I wrote the following post for The Future of Text, a collection of essays exploring the past, present and future of text in all its many forms. It forms a kind of introduction to, or perhaps a summary of, the contents of my series on emoji. Some of it will be familiar if you’ve been following along, and some of it may not. Either way, enjoy, and please read to the end for more details on The Future of Text, including where to download a copy.

It started with a heart, so the story goes. Emoji’s founding myth tells that telecoms operator NTT DOCOMO, at the height of Japan’s pager boom of the 1990s, removed a popular ‘♥️’ icon from their pagers to make room for business-oriented symbols such as kanji and the Latin alphabet. Stung by a backlash from their customers, in 1999 NTT invented emoji as compensation, and the rest is history.

Only, not quite. It is true that in 1999, NTT used emoji to jazz up their nascent mobile internet service, but emoji had been created some years earlier by a rival mobile network. It was only in 2019, twenty years after emoji’s supposed birth at NTT, that the truth came out.

Does it matter, when considering the structure and transmission of text, that for two decades our understanding of emoji’s history was wrong? Safe to say that it does not, but it serves as a salutary reminder for those who care about such things that emoji are slippery customers. And now, having colonised SMS messages and social media, blogs and books, court filings and comic books, these uniquely challenging characters can no longer be ignored.

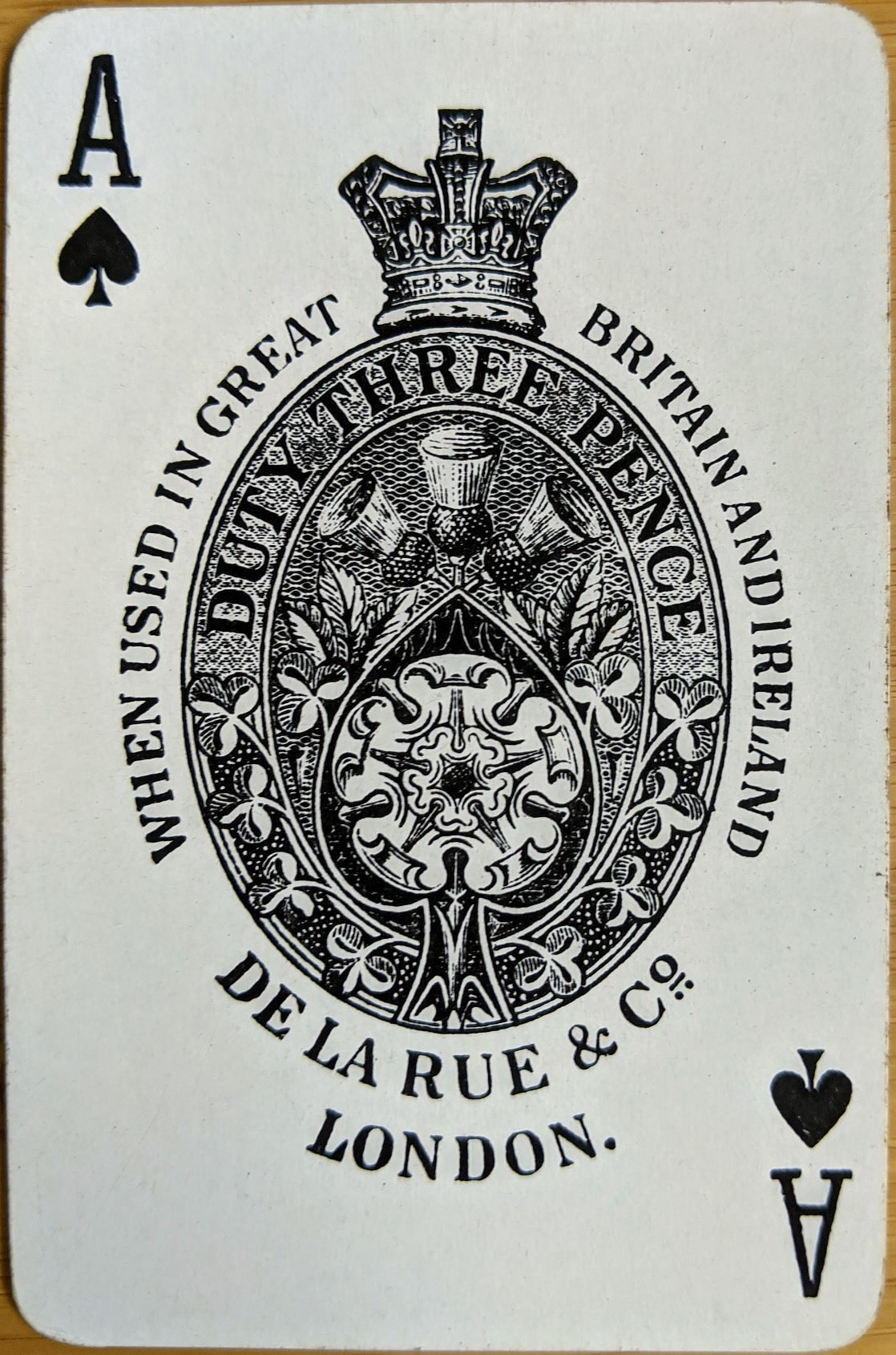

As with essentially all modern digital text encodings, emoji lie within the purview of the Unicode Consortium. Almost by accident, what was once a head-down, unhurried organisation now finds itself to be responsible for one of the most visible symbols of online discourse. And, unlike the scripts with which Unicode has traditionally concerned itself, emoji are positively alive with change. Almost from the very beginning – that being 2007, when Google and Unicode standardised Japan’s divergent emoji sets for use in Gmail – Unicode has been on the receiving end of countless requests for new emoji, or variations on existing symbols. (Of note has been a commendable and ongoing drive to improve emoji’s representation of gender, ethnicity and religious practices.) Thus “emoji season” was born, that time of the year when Unicode’s annual update has journalists and bloggers scouring code charts for new emoji.

And therein lies a problem: emoji updates are so frequent, and so comprehensive, that it is by no means certain that the reader of any given digital text possesses a device that can render it faithfully. The appearance of placeholder characters – ‘☒’, colloquially called “tofu” – is not uncommon, especially in the wake of emoji season as computing devices await software upgrades to bring them up to date. Smartphones, which rely on the generosity of their manufacturers for such updates, are worst off: a typical smartphone will fall off the upgrade wagon two or three years after it first goes on sale, so that there is a long tail of devices that are perpetually stranded in bygone emoji worlds.

