I also think the related footnote [‖] could be altered to better reflect how hexadecimal works by removing “… where each digit is multiplied by 16, rather than 10 as for decimal numbers, and …” (or possibly dispense with the footnote altogether). This minor point aside, another good read as always. Thank you.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Owen,

Thanks for catching that! I’ll update the text accordingly.

I understand your point about the footnote; I wanted to explain the otherwise cryptic Unicode code point syntax, but perhaps it could be reworded.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Leonardo Boiko on

The tilde wouldn’t work for an East Asian audience; it’s currently in informal but widespread use (often as its double-width cousin, the wave dash or nyoro ~) to indicate an effect parallel to the extended, oscillating vowels of musical or “cute” speak. For example, in「ですよね~」 “desuyone~” the wave represents an overdrawn emphasis on the “ne”.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Leonardo – thanks for the comment! Is the tilde (or wave dash) used in this way to modify written or spoken language, or both?

Comment posted by Tab Atkins on

Both, from my own experiences. It’s definitely used in informal transcriptions of “cute speech”, but it’s also used in purely-written language, such as chat rooms. My (non-Japanese, but anime-watching) wife uses it in a similar sense when txting or IMing in English to indicate a “cute” or “mischievous” mood.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Tab — thanks for that. That’s a great example of the “alternative, contradictory meanings” I mention above that militate against the tilde ever being seen purely as a sarcasm mark.

Comment posted by Rudi Seitz on

Thank you for this informative series. (And I admire the visual design of your site!) One point I’d like to know more about is the Temherte Slaq. I gather it has wider adoption in its own cultural context than any of the proposals for a sarcasm mark have gained in the English-speaking world? So, is there something specific about that context that made the Temherte Slaq take hold there?

On another note, I’ve just today undertaken my own series of experiments with the sarcasm mark, unfortunately ending in frustration (warning: the post contains sarcasm): http://rudiseitz.com/2013/01/02/irony-mark/

Also, I have a proposal for distinguishing ironic questions from ironic statements by giving them separate marks: http://rudiseitz.com/2013/01/02/punctuating-ironic-questions/

Have I reinvented the wheel here?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Rudi,

I think you hit the nail on the head when write in your post that “You might wonder whether I’m making fun of the idea of the irony mark. I’m NOT making fun of the irony mark.” The problem with the irony mark, of course, is that it is not always clear whether the writer is using it sincerely or ironically.

Personally, if I had to come down on one side of the argument or the other, I’d favour using the reversed question mark in its original guise as a percontation mark to indicate a rhetorical question rather than an ironic statement.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Catherine Barber on

What about the ‘(!)’ sign – isn’t this supposed to be an ‘irony’ mark?

I’ve seen this used as such, online – and have taken the liberty of using it myself (I hope with discretion). But when I googled this, nothing could be found about it.

I like the look of it and hope this would become a standard piece of punctuation.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Catherine — you’re quite right. ‘(!)’ is used for sarcasm, although formally speaking it seems to be confined to televisual subtitles — see here, for instance. This document, which comes from the UK broadcasting watchdog Ofcom, says that ‘(!)’ should be used for sarcasm and ‘(?)’ for irony. These are notable in that they’re officially sanctioned, to some degree, which is not something that can be said of many other such marks. Perhaps this is the way forward for written irony and sarcasm marks?

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Jonny on

I love this article. NOT.

Just kidding. I really enjoyed it. I promise, no sarcasm there.

I love the almost recursive irony in trying to find a method of being explicit about it. One of the most fun parts of sarcasm is that you cannot guarantee that the sarcastic intent will be detected.

I also love that the most earnest efforts accidentally produced a nazi symbol. Very funny.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jonny — I’m glad you enjoyed the article. And you’re bang on about the shortcomings of irony marks. Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Choz Cunningham on

How am I just now finding this article?!

I appreciate the thoughtful commentary on the advantages and disadvantages of the approaches to an “irony mark” in this article. Particularly, when you understand why I used the technical approach I did.

To further explain the purpose of the snark, it is neither precisely an irony mark, nor a sarcasm mark. Nor is it quite “both”, but that is closer. It is a mark to simulate vocal intonation — vocal intonation that is often used when being sarcastic, and sometimes when in a certain mode of irony. Should irony always be proclaimed in punctuation? No way! The purpose of the snark is to only be used where there would be a pronouced change in one’s speaking, were one to say the words out loud.

