On Mastodon (or rather, on fediscience.org, a server powered by Mastodon), Marc Schulder asks:

What do you call the list of teaser phrases at chapter beginnings in novels like “Three Men in a Boat” or “Going Postal”?

So far I’ve found “epigraph”, which is not specific enough, and “taster”, which possibly is not what book people would call it.

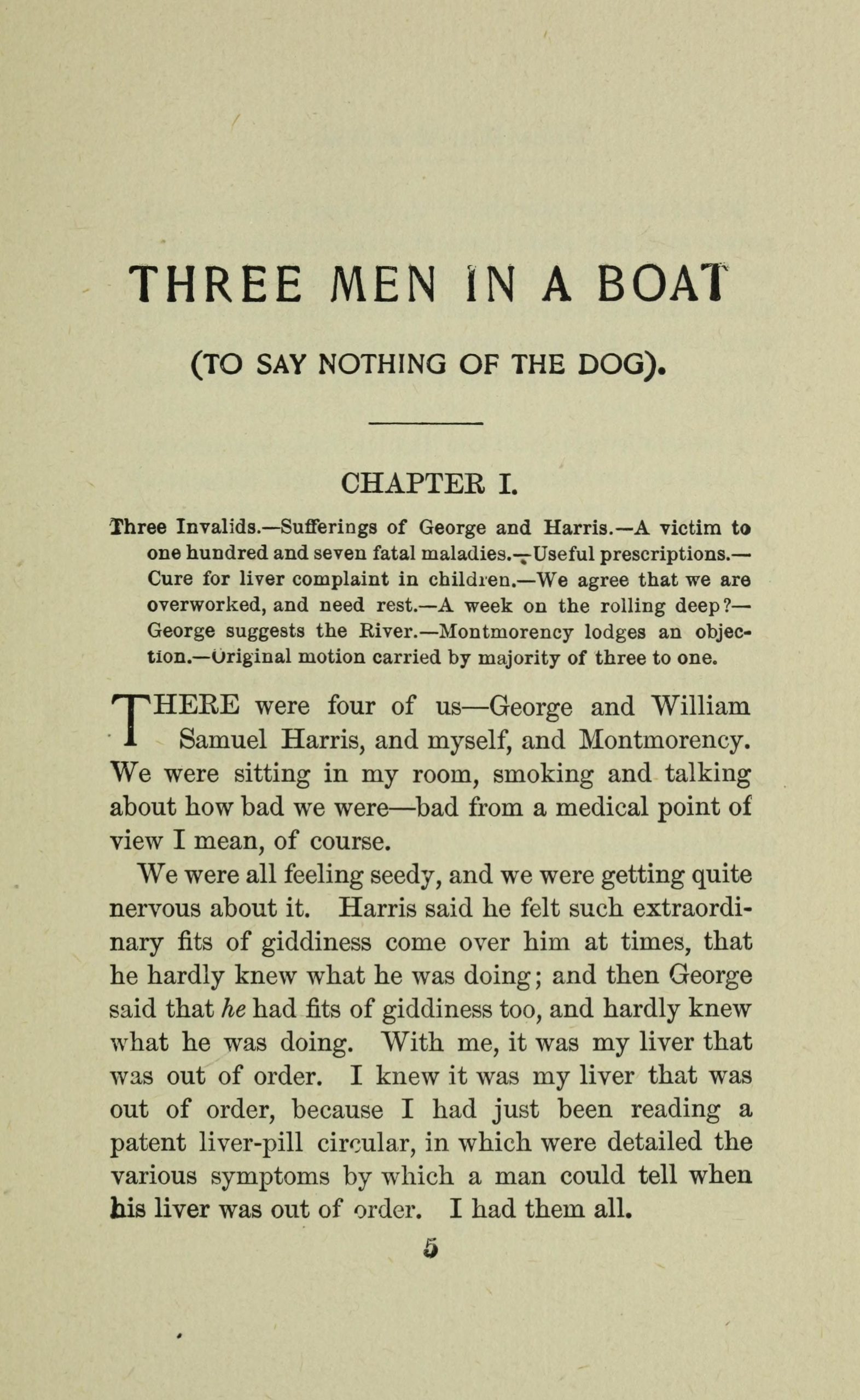

Courtest of the Internet Archive, here’s the first page of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, taken from an original 1889 edition:

For the avoidance of doubt, Marc is asking about this part:

Three invalids.—Sufferings of George and Harris.—A victim to one hundred and seven fatal maladies.—Useful prescriptions.—Cure for liver complaint in children.—We agree that we are overworked, and need rest.—A week on the rolling deep?—George suggests the River.—Montmorency lodges an objection.—Original motion carried by majority of three to one.

