Readers! Have you ever wanted a better name for “marks of punctuation”? No, me neither. And yet that is exactly what drove James Brown (no, not that one) to produce the page shown here in his rambling, esoteric An English Syntithology: In Three Books, Developing the Constructive Principles of the English Language of 1845.1

Brown, as I found out after following a link from the niche but always interesting Coffee & Donatus (tagline: “Early grammars and related matters of art and design”), was a nineteenth century grammarian from Philadelphia with a passion for cataloguing and codifying the rules of English language. His “Syntithology” was an attempt to retrofit a logical structure onto the evolutionary messiness of English grammar, and he gave it an appropriately lofty-sounding title: the Greek syn- stood for “with” or “together”; tith- was derived from tithemi, “to put”; and -ology came from logos, a “doctrine” or “principle”. He summarised his book as “the principles on which the elements are formed into the compound” — how letters form words, words makes sentences, and sentences paragraphs.*

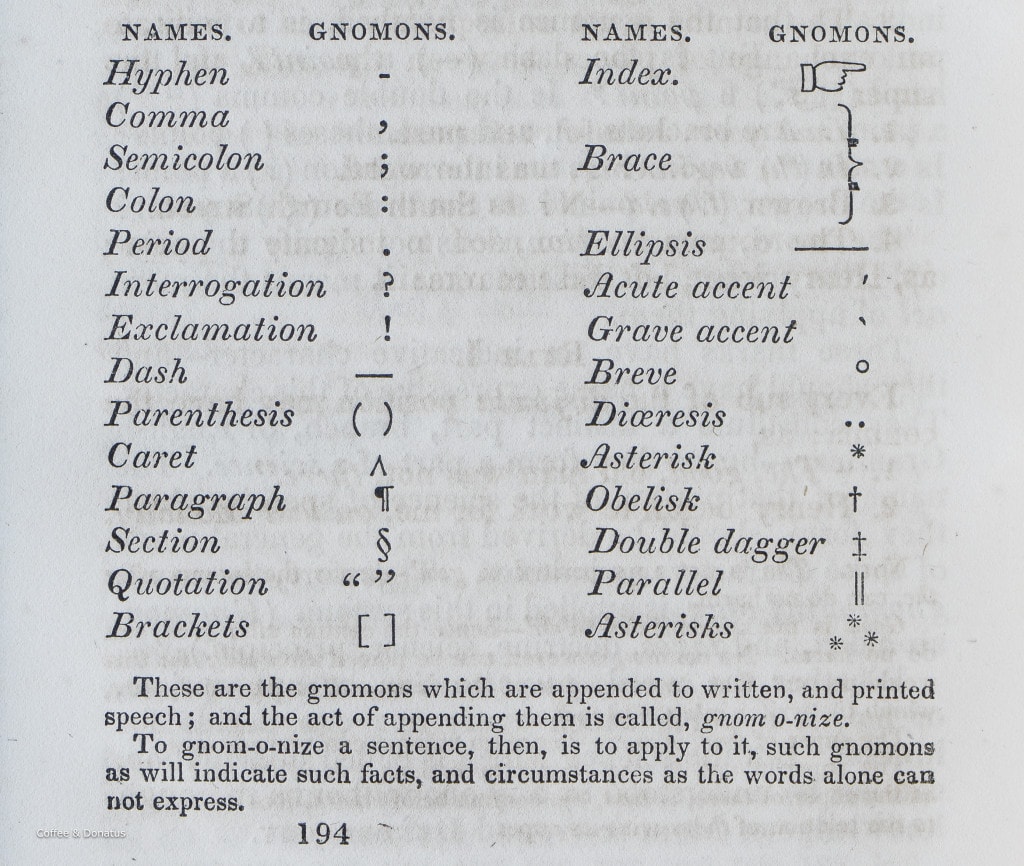

When it came to punctuation, though Brown was happy to call the hyphen, comma and company by their conventional names (I suspect it helped that most such marks had comfortingly classical designations) he could not quite bring himself to leave the subject alone. Punctuation as a whole, he declared, was to be recast as the practice of “gnom-o-nology”.

Gnomonology. For realsies, as the kids might say.

