Emoji have been in the news recently for a host of reasons, most of them bad — but all of them, I would submit, worthy of our attention.

First up is a Netflix series called Adolescence that has been garnering plaudits in the UK and elsewhere since it went on air last month. I won’t spoil the plot, but I note that Emojipedia has joined the clamour with a blog post titled “Netflix’s ‘Adolescence’, Emoji Codes & Emoji Repurposing”. In it, Keith Broni explores the programme’s use of an “emoji code” by so-called incels — a misogynistic online culture of men who blame women for their lack of sexual success — in which, for instance, ‘💯’ refers to the belief that 20% of men attract 80% of women. Adolescence moots other codes too, such as ‘🔵’ and ‘🔴’ to represent the blue and red pills made famous by The Matrix, the Wachowski sisters’ dystopian action film, and which in turn relate to being “blue pilled” or “red pilled” — either accepting of mainstream views or “seeing through” them to some alleged hidden truth.

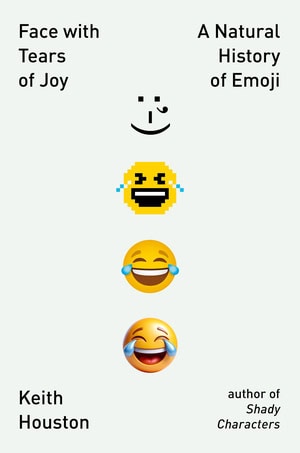

Despite the mild moral panic that has accompanied this use of emoji, Broni makes the point (echoed in Face with Tears of Joy) that in-groups often create temporary codes, or vocabularies, which take everyday words or symbols and give them new meanings. Emoji happen to be particularly ripe for this sort of jargon because they can have multiple interpretations based on the object or action being depicted, the name of that object or action, or metaphorical interpretations of either one.

I haven’t watched Adolescence yet (and to be honest, it does not seem like it will be an easy watch), but when I do I’ll be interested to see how this creative yet dispiriting use of emoji is handled.

Emoji only work because of the efforts of the Unicode Consortium, the body which governs text on the web and beyond. One of Unicode’s responsibilities is to define the technical mechanisms by which computerised text is encoded — that is, turned into bits and bytes — for storage or transmission. This has inevitably given rise to many special rules that address one nuance or another of written language.

Emoji have a number of such nuances. One in particular is the use of what are called “variation selectors”, which are invisible characters that can be used to choose between monochrome and colour versions of a given emoji. (For example, ‘😄︎’ versus ‘😄’.) There are lots of variation selectors in Unicode, but most are unused and computer programs generally ignore them unless they can do something useful with them.

So far, so innocuous. However, a software engineer named Paul Butler has found that it is possible to “smuggle” hidden meanings in emoji using long strings of unused variation selectors. Such hidden messages are not necessarily bad for one’s computer (and as Paul discovers, you don’t even need emoji to create them), but his blog post on the subject makes fascinating reading for anyone even tangentially interested in how computers process text.

A week is a long time in politics, as they say, and this week has been especially long. If you can, though, cast your mind back to the scandal that erupted barely a fortnight ago in which US Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, shared what appeared to be extremely sensitive military secrets in a group chat to which the editor of The Atlantic magazine had been unwittingly added.

If this wasn’t enough to be grappling with, it emerged that Hegseth’s correspondents cheered his news of attacks on Houthi insurgents with strings of emoji: Michael Waltz, an advisor to the Trump administration, posted “👊🇺🇸🔥”, while others expressed their gratitude with “prayer hands”, or ‘🙏’.

Honestly, I can’t even. I like emoji — I wrote a book about them! — yet even I can see that using them to celebrate a series of airstrikes is beyond the pale. It is emoji’s world now; we just live in it.