It’s a sort of table of contents, really, but rather than pointing to concrete locations in the text (such as catchwords or headers), it summarises the chapter’s contents instead.

I’ve seen this kind of thing before, as I’m sure many of us have, but it isn’t something I’d ever seen given a name. Some web searching did not turn up anything very convincing, and so I forwarded Marc’s query to my editor at W. W. Norton, Mr Brendan Curry. Brendan put Norton’s finest on the job and here, lightly edited, are their responses.

First up is Rebecca Homiski, Managing Editor. (Proposed terms are in small caps.)

My first hit was on a message board with some interesting asides; here, this feature seems to be referred to as a “nutshell.” The second search result was a New Yorker article about the history of the chapter, which definitely refers to this practice but dances around a term for it.

Rebecca also mentions this intriguing link:

And then came a brief discussion of tropes which referred back to “arguments” presented before sections of Renaissance-era poems.

Here, Rebecca links to the TV Tropes website, which is a wiki that catalogues many of the conventions, themes, and clichés that appear in TV programmes, films, books, and other forms of media. Collectively, tropes. Now, TV Tropes has a trope of its own in which the word “trope” is often used as a placeholder or boilerplate term. And so, the page that to which Rebecca links — the page that describes the practice of summarising the chapter of a book — is titled “In Which a Trope Is Described”. All of which is clever, but not especially pithy as a term of reference.

Ignoring that last term, then, we find that chapter summaries may be referred to as “nutshells” or, perhaps, “arguments”.

Don Rifkin, Associate Managing Editor, weighs in with a few more examples:

On this page, they’re referred to as “chapter contents”: “Chapter contents can be useful in histories or any book with long chapters that cover a variety of people or topics. This is like a mini Table of Contents specific to each chapter.”

Words into Type has a section on them and refers to them as “synopses” (p. 252, 3rd edition, 1974).

I see no consensus on a term for them, so I would think it’s fair game what to call them.

Okay then. Let’s add “chapter contents” and “synopses” to our list.

Robert Byrne, Trade Project Editor, adds a perceptive comment:

If they had a standard name, I suspect whatever it was may have been a specialized term mostly used in the publishing biz, which is maybe why it’s hard to find any literary connoisseurs and scholars mentioning them. Which is of course why we’re now desperate to know.

Well, quite.

Marian Johnson, editor of the Norton Anthologies, also contributed some of the same definitions we’ve seen above. I’m grateful to her, and to all at Norton who got their teeth into this question, and to Marc Schulder for asking the question in the first place. The answer to that question, then, as close as we can say, is that chapter summaries can be called “nutshells”, “arguments”, “chapter contents”, or “synopses”.

Comment posted by Roger W Turner on

Glosses, surely.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Roger — that’s a neat suggestion. But I’d always thought of glosses being more of an explanation than a summary. These “nutshells” are deliberately shortening what’s to come, not explaining it. Does that make sense?

Comment posted by Dick Margulis on

I have no evidence that this term has ever been applied to the device, but if I had to come up with a name, I’d call these abstracts.

Comment posted by Long Branch Mike on

I quite like the suggested term abstract, which is of course from the scientific realm to provide a summary of the contents of a paper for quick scanning, not literary. Although as a science grad, I am partial to this word. Of course, the other stated words and suggestions also work quite well: synopsis, nutshell, summary… depending on the writer’s perspective or background.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Dick, Mike — “abstract” is a nice term. It feels right, although dare I say it’s lacking in drama.

Comment posted by NotRexButCaesar on

How are the word break areas determined? I notice there is some kind of zero-width break character in many on the words, some of them etymological & a few not etymological. Are these simply syllable breaks for large words, or are the non-etymological breaks mistakes?

