Well, ✨that was fun✨❗ For now, though, it’s time to work our way through some of the punctuation-related links and news articles that have cropped up during our stay in emojiland. Stick around; there’s some great stuff to come.

First, via the always fascinating Language Hat, comes word of a paper entitled “Pull out all the stops: Textual analysis via punctuation sequences”.1 In it, Darmon, Bazzi et al ask the question: is it possible to identify individual writers using only their punctuation? That is, if you remove the words from a piece of writing, can you mathematically fingerprint the writer by the marks that remain? The answer is a firm “sort of”. I’ll leave you to read the full paper to find out more.

Next up, Russell Harper, editor of the Chicago Manual of Style’s “Shop Talk” blog, delves into breaks in fiction. You know the ones I mean — more significant than a new paragraph but less significant than a new chapter, and typically separated by blank lines, asterisms (* * *), bullets (• • •), or other typographical flourishes. Russell investigates the means by which various authors (or the typographers who designed their books, or perhaps both in concert) chose to set off breaks in their novels with varying degrees of success.

On the subject of significant breaks, I am extremely late in bringing to your attention an intriguing tweet published by Katie Henry back in 2018, but it is too good not to share:

If you ever feel self-conscious about your writing, please know that in 1802, a man named Timothy Dexter published a 9,000-word book with seemingly arbitrary capitalization and literally ZERO punctuation.2

And it gets better. The book in question is called A pickle for the knowing ones, or, Plain truths in a homespun dress,3 and it was self-published by the aforementioned Timothy Dexter as a gift for his friends.4,5 The lucky recipients must have been bamboozled by its contents: Dexter used unpredictable capitalisation and a spelling system of his own invention. What he did not use was punctuation: neither a comma nor a full stop was there to interrupt his stream of thought.5 Here, for reference, is the opening passage, cut off at what seems to the end of a sentence:

Ime the first Lord in the younited States of A mericary Now of Newburyport it is the voise of the peopel and I cant Help it and so Let it goue Now as I must be Lord there will foller many more Lords pretty soune for it dont hurt A Cat Nor the mouse Nor the son Nor the water Nor the Eare then goue on all is Easey Now bons broaken all is well all in Love Now I be gin to Lay the corner ston and the kee ston with grat Remembrence of my father Jorge Washington the grate herow 17 sentreys past before we found so good a father to his shildren and Now gone to Rest6

Well, alright then. As Randy Nelson explains in The Almanac of American Letters, “Literary historians have never been able to decide whether this little book is hoax, lunacy or avant-garde.”5 Certainly, Dexter might have harboured any or all of those motivations. Born a commoner, Dexter styled himself a lord and made a fortune through a series of improbable business deals — among others, he exported coal to the mining mecca of Newcastle during a miners’ strike, and repurposed bed-warming pans as cooking pots for molasses and sold them in the Caribbean. With his money he established a retinue comprising a fortune-teller, a simpleton and a pornographer, and housed them in a mansion surrounded by wooden statues of notable figures. Himself included, of course.4

For the second edition of Pickle (eight would be published), Dexter acknowledged that some readers might have had trouble with his lack of punctuation. Accordingly, he wrote,

the Nowing ones complane of my book the fust edition had no stops I put in A Nuf here and thay may peper and solt it as they plese

