The irony marks proposed by John Wilkins, Alcanter de Brahm and Hervé Bazin proved stubbornly resistant to putting down roots, and Bazin’s 1966 point d’ironie would be the last to be publicly promoted for some decades. Before the Internet reinvigorated their cause, though, the hunt for a foolproof method of conveying verbal irony took an abrupt detour: if a self-contained irony mark was not enough, perhaps an entire alphabet was the answer. And whereas the concept of an irony mark had exerted a strange pull on a select few French writers, the idea of signalling verbal irony with a different typeface altogether was instead the preserve of English-language journalists.

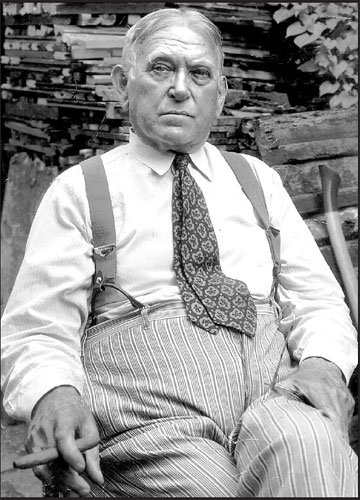

In 2005 The Baltimore Sun, newspaper of record in the state of Maryland, underwent a comprehensive redesign. Every aspect of its visual design was revisited: its layout and masthead were changed, pictures were given pride of place, and a new typeface was commissioned from the French typographer Jean François Porchez.1 Named ‘Mencken’ in honour of the Sun’s most famous writer, the iconoclastic H.L. Mencken, Porchez elaborated on the choice of name:

According to the London Daily Mail, H.L. Mencken even ventured beyond the typewriter and into the world of typography. Because he felt Americans did not recognize irony when they read it, he proposed creation of a special typeface to be called ironics, with the text slanting the opposite direction from italic type, to indicate that the writer was trying to be funny.2

Christened Henry Louis, the young Mencken adopted ‘H.L.’ after his father broke the lowercase ‘r’ letterpunches of a toy printing set one Christmas morning.3 An editorialist for the Sun during the first half of the 20th century, Mencken was “a humorist by instinct and a superb craftsman by temperament [with] a style flexible, fancy-free, ribald, and always beautifully lucid.”4 An avowed elitist who expressed amused contempt at the levelling tendencies of democracy, the so-called Sage of Baltimore did not have a high opinion of the common American. In 1926, for instance, he wrote:

No one in this world, so far as I know — and I have researched the records for years, and employed agents to help me — has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people. Nor has anyone ever lost public office thereby.5

Mencken’s suggestion of ‘ironics’ seems entirely in keeping with his evident dry wit but there is, however, a catch. As with everything in journalism, attribution is key, and in this case it is notably absent. Following Jean François Porchez’s reference to the Daily Mail leads to a pair of articles written by that paper’s columnist Keith Waterhouse, in each of which he makes a brief mention of Mencken’s supposed invention. First, in 2003:

Americans do not do irony.

Their language guru H. L. Mencken once proposed a special typeface to be called ironics, facing the opposite way from italics, to indicate that the writer was trying to be funny.6

And later, in 2006:

Irony has always been a headache for writers of wit who have to explain to readers of little wit that they were being ironic. The problem was solved by the great American journalist H. L. Mencken who invented a typeface sloping the opposite way to italics and called it Ironics.7

Waterhouse is certainly a credible authority on the English language, having penned the Daily Mirror’s in-house style guide — later published as Waterhouse on Newspaper Style8 — and also the purpose-written sequel English Our English: And How to Sing it.9 His articles, though, mark both the beginning and end of the trail, and if Waterhouse was privy to some incontrovertible evidence that Mencken was the creator of the term ‘ironics’ then he took it with him to the grave in September 2009.10

Who, then, did create ironics? Mencken here is joined by a later 20th century newspaperman, this time the columnist and reviewer Bernard Levin. A 2008 article entitled “Ha ha hard”, published in Levin’s old paper The Times, began:

Humour is a funny thing. Or sometimes it’s not. It’s certainly an easily misunderstood thing. The late, great Bernard Levin used to say that The Times should have a typeface called “ironics” to warn his more poker-faced readers when he wasn’t being serious.11

