Things are busy here at Shady Characters and I’m afraid there’s no time for a proper entry this weekend. What I can offer you instead is the brief history of the # and the @ that I put together recently for the Penguin Books blog — have a read, and feel free to drop by afterwards with any comments you might have!

Miscellany № 61: verbal irony seeks meaningful relationship. No, really.

Well, hello there.

You all know the handsome fellow that adorns the cover of this book, don’t you? This is the ironieteken, the brainchild of type designer Bas Jacobs, and it is used to terminate an ironic statement.1 Specifically, it is intended to punctuate verbal irony, where a speaker or writer says one thing but means another. It is, to my mind, the most visually convincing irony mark to date — but for the purposes of today’s short post, it is merely one of the many suitors who have tried and failed to win irony’s hand in marriage.

After posting last year about the quasiquote (still one of my favourite finds!), a New Zealand reader named Kim Anderson got in touch to tell me about a typographic design project she was about to embark upon. And though the subject of her project has since morphed from the quasiquote to the irony mark, it is my pleasure to share it with you now that it is finished. As Kim describes it:

For centuries a quiet but persistent debate has raged over whether irony should be punctuated. Many have put forward their suggestions for an irony mark (all with varying degrees of seriousness), but so far none have lasted the test of time.

Fascinated by this topic, I styled the search for an irony mark into irony’s search for a punctuation soulmate — its perfect match. While many obstacles stand in irony’s way to find true punctuated love, it perseveres right into the digital age.

Kim took to heart the idea that irony has been seeking a typographic partner since, oh, the time of the Great Fire of London, and produced a book chronicling its quest to find the right irony mark through posting in a lonely hearts column. The ironieteken you see above is the cover star of the resultant book, titled Unpunctuated seeking and written, designed, printed and bound by Kim herself. For all that I scroll through the images of it at Kim’s online portfolio, I’m still captivated by that bright red of that debossed ironieteken. The world at large may have disdained their union, but I think irony and the ironieteken are made for each other.

I must thank Kim for keeping me up to date with her project — it looks fantastic, and, as someone who has just finished crudely stitching together a home-made photo album as a wedding anniversary gift for my wife, I am entirely in awe of the skill evident in Kim’s production of the finished article. If you’re interested in Kim’s work, follow her on Twitter or see more of her portfolio at Behance.

Apologies for the truncated post; the manuscript for The Book has just arrived back from W. W. Norton and I am rather giddily leafing through Brendan Curry’s edits in preparation for responding to them. Trust me when I tell you that it will be a much better book for his attentions!

- 1.

-

Jacobs, Bas. “Irony Mark, and the Need for New Punctuation Marks”. Underware, 2007.

Miscellany № 60: the secret life of the tilde

I am guilty of having somewhat ignored the tilde, or ‘~’, here at Shady Characters. Having just read Joseph Bernstein’s excellent, recent BuzzFeed article on the subject of “The Hidden Language of the ~Tilde~”,1 however, I thought I’d take a fresh look at this quirky sun-dried hyphen.

Joseph opens his article with a lament:

Last month in New York, Adam Sternbergh began his long cultural history of emojis2 by contrasting Face With Tears of Joy, the world’s most popular emoji, with the tilde, the venerable squiggle that is surfed on QWERTY keyboards by the ESC key and in math means approximately. Sternbergh pointed to the fact that Face With Tears of Joy has grown more popular on Twitter than the tilde as sufficient reason to offer tongue-in-cheek, if not Hearts in Eyes, advice to the ancient symbol:

“The 3,000-year-old tilde might want to consider rebranding itself as Invisible Man With Twirled Mustache.”

Unsettled by Adam Sternbergh’s abrupt dismissal of the poor old tilde, Bernstein proceeds to make the case for the tilde’s continuing relevance in the digital world, explaining that the ~bracketing tilde~ “unquestionably does something to [words], something destabilizing and a little uncanny […] a good definition of the use of bracketing tildes might go no further than adds juju.” Rather than recapitulate Bernstein’s arguments here, I thought a little context might be in order. Because when Sternbergh offhandedly mentions that the tilde is 3,000 years old, he is not far wrong — it may not be quite so ancient as that, but this little twiddle is the scion of a very long-lived family of marks.

