It’s easy to overlook the importance of empty space as a form of punctuation. Certainly, I’m guilty of giving pride of place to visible marks such as the pilcrow (¶) and interrobang (‽). But this isn’t to ignore the groundbreaking invention of the word space in the medieval period; the disappearance of the pilcrow to create the paragraph indent; or, most recently, the use of variable-length spaces as pauses in Patrick Stewart’s 2015 PhD thesis. Also recently, I was encouraged to look again at the subject of whitespace-as-punctuation by a visit to the Science Museum here in London.

First, though, it’s helpful to recap the 1200-year evolution of empty space as punctuation. Hold onto your hats.

For much of antiquity, texts were written in the traditional style of scriptio continua, or WORDSWITHOUTSPACES, that was favoured by the Greeks and Romans. Eventually, around the eighth century, Celtic monks at the fringes of what had once been the Roman Empire started to add spaces between words to ease the copying and reading of unfamiliar Latin texts.1 Later, with the arrival of printing in Europe in the fifteenth century, an exponential growth in the number of texts to be finished and bound led many printers to omit certain decorative flourishes that had once been added by hand — even as the whitespace dedicated to them continued to feature in printed works. Thus, the pilcrow and other paragraph marks, such as decorative initial caps, disappeared in favour of the now-familiar paragraph indent, as seen in this article.2

And so, by the end of the fifteenth century, the hierarchy of punctuation marks from the paragraph on down was essentially fixed. Paragraphs were separated by a newline followed by an indentation;* sentences were separated by one of a number of visual marks; clauses were separated by points, slashes, and other symbols; and words were separated by simple spaces.

