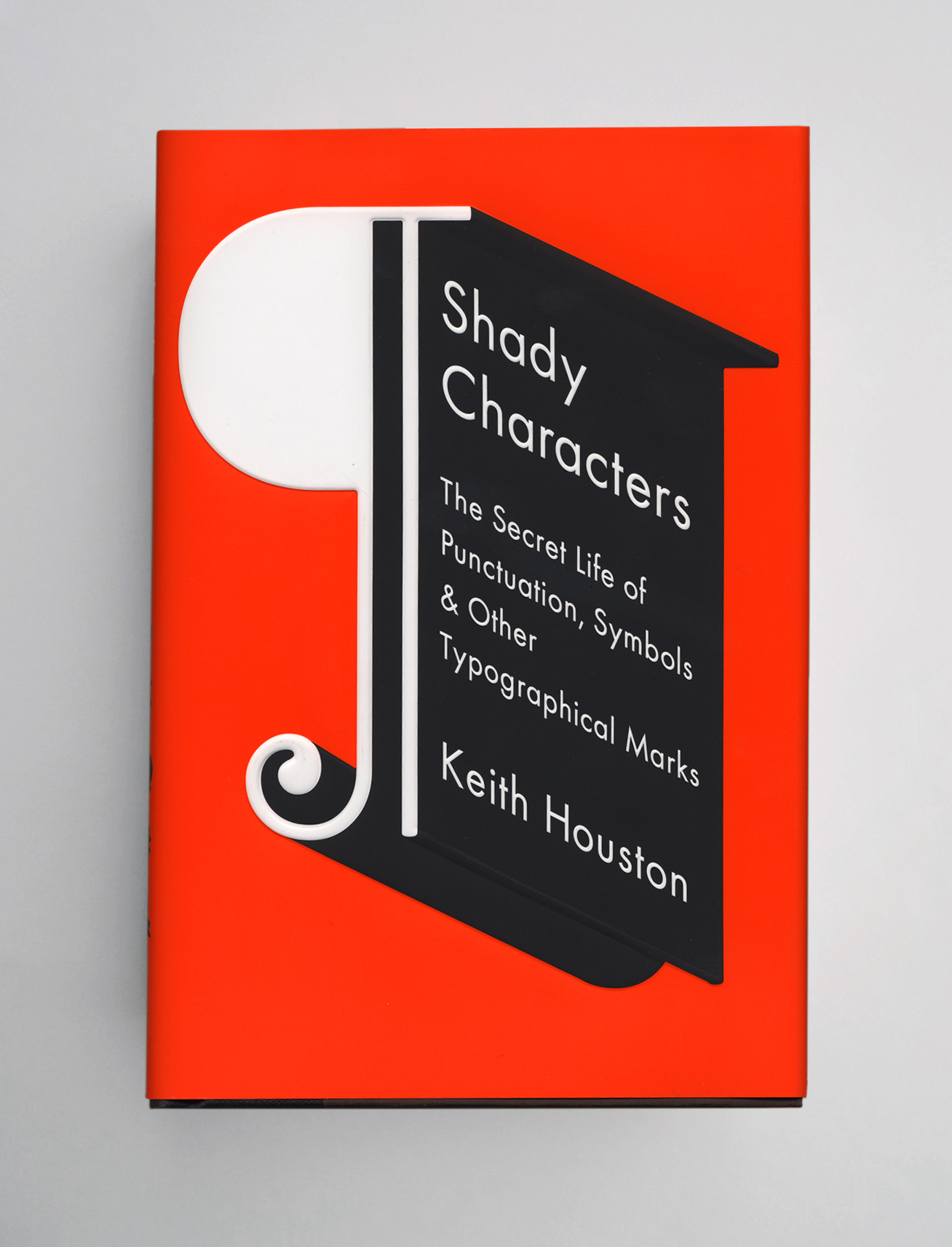

As I mentioned recently, I handed out copies of the Shady Characters quiz at the book launch party here in Edinburgh. I promised the attendees that one winner would receive a copy of the US edition of the book, and I’ve finally got round to tallying up the scores. Tom Pilcher and Chris Mackinnon both scored top marks, but random.org, my go-to source for numerical chaos, has selected Tom as the winner. Congratulations to Tom, commiserations to Chris, and thanks again to all who came to the launch and took part in the competition!