So: you’ve made some paper, and now you need to put something on it. Some text would be nice, but what about illustrations? For a thousand years, first in China and later in the West, the best way to do just that was to make a woodcut print — to carve out an image on a wooden block, apply ink, and press it onto the page.

Woodcut was the perfect match for the lead soldiers of movable type. The carven image was embossed on the wood, just as the letters were embossed on the type, and so the two could be locked up together to make a single “forme”, or printing surface, for each page. (Later printing methods, such as copperplate engraving, required text and images to be printed separately.) Moreover, wood blocks could be cut into any shape or size to facilitate more creative page layout — as in the page shown above, where the image of Christ on the cross would have been carved onto a T-shaped block to leave room for a column of text to either side. Perhaps most important of all, wood was a forgiving medium: plentiful, easy to carve, and simple to repair with a dowel or plug in case of a mistake.

That’s the theory, at least. But what about the practice? Back in 2014, in the course of writing The Book, I got the chance to find out when a friend introduced me to Liz K. Miller, a printmaker working at the Lavender Print School in Battersea, London, and who helped me try my hand at making a woodcut print of my own.

When I arrived one day in June of that year, Liz showed me into the bright, white, airy studio where she was helping a class of students prepare for an upcoming exhibition. For me, more accustomed to a mid-1950s library pierced only by a few wan skylights, it was like stepping into the open air. The walls were hung with finished prints and many more dangled from drying racks hung from the roof. Liz presented me with a block of wood about the size of an A5 sheet of paper and asked me to draw out the design I wanted to print.