In his chapter on the subject, Brown explained that the Greek word gnomon (“one that knows or examines”) is used to refer the pin or rod of a sundial, the part whose shadow falls upon the dial to tell an observer what time of day it is. For Brown, marks of punctuation were knowing gnomons too — “index marks”, as he described them, that pointed out something of interest in the surrounding words just like a shadow on a dial, and his new terminology was loaded with coincidence.2 The word “punctuation” comes from the Latin punctus, or “point”, for the dots of ink with which early readers marked up their unpunctuated books, though it is not a stretch to imagine these “points” as pointers in a more literal sense. And the manicule, or pointing hand (☞), a mark whose purpose was to highlight interest passages in a text, is also called the index, as Brown showed in his chart.

This drastic re-branding did not take hold. The only other reference I’ve been able to find to Brown’s concept of “gnomonology” is in an 1862 book entitled An analytical, illustrative, and constructive grammar of the English language, written by an English teacher named Brantley York some fifteen years after Brown’s Syntithology, and which lacks Brown’s missionary zeal.3 Today we punctuate our writing rather than gnomonise it, and, in hindsight, I’m just a little bit sad about that.

In tenuously related news, a colleague forwarded me a link to an article penned by the BBC’s anonymous Vocabularist that looks at the names of punctuation marks through the ages. It’s a diverting little read. Gary Nunn’s recent Guardian article “If punctuation marks were people”, errs on the fictional side. As he writes with regard to the interrobang, for example,

- The interrobang is that inappropriate over-sharer we all know

- They ask you at work if you got laid at the weekend‽ Or if you’re hungover again today‽

Thank you to all the readers who send in links — if you have a punctuation-related story you’d like to see here, drop me a line!

- 1.

-

Brown, James. An English Syntithology in Three Books, Developing the Constructive Principles of the English Language, by Appropriate Polymorph Terms, Used in This Science Only, and Each Having But One Meaning. Philadelphia: H. Grubb, 1847.

- 2.

-

OED Online. “Gnomon”.

- 3.

-

York, Brantley. An Analytical, Illustrative, and Constructive Grammar of the English Language. Raleigh: Pomeroy, 1862.

- *

- Even if the latter practice is somewhat in decline. ↢

Comment posted by Bonnie on

I’m going to gnomonise a few of my essays with manicules this fall and see what my English professor thinks about that!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

As I hope many others do too. We’ll be gnomonising all over the place in no time.

Comment posted by Michael Anthony on

I gotta tell you, as an aspiring writer, this blog absolutely blows my mind with the coolest stuff on the planet. Wow! Keep up the good work.

For realsies, this comment may sound slightly sophomoric, but that’s exactly how I feel when I realize how little I know about the English language.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Michael — thank you very much! It’s very kind of you to say so, and I’m glad you like the blog.

Comment posted by Jeremy Wickins on

Fascinating as ever, Keith! Looking at Brown’s list, I realised that the ellipsis is an under-regarded punctuation mark (or gnomon, as I shall now have to annoy people with!) I don’t recall that you have covered it – is it on your to-do list?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jeremy — thanks! Glad you enjoyed the article. I haven’t written much about ellipses here, I’m afraid, but the Shady Characters book looks at them in a little more detail, specifically in their use as marks of elision or censorship.

Comment posted by Jamsheed on

I’m going to have to look at my copy tomorrow—because I was struck by the ellipsis as what looks like a long dash vs. what I would’ve expected: the three dots. And I don’t remember the discussion in the book!

And vague apologies for the slightly slapdash use of punctuation in this comment, but I do like being a little fast and loose with it sometimes :)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jamsheed — ah. Your comment made me take a second look at the image here, and yes, Brown has the ellipsis as a dash! Shady Characters talks about the two marks in tandem — both ‘…’ and ‘—’ were used to represent omitted words.

Comment posted by Ned Brooks on

Any idea why what looks like a sword, a dagger, or a cross is called “obelisk”?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ned — “obelisk” comes from the Greek obelus, meaning a spit or a sharpened stick. This is what the ancient Greeks called a particular dash-like mark they used in editing, and which ultimately evolved into the dagger we know today. The old name stuck, so to speak, for quite some time. There’s much more about this in the Shady Characters book!

Comment posted by Jon of Connecticut on

I like the image from the book. the letters and gnomons look warm and almost human compared to today’s letters and gnomons.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

They are! Coffee & Donatus has an even better image of the page in question.