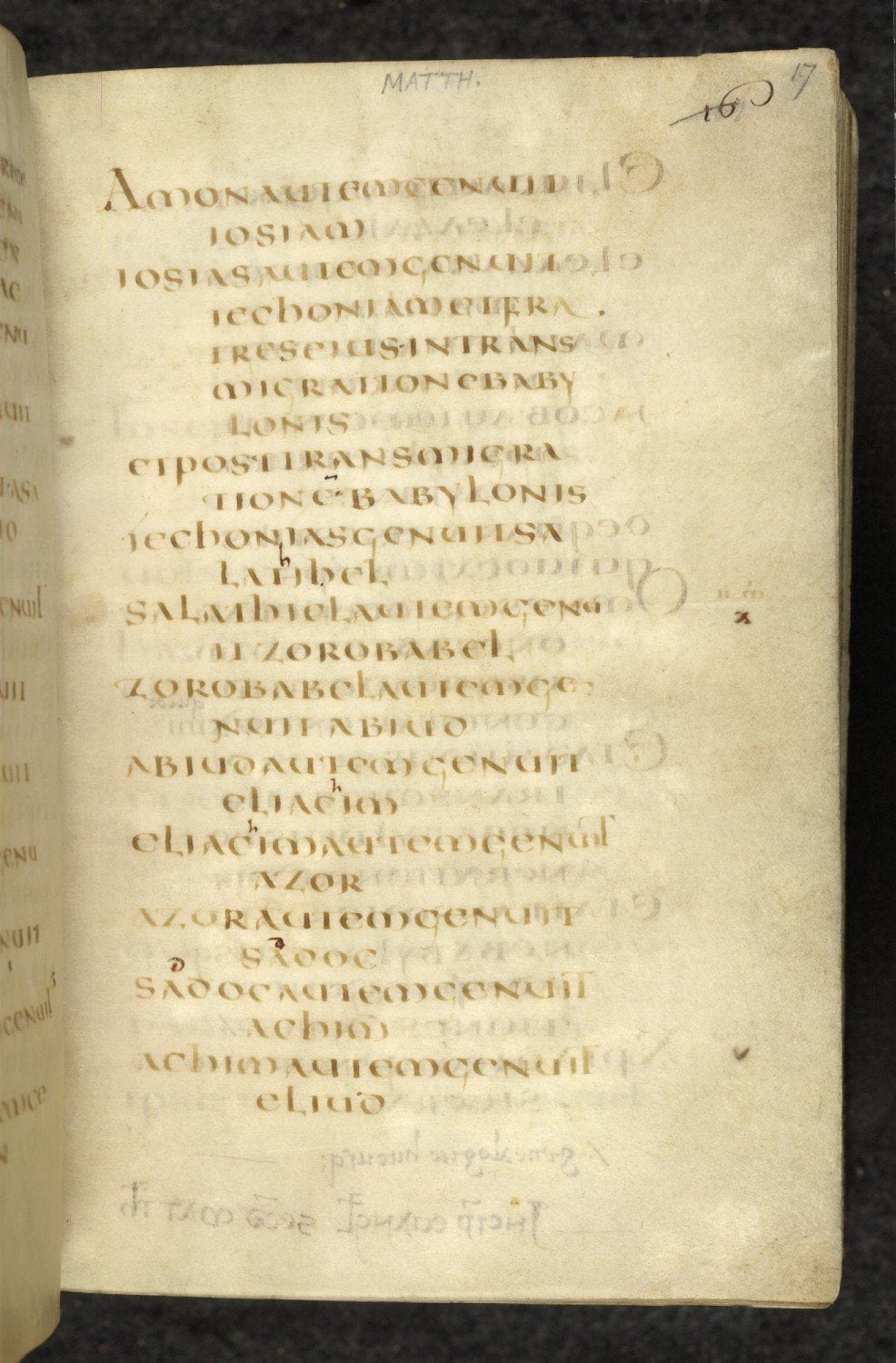

But that isn’t quite all there is to the story. Before the paragraph indent, before even the word space, some writers of the early Christian era experimented with a form of punctuation that they called per cola et commata — “by colons and commas”. Originating with St Jerome in the fourth century, texts arranged per cola et commata placed each sentence and clause on a new line. Where a clause was too long to fit on a single line, it was carried over the next line and indented to the right. 4 Here’s an example, from folio 17 of British Library manuscript Harley 1775, an Italian manuscript of the Four Gospels from the last quarter of the sixth century:

For those trained in the art of rhetoric, a comma was a short clause and a colon a longer one; together a sequence of commata and cola made up a complete periodos, or sentence. The prevailing method of punctuation would have been to add a middle (·), low (.) or high dot (˙) after each comma, colon and periodos respectively,5 but St Jerome, and those who followed his example, used page layout instead of visible marks to punctuate their texts. Given that punctuation began as a way for readers to insert spoken pauses in a written text, St Jerome’s innovative page layout makes a great deal of sense: here is an author inserting visible pauses in his writings to guide his readers in teasing apart their meaning.

All of this brings us to the Science Museum. I was there more or less by accident, killing some time with a friend, when we found ourselves in an exhibition called Churchill’s Scientists, about British scientific advances during WWII. As we wandered through it, I noticed a reproduction of a page from one of Winston Churchill’s speeches, and it looked mightily familiar.

It turns out that Churchill (or, perhaps, a secretary; I’m sure more knowledgeable readers will correct me) had a very particular way of laying out the notes for his speeches. You can see many examples of his typewritten notes at the Churchill Archive, but here are a couple of paragraphs from the closing section of his most famous speech, usually entitled “Their Finest Hour” from its last line, as an example:

If we can stand up to him,

all Europe may be freed,

and the life of the world

may move forward into

broad and sunlit uplands.

But if we fail,

then the whole world,

including the United States,

including all that we have known and

cared for,

will sink into the abyss of a

new Dark Age

made more sinister and

perhaps more protracted by

the lights of perverted

Science.

Now isn’t that striking? The notes for “Their Finest Hour” aren’t arranged strictly per cola et commata, for reasons I’ll come to in a moment, but the family resemblance is strong nonetheless. That resemblance becomes even more pronounced when you hear Churchill deliver this part of the speech, as in this British Pathé recording.† What you’ll notice is that when he pauses in his delivery, it is almost always at the end of a line. Only in the final lines of the second sentence above does he deviate noticeably from his per cola et commata-style layout, pausing after “protracted” and “lights”. Everywhere else, essentially, a new line signals a pause in his spoken performance.

Of course, if Churchill was aware of St Jerome’s fourth-century per cola et commata method (he was avowedly ambivalent toward Greek and Latin at school6), he did not follow it slavishly. His line breaks do not always fall where a comma, colon or semicolon might have been expected to appear. He has indented each line a little more than the last, rather than push them all to the left-hand margin, to make it easier to follow his notes as he read aloud from them. And, most obviously, the occasional stray comma has crept in, as if he could not quite bear to abandon conventional punctuation altogether.