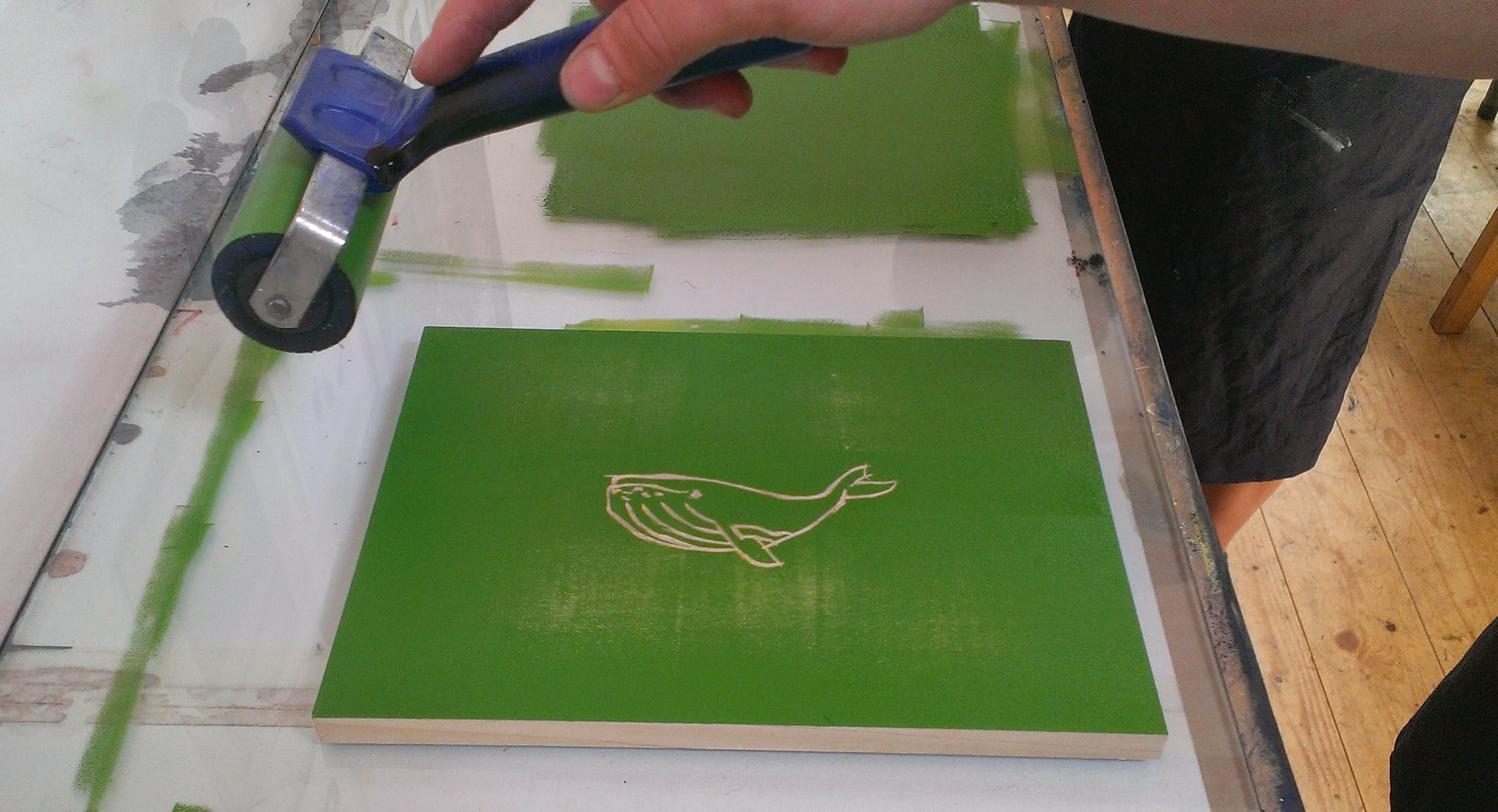

Now I am not, nor have I ever been, an artist. A compromise was reached: I’d find a design I liked, trace it using a wax crayon, then burnish the tracing onto the wooden block. I flipped through some of the studio’s sample books and chose a simple image of a friendly baleen whale, as you can see below.*

Eat your heart out, Dürer.

The next step was to carve the design into the wood itself using the set of metal-tipped wood-carving tools you can see here. These came from Japan, which, like China, has a robust tradition of woodcut printing. The tool I chose had a U-shaped blade designed to remove wood from the surface of the block when run across it at a shallow angle — a sort of ice-cream scoop for wood.

Liz encouraged me to try carving a few lines on the back of the block. “It’s almost like butter,” she said, and after some experimentation I could start to see what she meant. I might qualify her statement to say that wood is like butter only with tighter tolerances: Get the angle of the tool right and it tills the surface with ease, carving out a springy curl of wood. Too shallow and it skates over the surface of the block; too deep and it catches and beds in. It was a tricky process but rewarding when it worked.

It’s worth nothing that the woodcutter who created the image at the top of the page carved out all the non-printing areas — only the black, printed lines were left raised above the surface — as was typical of most woodcut illustrations of the time. In my case, in the interests of saving some time I carved out only the lines of my design, creating an intaglio, or inset print. This was the result:

And so, after a surprisingly short amount of time, we were ready to print the image. Liz rolled some oil-based ink onto the surface of the block; I laid a piece of paper on top of it and used a soft pad to press the paper down onto the inked block, and then peeled off the paper. We were finished!

Our first print was a little uneven but the second, which you can see below, was much better. Liz kept the block and the first print for demonstration purposes (a compliment or a warning to future students? I couldn’t tell) and I proudly brought home the second.

As with my attempts at making paper, I came away from my day at the print school with a considerable amount of respect for the craftspeople who made (and who still make) books in the traditional manner. Woodcut printing today may be more closely associated with art than with bookmaking, but the fact remains that the world of books once leaned on it heavily: for many centuries woodcut was an equal partner of movable type, and books were all the better for it.

Many thanks to Liz Miller for guiding me through the process of making my print, for answering all my questions, and for buying me a coffee from the roving barista who took orders from thirsty artists. Liz is no longer at Lavender Print School (she has just completed a three-year Print Fellowship at the Royal Academy Schools), but you can learn more about her work at her website or at her Facebook page. There are more pictures from my day at Lavender in this album at Google Photos.

Lastly, if you’ve enjoyed this article, why not buy a copy of The Book? It examines the invention of woodcut printing, its journey to the West courtesy of Marco Polo and his contemporaries, and much more besides. The Book will be published in both the UK and the USA in August 2016.

- *

- Sadly, there were no sperm whales to be found. ↢