If missing emoji are at least obvious to the reader, the problem of misleading emoji is not. Although Unicode defines code points for all emoji, the consortium does not specify a standard visual appearance for them. It suggests, yes, but it does not insist. As such, Google, Apple, Facebook and other emoji vendors have each crafted their own interpretations of Unicode’s sample symbols, but those interpretations do not always agree. As such, in choosing an emoji, the writer of a text may inadvertently select a quite different icon than the one that is ultimately displayed to their correspondent.

Consider the pistol emoji (🔫), which, at different times and on different platforms, has been displayed as a modern handgun, a flintlock pistol, and a sci-fi ray-gun. (Only now is a consensus emerging that a harmless water pistol is the most appropriate design.) Or that for many years, smartphones running Google’s Android operating system displayed the “yellow heart” emoji (💛) as a hairy pink heart — the result of a radical misinterpretation of Unicode’s halftone exemplar — that was at odds with every other vendor’s design.

These are isolated cases, to be sure, but it is perhaps more concerning that Samsung, undisputed champion of the smartphone market, once took emoji noncomformity to new height. Prior to its most recent operating system update, Samsung’s emoji keyboards sported purple owls, rather than the brown species native to other devices (🦉); savoury crackers rather than sweet cookies (🍪); Korean flags rather than Japanese (🎌); and many other idiosyncrasies.

Today, most vendors are gradually harmonising their respective emoji, while still preserving their individual styles. (Samsung, too, has toned down its more outlandish deviations from the norm.) But although the likelihood of misunderstandings is diminished, it is still impossible to be sure that reader and writer are on the same page: with emoji, the medium may yet betray the message.

Finally, and as absurd as it sounds, is the prospect of emoji censorship. From 2016 to 2019, for example, Samsung devices did not display the Latin cross (✝️) or the star and crescent (☪️). These omissions had mundane technical explanations, but it is not difficult to imagine more sinister motives for suppressing such culturally significant symbols. In fact, one need not look far to find a genuinely troubling case. Starting in 2017, Apple modified its iOS software at China’s behest so that devices sold on mainland China would not display the Taiwanese flag emoji (🇹🇼). At the time of writing, as protests against Chinese rule rock Hong Kong, ‘🇹🇼’ has disappeared from onscreen keyboards there, too.

In this there are echoes of Amazon’s notorious deletion of George Orwell’s 1984 from some users’ Kindles because of a copyright dispute. A missing emoji might seem like small fry by comparison, but it is every bit as Orwellian: is a text written in this time of crisis devoid of Taiwanese flags because the writer did not use that emoji, or because it had been withheld from them? The case of the missing ‘🇹🇼’ shows how emoji, often derided as a frivolous distraction from “real” writing, can be every bit as vital as our letters and words. We owe it to them to treat them with respect.

The Future of Text, edited by Frode Hegland, is, in his words, “the first survey of the possible futures of text”. That sounds grand, but there’s substance to back it up: Frode has run the Future of Text symposium since 2011, at which luminaries such as Vint Cerf and Dame Wendy Hall often speak. This year is the first in which the symposium is accompanied by a book, which you can find and download here.