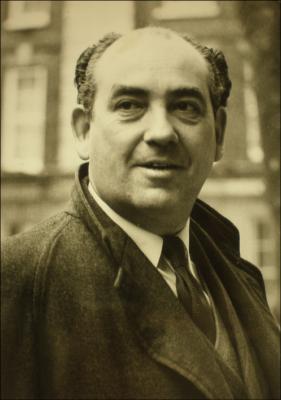

Bernard Levin was similar to H.L. Mencken in many ways: prodigiously talented, prodigiously opinionated and loyal to a single newspaper for much of his career.12 Also like Mencken, Levin is an enticing candidate for having created the idea of an entire alphabet dedicated to irony, but again the truth is uncooperative in this regard. Rather than having invented ironics, it seems that he was instead the first journalist to bring them to light. In a 1982 column for The Times, Levin identified not himself but a certain Tom Driberg as their creator:

Much of my time is spent trying to dispel the belief that my words mean the exact opposite of what they say, such an assurance being necessary in view of the apparently unshakeable determination among many readers to misunderstand them.

As for trying to be funny — well, long ago the late Tom Driberg proposed that typographers should design a new face, which would slope the opposite from italics, and would be called “ironics”. In this type-face jokes would be set, and no-one would have any excuse for failing to see them. Until this happy development takes place, I am left with the only really useful thing journalism has taught me: that there is no joke so obvious that some bloody fool won’t miss the point.13,*

Clearly, Levin shared Mencken’s dim view of the relative wit of the common people.

That this Tom Driberg — not H.L. Mencken or indeed Bernard Levin — was the originator of ironics was seconded by Brooke Crutchley, one-time head of Cambridge University Press. In a 1994 letter to The Independent, Crutchley wrote:

The late Tom Driberg had an idea for avoiding such misunderstandings, namely, the use of a typeface slanted the opposite way to italics. He suggested it should be known as ‘ironics’.15

So much as is possible within a newspaper’s letters pages and editorial columns, here was independent confirmation of Driberg as inventor of ironics.

Compared even to such iconic journalists and renowned personalities as H.L. Mencken and Bernard Levin, the Right Honourable Baron Bradwell PC of Bradwell-juxta-mare, né Thomas Edward Neil Driberg MP, alias William Hickey, codename Lepage, led the very definition of a colourful life.

Born in 1905 in Crowborough, Sussex, son of a former officer of the Indian civil service, Tom Driberg began parallel journalistic and political careers at the age of 19 when he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain at Oxford. Cutting his teeth on the party’s in-house Sunday Worker, he graduated to the widely-read Daily Express in 1933, writing a society gossip column called “These Names Make News” under the pen name William Hickey.

With the arrival of the Second World War, Driberg’s political aspirations came to the fore. Recruited by Britain’s internal security service to spy on subversives within the Communist Party, his cover was blown by the Russian mole Anthony Blunt and he was summarily ejected from the party. This proved to be a mere speed-bump on the road to political prominence, though his rise was not without cost: elected to the House of Commons in 1942 as the independent Member of Parliament for Maldon, Driberg was fired from the Express over a perceived conflict of interest with his parliametary duties. Although he subsequently wrote occasional pieces for the Daily Mail and New Statesman, his career as a working journalist would never quite recover.

Switching allegiance to the Labour Party before the 1945 election, Driberg retained his seat in Maldon; in 1957 and 1958 he held the post of Chairman of the Labour Party; in 1965 he ascended to the heights of the Privy Council, a body that advises the British Sovereign in exercising their powers, and ultimately he was created Baron Bradwell just a year before his death in 1976.16

Barring a few youthful misadventures, it seemed as though Tom Driberg had led a distinguished and fruitful career.

Upon Driberg’s death, though, fissures started to appear in his mostly respectable public image. First, his lifelong homosexuality, already an imperfectly kept secret that had only narrowly avoided the front pages on a number of occasions, was revealed in his obituary in The Times.17 It was the first posthumous outing of a public figure in the paper’s history.18 Soon after, Driberg’s unfinished memoirs were published, gleefully detailing his incorrigible pursuit of anonymous sexual encounters and a decided preference for public conveniences as their favoured venue.19 Legend has it that many of his Westminster contemporaries heaved a sigh of relief when it became apparent that upon his death, Tom had only got as far as 1942, before his parliamentary career — and conquests — had begun.