Like the versatile octothorpe (#) and @-symbol, the modern tilde has a variety of uses. In mathematics it can be placed before a number to mean “approximately” (“~50” means “about 50”), or inserted between two variables to mean “x is equivalent to y”; in Boolean logic it stands for negation, or “not”; in tweets and other online discourse, as Joseph Bernstein says, it adds a sort of sarcastic or ironic emphasis to words;* and in the ubiquitous Unix-based operating systems on which the Web runs it is an alias for the home directory of the current user.

It is safe to say that its earliest adopters had none of these in mind.

One of the best clues to the origin of the tilde is to be found in the King James Bible, the “Authorised Version” that has lorded it over lesser translations of the Bible since the early part of the seventeenth century. In Matthew 5:18, as the King James version has it, Jesus says to his disciples:

For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled.3

The KJB was translated from a patchwork of Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Aramaic sources, with this particular line taken from the original Greek text of the New Testament. In the Greek, “jot and tittle” are rendered as iota and keraia respectively, where iota is the name of ‘ι’, the smallest letter of the Greek alphabet, and where keraia means a small hook, serif or diacritic mark used to modify written letters.3 (The linguistically diverse sources for the KJB, however, do leave some wiggle room for interpretation. The small Hebrew letter yodh (י) provides a tantalising alternative to iota, and ancient Hebrew scribes were well aware of how a keraia could transform one letter into another — ‘ב’, or B, is distinguished from ‘כ’, or K, only by the subtlest stroke of the pen.4)

But if iota (or yodh) is straightforwardly mapped onto “jot”, then what is a “tittle” and why was it chosen as the English counterpart for the Greek keraia? The Oxford English Dictionary explains that “tittle” comes from the Latin titulus, for “superscript” or “title”, and that it refers to a whole host of accents or other marks placed above letters or words to change their sound or meaning. A medieval a modified by an accent to form á, for example, became the long form of the vowel; an a drawn with a line above it (ā), on the other hand, represented an abbreviation beginning with a. And though we might more correctly call the acute accent (´) and macron (¯) by their formal names, they are both very much tittles — as are the dots at the top of is and js. As obscure as it is today, “tittle” is as accurate a translation for keraia as anything else; by talking of jots and tittles, the translators of the King James Bible let Jesus allude to the finer points of law by analogy with the smallest marks made by a scribe’s pen.5

You may have guessed where this is leading.

In the Latinate languages that preceded modern Spanish and Portuguese, a dash or ‘~’ placed above a vowel indicated the omission of a following n or m — a so-called nasal consonant — so that, for example, aurum, or gold, could be abbreviated to aurũ.6 As medieval Latin evolved into the modern languages of the Iberian peninsula, these missing nasal consonants gave rise to the “mouillé” sound found in Spanish (in the word señor, for example) and the nasally-inflected ã and õ vowels found in Portuguese.7 Thus the tilde was and is a tittle par excellence, a mark used to modify the sound or meaning of a letter. It was so exemplary of the form, in fact, that the word “tilde” itself arose from “tittle” sometime during the nineteenth century.8 In word and deed, the tilde is a tittle, with roots that twine through classical Greek writing, Latin vocabulary and Iberian speech.

- 1.

-

Bernstein, Joseph. “The Hidden Language Of The ~Tilde~”. BuzzFeed.

- 2.

-

Sternbergh, Adam. “Smile, You’re Speaking Emoji”. New York.

- 3.

-

Blue Letter Bible. “Greek Lexicon :: G2503 (KJV)”.

- 4.

-

Jones, Dr. Floyd Nolen. Chronology of the Old Testament. New Leaf Publishing Group, 2005.

- 5.

-

OED Online. “Tittle”.

- 6.

-

Sampson, Rodney. Nasal Vowel Evolution in Romance. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- 7.

-

OED Online. “Tilde”.