Wherever Churchill found inspiration for his note-making technique, however, and whatever you think of the man himself, it’s difficult to argue with the results: his typewritten notes are weirdly lyrical in their layout and his speeches were undeniably effective. Per cola et commata or not, there’s a lot to be said for swapping commas, colons, and semicolons for the architectural precision of a new line of text.

- 1.

-

Saenger, Paul. “Silent Reading: Its Impact on Late Medieval Script and Society”. Viator: Medieval and Renaissance Studies, no. 13 (1982): 367-414.

- 2.

-

Haslam, Andrew. “Articulating Meaning: Paragraphs”. In Book Design, 73-74. Laurence King, 2006.

- 3.

-

Pamental, Jason. “The Life of ¶: The History of the Paragraph”. Print, no. Fall (2015).

- 4.

-

Parkes, M. B. “Antiquity: Aids for Inexperienced Readers and the Prehistory of Punctuation”. In Pause and Effect: Punctuation in the West, 9-19. University of California Press, 1993.

- 5.

-

Kemp, J Alan. “The Tekhne Grammatike of Dionysius Thrax: Translated into English”. Historiographia Linguistica 13, no. 2/3 (1986): 343-363.

- 6.

-

Churchill, Winston. “Harrow”. In A Roving Commission : My Early Life, 17. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930.

- *

- Writing in Print magazine, Jason Pamental hypothesises that the paragraph indent was joined by the blank line — another example of whitespace as punctuation — because of simple laziness. It’s easier, he writes, to hit the return key twice than it is to hit return a single time and then insert a tab or em quad at the start of the next line.3 ↢

- †

- The text above is modified slightly from Churchill’s original notes in order to match the speech as he delivered it. You can also read the “substantially verbatim” speech as it was transcribed by Hansard, the official parliamentary record, which differs again. ↢

Comment posted by Jeremy on

Churchill’s method of speech delivery – few words, pause, few more words, pause – drives me mad. I have never regarded Churchill as a particularly good speaker, though the content was excellent (let’s face it – it has been suggested that his awful delivery was a result of stammering, though it wasn’t).

In my opinion, the first paragraph of the speech quoted above would be much better as:

If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed, and the life of the world may move forward into broad and sunlit uplands.Unfortunately, so many people – especially politicians – think this is an effective speaking technique. Sadiq Khan did the same thing in his acceptance speech after the London Mayoral Election result last week. After three sentences, I screamed at the TV and turned it off. It is a method robotic and annoying, adding nothing to the content. If people are going to use breaks, then per cola et commata, so it makes some sort of grammatical sense.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jeremy — thanks for the comment! I’ve edited your example to match the typewriter-style used in the post. Is that a little better?

Comment posted by Jeremy on

Thanks, Keith – much better!

Comment posted by Graham Moss on

For more examples of spatial arrangement of text, you might take a look at how poetry in all its wide ranges is typeset, for starters Allan Ginsberg’s HOWL, and the way letterpress printers set lines too long for the measure.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Graham — that’s a good point! Michael Rosen suggested exactly the same thing when I talked to him for a Word of Mouth episode to be broadcast later this month.

Comment posted by Jeremy on

I was trying to remember what poem was brought to my mind by Keith’s article, and that’s the one! Thanks, Graham.

Comment posted by C on

You mention whitespace as appearing in the 8th century, if I read correctly. Hebrew manuscripts, going back way before that, have always had spaces between words and paragraphs. In fact, variations in the size of spaces between paragraphs in a Torah scroll are interpreted along with the text itself. I can’t include the picture, but you could see for yourself in this facsimile of a Torah scroll:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/88/Tikkun-Koreim-HB50656.pdf/page1-459px-Tikkun-Koreim-HB50656.pdf.jpg

The recurrent letter between paragraphs, פ , is a ‘p’ sound, which stands for ‘patuach’ meaning ‘open’. Sometimes there is an ס, or ‘s’, for ‘satum’ which means ‘closed’– a run-on paragraph. Till today, Torah scrolls are hand-written according to the same rules, which date back to the days of Moses.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi C — thanks for the comment! I’m hamstrung by my lack of knowledge of Hebrew and Hebrew texts, so I’m happy to be corrected. It’s interesting to see that Hebrew had its own capitulum-style paragraph separators in the form of the letters פ and ס.