Later still, the 1992 defection of KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin brought files detailing a 1956 visit to Moscow, where, true to form, Driberg had fallen victim to a honey-trap operation set for him in the urinals behind Moscow’s Metropole hotel. Thus encouraged into service by the Russian spy agency, he was given the codename Lepage20 and assigned a Czech handler to whom he delivered secret information in exchange for money. Lepage, however, turned out to be a less than useful asset; the information he passed on consisted less of state secrets than the sexual preferences of various Labour Party mandarins.

Perhaps most triumphantly absurd of all, a 1989 biography of the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley, the self-proclaimed ‘Great Beast 666’ and ‘wickedest man in the world’,21 revealed that in 1925 Crowley had anointed Tom Driberg as his chosen successor. Crowley habitually tapped the rich, educated and gay for his disciples and Tom Driberg certainly gave the appearance of being all three. Ultimately, though, it was the perpetually broke Driberg who took financial advantage of Crowley: obtaining one of Crowley’s diaries through underhand means, he sold it to Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page in 1973 for “a handsome sum” with which he paid off some debts.22 Aleister Crowley never made good on his promise to his chosen successor, and Driberg did not pursue it, but the revelation made for a fittingly preposterous bookend to an extraordinary life story.

And of course, somewhere in amongst his activities as a Member of Parliament, an occultist, a Communist, a British spy, a Russian spy, a frequenter of public toilets, and a Peer of the Realm, Tom Driberg made a possibly apocryphal remark proposing the creation of a typeface in which jokes would be set, which would be slanted the opposite way from italics, and that would be called ‘ironics’.

Sadly, despite their impressively multifarious pedigree, ironics never made it into print, and the players in this typographic drama (or satire?) — Mencken, Waterhouse, Levin, Crutchley and Driberg — are all now gone. However ingenious their creation, and however valuable their contribution to written English might have been, the characters of written irony remain resolutely upright. Most ironically of all, Jean François Porchez’s font ‘Mencken’, named for one of the supposed creators of ironics, stuck most conservatively to roman, italic and bold typefaces with neither an ironic character nor an irony mark in sight.

- 1.

-

“A New Style”. The Baltimore Sun, August 2011.

- 2.

-

Porchez, Jean François. “Mencken Text”. Porchez Typofonderie, August 28, 2011.

- 3.

-

Kelly, Jacques. “H.L. Mencken, Pioneer Journalist”. The Baltimore Sun.

- 4.

-

Mencken, H L, and A Cooke. “An Introduction to H. L. Mencken”. In The Vintage Mencken, xi+. Vintage Books, 1955.

- 5.

-

Mencken, H L. “Notes on Journalism”. Chicago, Illinois, September 1926.

- 6.

-

Waterhouse, Keith. “Terror Betting for Guys and Dolls”. Daily Mail.

- 7.

-

Waterhouse, Keith. “{Smoke Gets in Your Eyes and up Their Noses}”. Daily Mail.

- 8.

-

Waterhouse, Keith. Waterhouse on Newspaper Style. Viking, 1989.

- 9.

-

Waterhouse, K. English Our English: And How to Sing It. Penguin Books, 1994.

- 10.

-

Molloy, Mike. “Keith Waterhouse”. The Guardian.

- 11.

-

Morrison, Richard. “Ha Ha Hard”. London: Times Newspapers Ltd, January 2008.

- 12.

-

The Times. “Bernard Levin”.

- 13.

-

Levin, Bernard. “Untitled”. London: Times Newspapers Ltd, February 1982.

- 14.

-

Saunders, Frances Stonor. “How the CIA Plotted Against Us”. New Statesman.

- 15.

-

Crutchley, Brooke. “Letter: Visual Rhetoric”. The Independent.

- 16.

-

Wheen, F. Tom Driberg: His Life and Indiscretions. Chatto & Windus, 1990.

- 17.

-

The Times. “Lord Bradwell”. August 13, 1976.

- 18.

-

Hitchens, Christopher. “Reader, He Married Her”. London Review of Books 12, no. 9 (May 10, 1990): 6-8.

- 19.

-

Driberg, T. Ruling Passions. Cape, 1977.

- 20.

-

Assinder, Nick. “Driberg Always under Suspicion”. BBC News.

- 21.

-

Symonds, J. “The King of the Shadow Realm: Aleister Crowley, His Life and Magic”. In The King of the Shadow Realm: Aleister Crowley, His Life and Magic, 407-415. Duckworth, 1989.