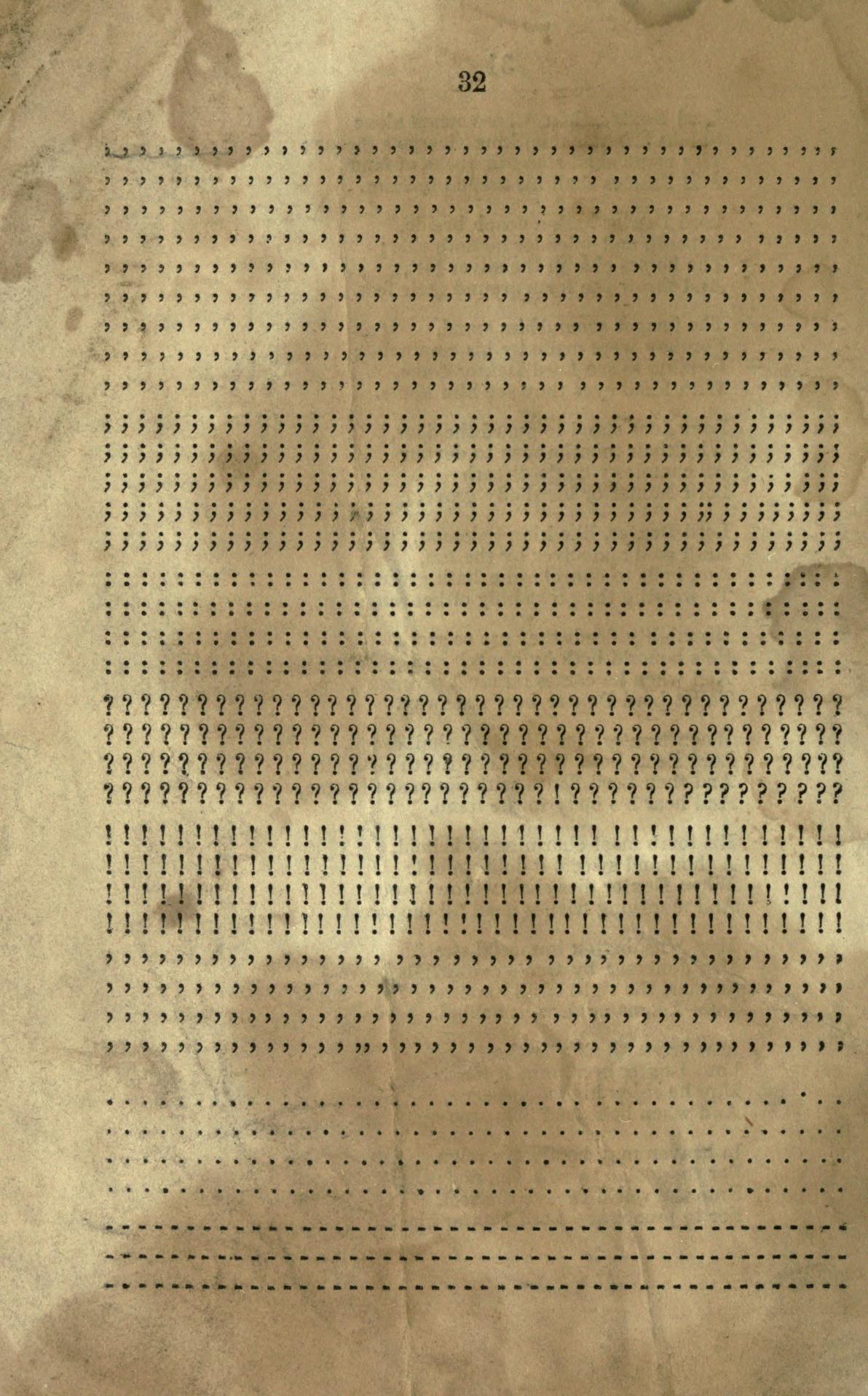

Here is that very same peper and solt as it appeared in the fourth edition:

Lastly, reader John Chulick brought to my attention Adam O’Fallon Price’s essay on the em dash, or ‘—’, published in 2018 at The Millions.7* Price explores em dashes in the works of Vladimir Nabokov, Emily Dickinson and others, and I’ll leave it to him to explain why the mark is worth our attention:

For me, there is no punctuation mark as versatile and appealing as the em dash. I love the em dash in a way that is difficult to explain, which is, probably, the motivation of this essay. And my love for it is emphasized by the fact that many writers never, or rarely, use it — even disdain it. It is not, so to speak, an essential punctuation mark, the same way commas or periods are essential. You can get along without it and most people do. I don’t remember being taught to use it in elementary, middle, or high school English classes; I’m not even sure I was aware of it then, and I have no clear recollection of when or why I began to rely on it, yet it has become an indispensable component of my writing.7

On a related note, Stan Carey, another must-follow at Sentence First and Strong Language, also wrote about dashes in 2018. Stan focused on the em dash’s abbreviated sibling, the en dash, and specifically its use to hyphenate compound terms. I remember being tickled at the concept upon learning of it in the Chicago Manual (it is as subtle as it is useful), and Stan more than does it justice at Sentence First. Well worth a read!