Comment posted by NotRexButCaesar on

(I know these are not syllable breaks because words like chap•ter have no break.)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi NotRexButCaesar — hyphenation is carried out using the Hyper library, which in turn uses a word break algorithm developed by Franklin Huang in the early 1980s.

I’m working on a new version of the site that will use native CSS hyphenation, which should remove the need for these discretionary hyphens.

Comment posted by Brian on

In my (amateur) experience, in typography this section is called a “precis” or a “recapitulation”.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Brian — interesting! Thanks for adding to the list. Do you have any sources for those terms?

Comment posted by Brian on

Frustratingly, all I’ve been able to find is a reference to LaTeX, in which the name of the macro that defines these is

\chapterprecis. (See e.g. http://mirrors.ctan.org/macros/latex/contrib/memoir/memman.pdf section 6.5.3.) I no longer remember where I picked up those terms, and my attempts at doing some targeted web searches have been fruitless.Comment posted by Pipistrello on

Hello Keith. I, too, took a (limited) hunt around the interwebs looking for this term when I did a short review of JKJ’s book and settled on the rather dull “chapter introductions”. I was hoping there’d be some delicious little publishing term to tuck away for future but didn’t find one, nor did the legal and scientific equivalents like headnote and abstract have the right flavour for such whimsy.

Comment posted by Ralph on

I was going to say “argument” before reading the article, but I guess that’s a specialized kind of intro. But as King Harry said, “We are the makers of manners”. Let’s make up our own term, shall we? TV dramas often provide us with a “recap” of what has already occurred, so why not have a “precap” of what’s to come? :p

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ralph — I like this! “Precap”.

Comment posted by Jon Harley on

This was actually the original meaning of an “epitome”: “a summary or abstract of a written work” (Shorter OED). It’s also really close to a “compendium”: “a work presenting in brief the essential points of a subject”. But the common usage of both those words has shifted over time. I like the idea above of the neologism “precap” to define the presenting of key plot points at the start of a chapter of fiction.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jon — “precap” is good, isn’t it? I do like “epitome”, too, since it isn’t commonly used for anything similar. “Abstract”, by contrast, sounds correct but it’s too closely associated with a very specific type of summary. “Epitome” doesn’t have that problem, at least in the mainstream.

Comment posted by Shalom Bresticker on

I recently edited a non-fiction book in which at the beginning of each chapter, the chapter title was followed by a list of the subsection titles, each followed by a period. That is, formatting similar to what is shown in your example, but without the dashes. I don’t have a name for that, either. But it is not just for fiction.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Shalom — interesting! I don’t think I’ve seen this in non-fiction before. I’ll have to keep my eyes open.

Comment posted by CL on

I remember them being called “precis” by a prof of mine, and they are referred to that way in the LaTeX typesetting world, though I don’t know why.

I prefer “nutshell” simply because it can be referred to as “the nut” in various ways.

Comment posted by Kate Rogers on

In law, these introductory notes are called “head notes” and I have seen the term used in relation to such introductory chapter notes in non-fiction.

Comment posted by Popup on

I have (internally) called them “inwich” (probably pronounced with a silent ‘w’) – as they’re normally of the form “Chapter X – in which our hero is put in mortal danger – and discovers an important clue.”

But I also like “precap”.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Popup — now that’s a novel suggestion! Your use of “inwich” seems to describe something very similar to TV Tropes’ account of descriptive chapter titles.

Comment posted by Trevor Jordan on

Might they be called “previews”?

I realise, perhaps somewhat guiltily, that I have never read these, preferring to jump straight into the main text without knowing what’s to happen before I get to it, and for me a preview steals some of my reading interest.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Trevor — they are a bit spoiler-y, aren’t they? In fact, perhaps “spoiler” wouldn’t be too far off the mark as a descriptive term.