Btw, I have recaptured the domain and hope to have The Snark up and running again shortly. (Also, I continue to include snarks in all my typefaces.)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Choz,

Thanks for stopping by! It’s gratifying to have one of the people I’ve written about get involved in the conversation about their respective marks. I appreciate the clarification in how the snark is to be used (as vocal “stage direction”, so to speak), and that certainly sets it apart from the other marks. Can I ask: when you design a snark for your fonts, do you use some sort of combining diacritic mechanism to display it, or is it a standalone character?

Also, it’s good to see that thesnark.org is online again. I’m keen to see how things progress!

Comment posted by Choz Cunningham on

Glad to be here, and moreso to see the snark get attention. I see a similarity between the snark and the the vocal direction of exclamation and inverted question marks. An exclamation mark alters the tone of a sentence, and can be use several ways – for alarm, happy surprise, emphasizing a twist, or to press a short phrase into use as an interjection. The inverted question mark exists, if I understand correctly, for use in languages where the syntax of a question is identical to a statement, emulating a vital rising tone before the reader gets to the terminal question mark.

My ambitions with thesnark.org are mild. I intend to host but a few pages explaining the purpose of the mark and the various ways for a font user to apply it. For type and font designers I also plan on adding brief info on and my methos of glyph construction and style intentions.

That construction method, is two- (.ttf) or three- (.otf) fold. I do not use a combining character approach, because I imagine the snark being designed as a custom ligature. There are a few choices that can improve on merely typing “.~” depending on the type face, particularly connected or condensed faces. and it can be made “prettier” designed from scratch. Also, I just love ligatures. I then put the character in the Unicode Private Use Area at U+E2D2. Finally, when I am making an OpenType font, I add it to the ligature replacements.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Choz — that is all enlightening stuff. I see your point about the exclamation mark being as much about vocalisation as it is about semantic meaning, though surely the semantic meaning is also important — if it wasn’t, would anyone ever use ‘!’ in an email or a newspaper article that they never intended to be read aloud? I’d say that if the snark is mostly about a snarky tone of voice, it should certainly carry a sarcastic or ironic meaning along with it for purely written use.

Comment posted by Choz Cunningham on

I’m not certain I am qualified to speak on the sematic qualities of punctutation, be it regarding a snark or a exclamahine point. I do beleive the common consensus is that we think in words, altough I think that might be an oversimplification. Building on that, I, personally, insert some rudimentary voice to what I read, perhaps at the final stage of interpretation. Just as studies show we scan ahead as we read words, to give them more context, I think suspect we build a narrative style on the fly, as if we were reading aloud (though much faster, and more Spartan fashion). No idea how to test to if that is universal, though. All that is to say, that I am not sure that the vocal and sematic traits are separate. Is reading a “!” and different than hearing one?

If that is not the case today, I would think, if the snark became culturally integrated, it would grow to function semanticly similarly to other “narrative” punctuation? I say that to contrast with punctuation that are more like abbreviations like “&”, “@”, and “$”.

Comment posted by Choz Cunningham on

If I can add my own speculation on one more point, I am sure that the “the click-to-publish ease of the web” has had an effect, just like type design has blossomed, for better or worse, the possibility of a solution has become easier to construct as well as spread to others. But what is important, I feel is what is the motivation for designers to explore this.

Prior to the rush of packaged “offical” irony marks, the masses demand for something to do the job relatively surged. That non-designers impliment winkies, brace coversations in a pair of tildes, tags, or just tack on a “lol” after a sentence displays the desire people have. This change is still tied to the growth of the Internet, but for another reason.

Real-life people never fused writing and real-time casual conversation until the end of the 1980’s and the rise of IRC. This has been followed by standalone instant messengers, sms texting, and integrated chat in social networking technology and tech support. And this trend keeps growing. This is an entirely different way of using written language than was common before, if at all. Concientious phrasing, contemplation of one’s own words and revising, all before you pass your words to the reader, doesn’t apply in this arena.

Looking at closed captioning is interesting in this case, I feel. CC has it’s own mark for irony/sarcasm, and it’s not a coincidence. Transcribing spoken words on live TV or on Google Hangouts is very similar, where words come just-in-time and don’t get a chance at a rewrite. In scripted TV, I feel the same idea still applies, as they write to create the illusion of spontaneous talk.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Choz — you’re right; the snark will take on both a semantic interpretation if it makes it into mainstream use, whether or not it is intended to have one!

I may be misunderstanding what you intend for the snark to do, but I do wonder if it would be better to position it, unambiguously, as a sarcasm mark, without any mention of its more subtle shadings as a signifier of a particular kind of spoken sarcasm. It can still be optional, in the same way that the ‘!’ is optional, but I think you might have fewer battles to fight over the nuances of its usage if you were to leave the spoken implications of its use to those who read it aloud.