Comment posted by Jeremy on

I don’t know why this topic (use of white space) has captured my imagination so much, but I find this fascinating. I think I have been baffled by the apparent inefficiency of the Roman scriptio continua – there must have been situations where confusion arose, but I assumed it was something to do with the development of writing. However, finding that at least one other written language (and in a Roman-occupied area) had spaces suggests something else was going on with the Latin writers. I have just had a very brief look at Sanskrit texts (nothing scientific), and there doesn’t seem to be regular use spaces there, either – and the older the text, the less likely spaces are to be found. Ancient Greek writing doesn’t seem to be big on spaces, either. These languages are linked, and so the reason seems to be that old habits died hard. An interesting question is whether Hebrew influenced the adoption of spaces – some of the scribes could well have been familiar with Hebrew texts, I suppose.

Ah, well, better get back to work …

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

It is fascinating, isn’t it? I haven’t come across any particularly convincing explanations at to why scriptio continua persisted for so long.

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

The Dead Sea Scrolls are 19–23 centuries old. Scroll through the Wikipedia article of that name and click on the images to enlarge them. The text was right-justified with ragged left margins (today’s hand-written Torah scrolls are justified on both margins).

Spaces were used to separate words (at least 600 years before the Celtic scribes). New paragraphs begin on a new line, sometimes with a blank line (no carriage-return laziness here — on the contrary, enough blank lines and you have used more of the expensive writing materals).

The handwriting is beautiful and easy to read (if you know Hebrew), in contrast with Medieval Greek and Latin manuscripts, which require special study to learn the letter shapes and abbreviations.

By the year 900, the scribes developed an elaborate system of punctuation marks — over 30 of them! Keith, you should read the Wikipedia article on Cantillation to get an idea of a punctuation system quite different from the modern European one.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

They are amazing to look at. If I might be permitted to blow my own trumpet, there’s a nice two-page image of the Ten Commandments in The Book!

Comment posted by Simon Smallwood on

A lot of the classical Latin texts which we see now are inscribed on stone, and for tombstones are also very formulaic, abbreviations abound, and they only had capitals to use. LETTERINGONSTONEWASEXPENSIVESOITMAKESSENSETOSHORTENWORDSANDJOINTHEMTOGETHERTOSAVESPACEONTRAJANSCOLUMN doesn’t it?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Absolutely! The question, then, is why did it last for so long in manuscripts?

Comment posted by Simon Smallwood on

It would be useful to study the use of Classical Latin in graffiti by the ordinary Roman citizens.

I can only think of Pompeii and possibly Ephesus for examples. There cannot be many actual manuscripts of the classical period for scholars to study. So graffiti on the walls of the public loos and brothels might show that words were more separated than we think.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Agreed. I took a few photographs of writing and inscriptions at Pompeii back in 2012 — the Romans were experimenting with dots·between·words at this point, but that fashion was forgotten not long after.

Comment posted by Walter Underwood on

Churchill’s speaking style is similar to that needed for speaking in a highly reverberant room, like a church or cathedral.

In parts of the room, the reflected, delayed sound is louder than the direct sound. You need to pause after every few words to let the reverberation die down. If you don’t the speech is unintelligible.

Cathedrals have reverberation times of 5-6 seconds. That is the time for the sound to die out (down 60 dB). A medium-sized church I know (All Saints, Palo Alto) has a 3.5 second reverberation sound.

It is possible that Churchill picked this up from listening in church services or from serving as a lector. That is where I learned to do it.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Walter — thanks for the insight! I wonder, then, if the architecture of the rooms in which he delivered speeches influenced the “architecture” of the text in his notes?

Comment posted by Walter Underwood on

It is possible. My dad typed his sermons double-spaced and marked them up for emphasis (underline, wavy underline). He might have used marks for pauses, too.

Comment posted by Jeremy on

Thank you, Walter. It is interesting that there might have been a practical reason for that type of delivery that has now been lost. It doesn’t excuse the modern perpetrators of the technique, though – how many of them speak in churches, especially without the use of audio circuits (which seem to reduce the problem you have mentioned)?

Comment posted by Walter Underwood on

This isn’t lost. It is a necessity in many places.

Sound reinforcement helps make speech more intelligible, but it doesn’t make the reverberations quieter. It just adds more direct sound.

Reverberation is necessary for pipe organs to sound good. They start and stop sounding abruptly. The reverberation covers the gaps and provides a natural swell on long notes. Without reverberation, pipe organs sound choppy, like a calliope.

Listen to the readings in the festival of nine lessons and carols from King’s College, Cambridge (2014).