Comment posted by John Komurki on

On a related note, I have always been interested in what purpose these things actually serve. In other words, why do authors create them? It seems they are not actually intended to be functionally useful: I find them impossibly gnomic to read — the art is to whimsically rephrase what actually happens — and (lacking page references) useless as wayfinding devices. Contemporary authors — such as Robert Macfarlane — who create them seem to do so because it gives their chapters a cute, antiquarian air.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John — they don’t seem very practical, do they? I get the feeling that modern writers mostly treat them as a vehicle for out-of-band information — jokes, asides, and so on — that wouldn’t otherwise make it into the chapter itself. I’m not sure they serve a useful wayfinding or summarising purpose any more.

Comment posted by Trajecient on

What was the purpose? (Well, original purpose). They were blurbs before we had blurbs. The first blurb is considered to have been in 1856.

The titling convention described here was standard practice between the 17th and early 19th centuries. In other words, all before the blurb.

Like modern blurbs, they were for marketing. They were to entice readers opening it up in bookstores and thinking about buying it… and like film trailers, they weren’t meant to be an easily accessible summary.

Afterwards, writers have used it for a historic feel.

Comment posted by Joel Mielke on

‘Prechapt’

Comment posted by Trajecient on

I should clarify my previous comment that while the blurb angle made most sense for serialised chapters or opening chapters, it was a broader convention linked to the usage of long book titles, which would see chapters across books being similarly treated.

Comment posted by Brian Inglis on

TeX (by D.E.Knuth@Stanford) documents consistently seem to refer to chapter precis – see bottom of p.92 6.5.3 Chapter precis in: https://texdoc.org/serve/memman/0#page=130, which refers to “Algorithms” by Sedgewick (Ph.D. student of Knuth), which shows these in the ToC, but not in the chapters: https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Algorithms/MTpsAQAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PR6&printsec=frontcover.

Comment posted by Steve Dunham on

I worked in book publishing for about 10 years (approximately 1982 to 1991). I don’t know of a name for these except what I’ve read here today. But I did find a nonfiction book using them: Tramps and Ladies by James Bisset (tramps being tramp steamers and ladies being ocean liners; he was a sea captain). I’m sure I got it from Gutenberg but can’t find it there now.

Comment posted by Ralph on

@stevedunham. Nice example. The book is available through the Internet Archive.

Comment posted by Joel Mielke on

Perhaps an older word “insipit” would serve—as per Stan Knight: “a written phrase in a manuscript, being the opening words of a main section of text.”

Comment posted by Brian Inglis on

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incipit

This is the practice of using the initial words of a document text as a label for a document in lieu of a title e.g. “Inter Gravissimas” is the commonly used label used for the papal bull propagating the Gregorian calendar date reform which starts with those words.

Comment posted by Joel Mielke on

‘Incipit’ (sorry). I blame centuries of mispronunciation of Latin. If I’d thought ‘in-KIH-pit,’ I’d have spelled it correctly.

Comment posted by Joel Mielke on

According to Stan Knight, some medieval manuscripts had an enlarged first phrase or sentence, to start new chapters.

Comment posted by NotRexbutCaesar on

I am reading The City of God by St. Augustine & before each book (chapter) there is a short summary & declaration of purpose just like this. There is also a very short summary or heading before each section. This book was very popular in the past, so I wonder whether it could be the original source of these summary sections in other books.

I believe the reason these pre-chapter summaries are included in The City of God is that it is created from a compilation of letters by St. Augustine. It may be a contributing factor if it is not the source.

Comment posted by Brian Inglis on

These book/chapter summaries and section headings certainly meet the definition of “precis”.

But I doubt many of those fiction writers or publishers read that ancient and lengthy theological treatise.

It seems more likely that this dotted or dashed style of “precis”, providing “teasers” in contents or at chapter heads, may have been introduced for practical reasons, such as ease of review by buyers or in newly popular journals (in the sense of modern magazines).

It may then have become a fashionable, later a standard, feature for certain writers, publishers, genres, or groups.

Perhaps it better emphasized those works of a more imaginative or fictional nature (the original meaning of romance), highlighting either the moral or sensational style.

Later publishing conventions, practices, and realizations may have made these features superfluous, allowing them to fade out of common use.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

“Later publishing conventions, practices, and realizations may have made these features superfluous, allowing them to fade out of common use.” – I find this quite interesting. Given the obvious potential for creative use of these “teasers”, as demonstrated in Three Men in a Boat, what changes to reading/writing/publishing do you think pushed them out?