- 8.

-

Google Ngram Viewer. “Tittle,tilde”.

- *

- The tilde was even pressed into service as an explicit irony mark, as discussed some years back here at Shady Characters. ↢

Miscellany № 59: the percent sign

A few weeks back, Nina Stössinger asked on Twitter:

Isn’t it odd that the percent sign looks like “0/0” rather than, say, “/100” or “/00”?

This, it turns out, is a very good question. Like Nina, I had assumed that the percent sign was shaped so as to invoke the idea of a vulgar fraction, with a tiny zero aligned on either side of a solidus ( ⁄ ), or fraction slash. That said, something about those zeroes had always nagged at me. Specifically, as you divide any non-zero quantity by a smaller and smaller number the result tends ever closer to infinity (or rather, ±∞ as appropriate), until finally, when dividing by zero itself, you reach a mathematical singularity where the result cannot be computed — a numerical black hole of exotic properties and mind-bending implications. Throw in another zero as the numerator and you have a thoroughly nonsensical fraction. Though this is all terribly exciting from a philosophical point of view, it is not an especially useful situation to be in when trying to communicate the simple concept of division into hundredths. Either the ‘%’ had stumbled, blinking, from some secret garden of esoteric mathematics and into the real world, or there was more to the story. And so there was.

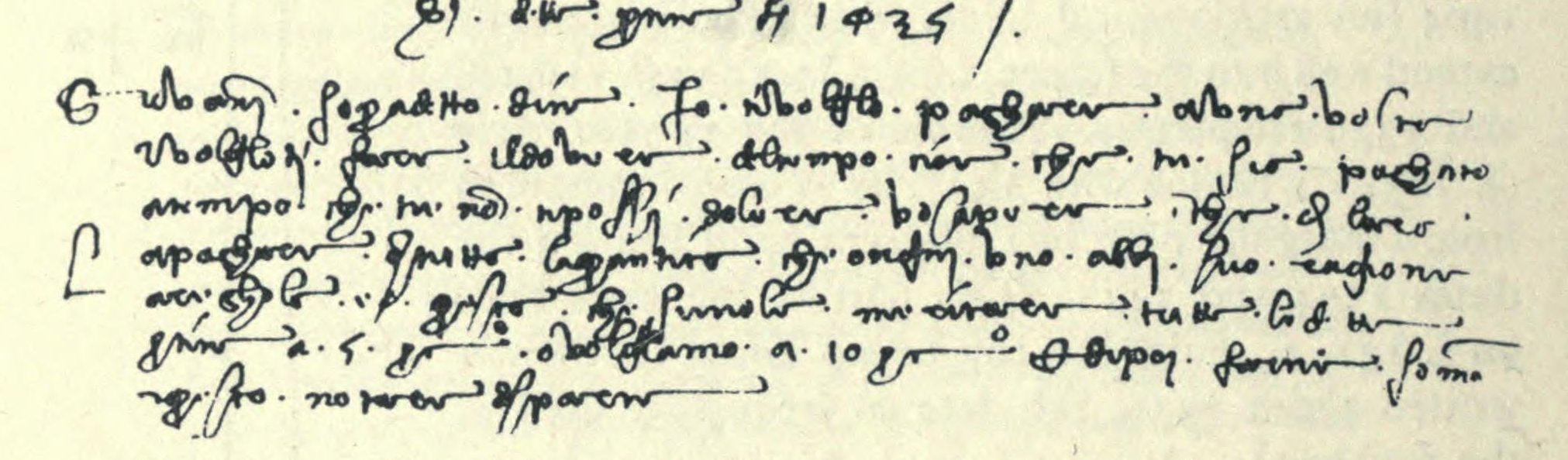

Writing in 1908, David Eugene Smith, later to be president of the Mathematical Association of America,1 reported on a peculiar find he had made in an Italian manuscript written sometime during the early part of fifteenth century. (Smith was cataloguing the mathematical holdings of one George Arthur Plimpton, a publisher and philanthropist who had amassed a huge library of ancient books.) What had caught Smith’s eye was an oddly attenuated abbreviation comprising a ‘p’, an elongated ‘c’, and a superscript ‘o’, or ‘o’, balanced upon the extended upper terminal of the ‘c’, as seen at top. From its context, Smith deduced that pco was a stand-in for the words per cento, or “per hundred”, more often abbreviated to per 100, p cento, or p 100.2 It was the first step towards a distinct percent sign — and, counterintuitively, it had precisely nothing to do with the digit zero.