Comment posted by Jeremy on

Thanks again, Walter. This is something I need to look at in more detail. It is probably a function of spending more time in modern lecture theatres and music venues than in churches (though I do love the sound of a good church organ).

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

I once had to speak in the Field House at a Midwestern university. This is a room large enough for a running track and a football pitch, with stands for the spectators (the house contained a field). I can assure you that if you spoke at your normal pace, you will be confused by the echo of your own words.

No doubt Churchill’s speaking style was honed in the House of Commons. What was the reverb time there in his day?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

That’s a good question, and one that Google Books seems unable to answer.

Comment posted by Ben Denckla on

It is perhaps interesting to note that some computer languages allow whitespace as an alternative to punctuation, notably the Python and Haskell languages. In particular, indentation is used to group lines together underneath some sort of heading element such as a function declaration or “if” statement. The more traditional way to express such a grouping is with some sort of brackets, often curly (squiggly) brackets (braces). In fact Haskell still allows such explicit grouping to be used if it is desired (or for some reason required) instead of indentation-based grouping.

The wisdom of these features, like all programming language features, are hotly debated.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

I struggle with Python’s whitespace-driven scoping. It’s easy to break, I find, since the indentation of each line in a block has to be formed of exactly the same characters: four spaces are not the same as a tab, for example, even if visually there’s no distinction. I understand that scoping isn’t always easy to understand, but it feels like hiding complexity rather than addressing it directly.

So yes, a subject for debate! Thanks for the comment.

Comment posted by Walter Underwood on

Re: Python and white space.

When I first started programming in Python in 1996, I was worried about using indentation for block structure. Nine years later, with a lot of production Python code under the bridge, I could attribute a single bug to an indentation mistake. So I learned to stop worrying and love indentation.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Walter — I’ve only ever dabbled in Python, and my problems with spaces for scoping are more philosophical one than practical. I just can’t quite bring myself to make peace with a feature that seems almost wilfully designed to confuse newbies. I’ll have to defer to you on this one — perhaps it isn’t as bad as all that.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by Walter Underwood on

Switching to an indentation-block language really is scary at first, but I got the hang of it quickly. These days, braces are annoying because they chew up vertical white space unnecessarily.

Since our focus is history, I think the first computer language to use indentation for block structure was Occam (1983), mostly used on the Transputer.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam_(programming_language)

One could certainly argue for one-level indented blocks in Make (application compilation language) and lex and yacc (a lexical analyzer and compiler generator). Both were released in 1975, if I remember correctly.

Comment posted by Ben Denckla on

BTW, one of the earliest proposals for letting indentation have semantics is ISWIM in Peter Landin’s 1966 “The Next 700 Programming Languages”: http://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/epl/Landin66.pdf

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Walter, Ben — two interesting bits of computing history there to look into! Thanks for all your comments on this.

Comment posted by Ben Denckla on

I have recently run across a book that directly addresses an ambiguity that has frequently challenged me in re-setting poetry:

I’ve retained the line breaks in the original since it is somewhat curiously set ragged-right at well less than the full width, possibly indicating a conscious choice of line breaks. I.e. this is a quasi-poetic comment on the book’s setting of poetry. (Meta-poetry?) This comment is all that appears on a verso in the front matter, by the way.

This is from the 1979 (first) edition of Stephen Mitchell’s Into the Whirlwind: A Translation of the Book of Job.

The ambiguity is due to the use of vertical whitespace to delimit stanzas (or what are here referred to as “verse paragraphs”).

This is rather analogous to the ambiguity between hard and soft hyphen, a problem I have raised elsewhere in comments on this blog.

The ambiguity here is between hard and soft vertical space, if you’ll permit the coinage. I.e. between vertical space that needs to be present always (hard), vs. vertical space introduced only because of the need for a page break (soft).

Hyphens are to line breaks what vertical spaces are to page breaks.

Comment posted by Ben Denckla on

Woops I guess <br> was not allowed so I did not retain the line breaks in the original in my blockquote. In fact this has caused the words before and after the break to run together, forming “pageindicates” and “paragraphbegins”!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ben — it looks like a closing slash is required, like this: <br/>. I’ve updated your comment accordingly!

The use of whitespace to delineate paragraphs is much more suited to continuous media, such as web pages. If you absolutely must start a paragraph on the first line of a new page in a paginated medium such as a book, an indent will do so without ambiguity.

Thanks for the comment!