- 22.

-

Hutchison, Roger. “Aleister Crowley Has Been Dead 50 Years. But we’re Still under His Spell”. The Scotsman. May 11, 1999.

- *

- Levin’s column about ironics was also published by Encounter, a British literary and cultural journal that ran from 1953 to 1991, and which is worthy of a digression all of its own. Encounter had the bizarre distinction of having being set up and covertly funded by the USA’s Central Intelligence Agency and the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service, with the aim of making up for the lack of anti-communist rhetoric emanating from the popular — and left-wing — New Statesman. Its CIA funding became public knowledge in 1967, prompting the resignation of its editor and co-founder Stephen Spender (coincidentally, an Oxford contemporary of Tom Driberg), who claimed to have known nothing about the identity of his backers.14 ↢

Comment posted by Jason on

I am perpetually impressed with the technical quality of the writing–you excellently begin, end, and maintain exquisite pacing in each of your articles, and this one was no exception. Thank you for writing these, they always brighten my weekends!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Jason — thanks! Very kind of you to say so, and I’m glad you’re enjoying the articles.

Comment posted by Richard Polt on

Another fascinating story! Shady characters, indeed …

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Richard — thanks! I must admit, I really enjoyed writing this article. The people behind the various symbols I’ve looked at are at least as interesting as the marks themselves, though Tom Driberg really does takes the cake.

Comment posted by Adam Rice on

Fascinating. I’ve occasionally seen reverse-italics on headstones dating from the 1800s, but I’m confident they’re not being used in a tongue-in-cheek manner.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Adam — that’s an interesting tidbit. Do you happen to have any references or images of this use of backwards-slanting text?

Comment posted by Alan Kriegel on

Look up backslope and backslant (sometimes hyphenated). This was realitvely common during that time due to all of the exploration. However, it isn’t pretty.

As always, top-notch article.

Comment posted by Kathleen on

Fascinating biographies! Thanks!

It does seem that the idea of “ironics” is fun but unnecessary: it would encourage both authors and readers to become a little lazy, wouldn’t it? After all, great satirists like Jane Austen, or W.M. Thackeray, or Christopher Hitchens, tend to get laughs in the right place given a sharp enough audience. It’s a good way to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Then again, Mencken (if it was him) knew that very well when he proposed the idea, didn’t he? ;-) And so: the idea of ironics is itself…ironic! Genius!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Kathleen,

Thanks for the comment! You’re quite right, and the layers of irony implied by both the invention and use of ironics just keep on peeling back like the skin of an onion. I think the reason for the general failure to stick of any sort of irony punctuation is pretty self-evident!

Comment posted by Kathleen on

Looking forward to seeing your implementation of the backward slanting italics in future posts. :-)

Comment posted by andrew wilson lambeth on

another wonderfully elegant and engrossing chapter, keith . i was thinking of another way to track the origin of the ironics witticism—by imaginative reconstruction . let’s suppose that the remark was first made by a newspaper journalist talking to a print compositor ( and then, of course, much repeated at various long boozy lunches, for which newspaper journalists are famous ) . i suggest this because the printing types available to a twentieth-century newspaper ( the times excepted ) were of two, and generally only two, classes : the headliners and the ionics . ionics as a category of types were named after ionic no5, the grandaddy of specialist newspaper types . a marketing tradition developed to call all such fonts by fancy classical names : excelsior, paragon, corona, volta, nimrod, etc, followed . so, to this hypothetical newspaper printer, all his text fonts were ionics . how likely then that if a journalist were to go downstairs and ask any rudimentary question, he would hear the term, or even mis-hear it, and make his witticism about never mind ionics, what he needed was ‘ironics’, to assist the dimwits who read the damned rag to get his subtler humourisms ? actually, it would be an unusual journalist who bothered to speak shop to lowly compositors—the big london papers had vast, intensely unionized printworks, off-bounds to journalists, and the two professions frequented different eating and drinking houses on fleet street . but on the other hand, any journalist with a fancy for ‘rough trade’ may well have found himself bridging that social gap ( perhaps i need some backslanted italics in that last phrase )

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Andrew — what an enticing idea! His biography and autobiography would tend to suggest that if there was ever a journalist likely to mingle with the rougher elements of Fleet Street’s workforce, it was Tom Driberg. I may have to add a reference to ‘ionics’ to any future versions of this article…