Shady Characters: Ampersands, Interrobangs and Other Typographical Curiosities

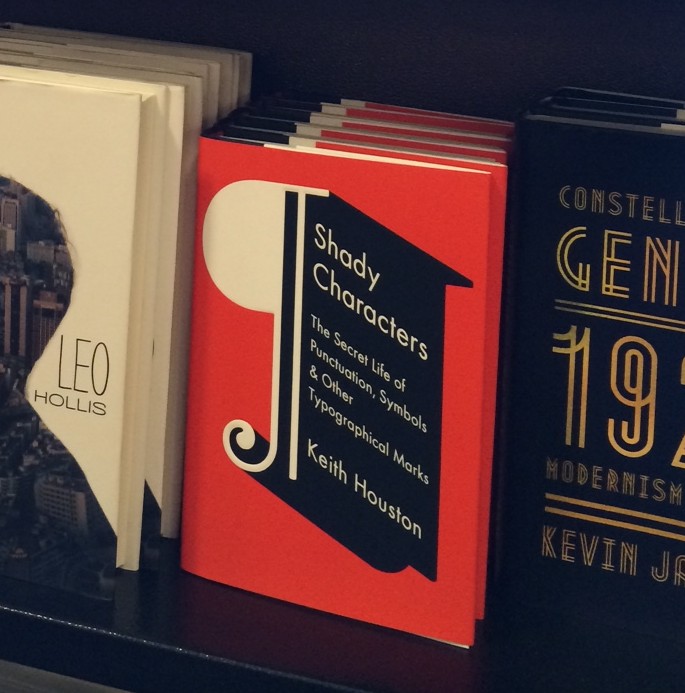

is now available in the UK. (I checked for myself at my local Waterstones and collected some documentary evidence, left. The recent excision of the Waterstone[’]s apostrophe still galls me.) You can order a hardback or digital copy from Amazon.co.uk, The Book Depository, Penguin, or Waterstones.

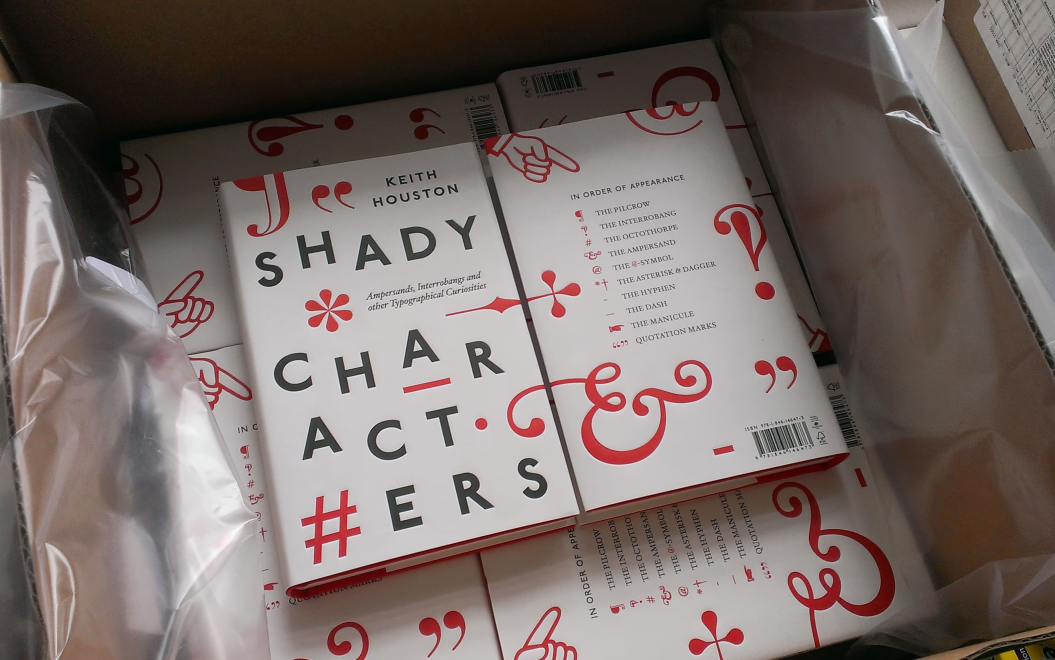

Thanks this time round go to Josephine Greywoode and Kate Watson at Particular Books, and cover designer Matthew Young, for all their hard work in bringing the UK edition to fruition!

As if a competition to win one of two copies of the UK edition isn’t enough, you can now also chance your hand at a copy of the American edition over at Constance Hale’s blog, Sin & Syntax. Good luck!