- 1.

-

Darmon, Alexandra N M, Marya Bazzi, Sam D Howison, and Mason A Porter. “Pull Out All the Stops: Textual Analysis via Punctuation Sequences”. SocArXiv, January 2019.

- 2.

-

- 3.

-

Dexter, Timothy. “A pickle for the knowing ones, or, Plain truths in a homespun dress”. Printed for the author, 1802.

- 4.

-

“Coals To Newcastle”. In The Reader’s Digest book of strange stories, amazing facts, 501. London: The Association, 1975.

- 5.

-

Nelson, Randy F. “A Pickle for the Knowing Ones”. In The almanac of American letters, 206-207. Los Altos, Calif.: W. Kaufmann, 1981.

- 6.

-

www.LordTimothyDexter.com. “A Pickle For The Knowing Ones - Split Pickle - Folio 1 4”. Accessed March 14, 2020.

- 7.

-

Price, Adam O’Fallon. “Regarding the Em Dash - The Millions”. The Millions.

- 8.

-

Maynard, Nora. “You Call That a Punctuation Mark?! The Interrobang Celebrates Its 50th Birthday”. The Millions, March 13, 2012.

Comment posted by emiliɯe on

markup-breaking typo in penult paragraph:

bibicite⇝bibciteComment posted by Keith Houston on

Aha! Thanks for catching that. Fixed now.

Comment posted by Dick Margulis on

The windmill I continue to tilt at is the contemporary confusion of a punctuation mark we indeed were taught in elementary school, namely the dash, and the typographic representation of that mark, typically an em rule (em dash) in the US and a spaced en rule in the UK. A dash is a dash whether it is represented by a pen or pencil stroke, by two typewriter hyphens (or one, spaced) or by a typographic device. “Em dash” is not a punctuation mark.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

A good point. Double/single quotation marks and em/en dashes aside, I wonder if any other typographical marks trade places from language to language.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Glenn Fleishman on

Dick, you may need to send a letter to the past, because the term “em dash” has been in use by typesetters and printers since the mid-1800s. I knew this from research of the last couple of years, but just did a quick refresher to find contemporary sources, and they abound. As a recovering typesetter myself, I share your concern about the devaluation of printing-related words (the Atlantic wrote an entire story about the “en space” when the writer meant a common word space, often four- or five-to-the-em). But I will not cede the point! Unless you have some great textual evidence, which I am dying to see.

Comment posted by Dick Margulis on

Glenn, I’m in complete agreement. I fear, though, that you have misunderstood my point, which is that a typographic device—the em dash—is categorically different from the symbol—the dash—that it represents. When writers and editors use “em dash” instead of “dash,” they are making a category error, conflating the symbol with one means of instantiating it. And when they further try to draw a semantic distinction between two entirely equivalent means (em dash and spaced en dash) that merely conform to two different house styles, they confirm, for me, how thoroughly muddled their thinking is.

Comment posted by Glenn Fleishman on

I see! This is a little abstruse, but I will agree it’s a worthy meaning to distinguish. They mean “a device that indicates a certain kind of pause” but they are saying “a specific typographic element, which may vary by country or even between typists and media, due to practice or glyph availability.”

Although, you are arguing between precision and common usage. In a textbook on writing or design, I would want this distinction. As a shortcut in speech, maybe not. Though I have, in fact, had confusion between US and UK people in talking about em and en dashes, which would argue towards your view being correct!

Of course, I have to ask if you’re aware of the three-em dash! (Unicode ⸻)

Comment posted by Dick Margulis on

Glenn, I’m an old hand. I’m aware of a great many things. Let’s not bore the spectators any more than we have already.