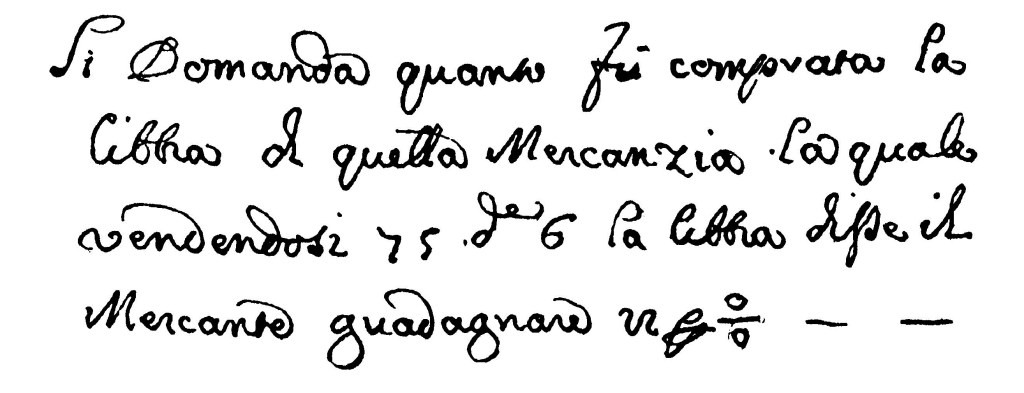

Smith picked up the trail with his weighty two-volume History of Mathematics, published in 1923,3 wherein he printed an image of the percent sign caught midway between pco and ‘%’. Taken from an Italian manuscript of 1684, as seen above, by now the word per had collapsed into the tortuous but common scribal abbreviation seen here while the ‘c’ had morphed into a closed circle surmounted by a short horizontal stroke. The imperturbable ‘o’ sat atop it. All that remained was for the vestigial per to vanish and for the horizontal stroke to assume its familiar diagonal orientation — a change that occurred sometime during the nineteenth century — and the evolution of the percent sign was complete.

Since then the ‘%’ has gone from strength to strength, and today we revel in a whole family of “per ————” signs, with ‘%’ joined by ‘‰’ (“per mille”, or per thousand) and ‘‱’ (per ten thousand). All very logical, on the face of it, and all based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how the percent sign came to be. Nina and I can comfort ourselves that we are not the first people, and likely will not be the last, to have made the same mistake.

- 1.

-

Fite, W Benjamin. “[Obituary]: David Eugene Smith”. The American Mathematical Monthly 52, no. 5 (1945): 237-238.

- 2.

-

Smith, David Eugene. Rara Arithmetica; A Catalogue of the Arithmetics Written before the Year MDCI, With Description of Those in the Library of George Arthur Plimpton, of New York. Boston: Ginn & company, 1908.

- 3.

-

Smith, David Eugene. History of Mathematics. Boston; New York: Ginn & company, 1923.

UK paperback competition: the winners!

Ladies and gentlemen: please put your hands together for Álvaro Franca and Yoni Weiss, winners of the UK paperback giveaway! Their names were picked at random from the set of all commenters, tweeters and Facebook users who replied, retweeted, or favourited the original posts about the competition.* (Both Álvaro (@alvaroefe) and Yoni (@yonimweiss) entered via Twitter.) Their copies of the UK paperback edition of Shady Characters will be on their way soon.

Commiserations if you did not win, but thank you nonetheless for all the tweets, comments and likes!

- *

- In more detail: I arranged the names of all entrants in a text file, then used random.org to pick two numbers between 1 and the total number of lines in that file. ↢