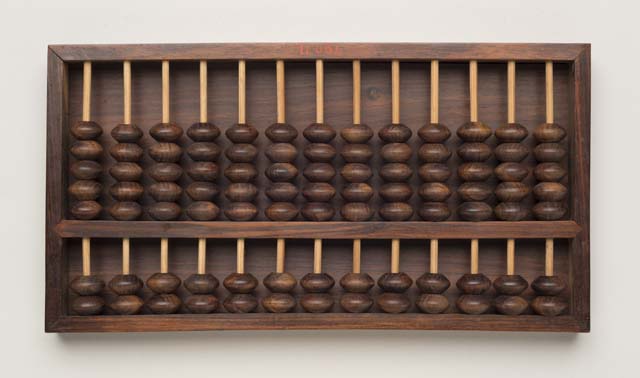

When it comes to calculating devices, China is synonymous with the abacus. But this is a comparatively recent development. For hundreds of years before the abacus appeared, numerate Chinese people used a different method of counting and calculating.

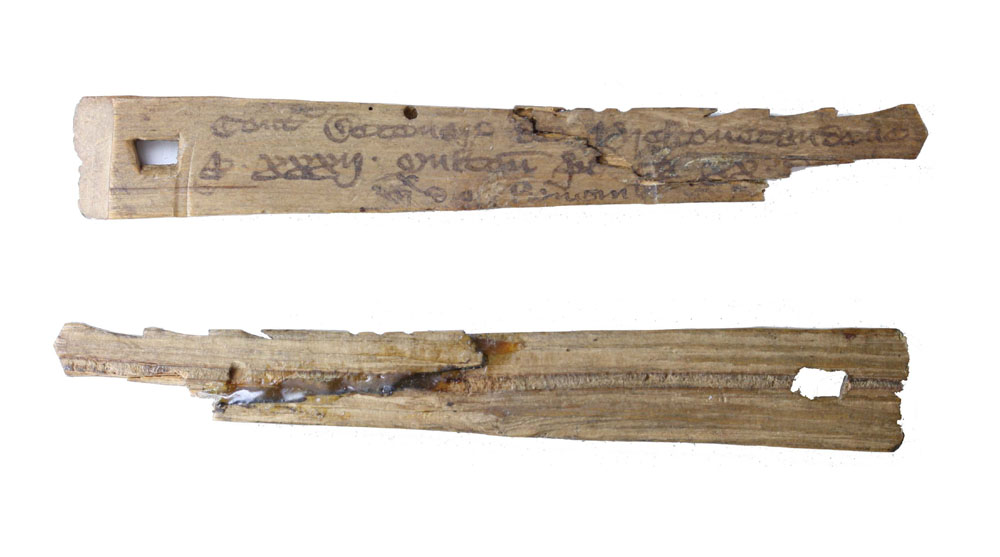

Counting rods (called ‘籌’, or chóu) were a system in which short bamboo rods were placed on a grid similar to a chessboard, with the rightmost column holding units, the column to its left tens, the column to the left of that hundreds, and so on. Thus, each row represented a complete number and each column represented a single digit, with the user taking as many rows as necessary to work through their mathematical problem.1 Rods even supported negative numbers, with rods standing for negative numbers marked with a black dot and those for positive numbers with a red dot.2

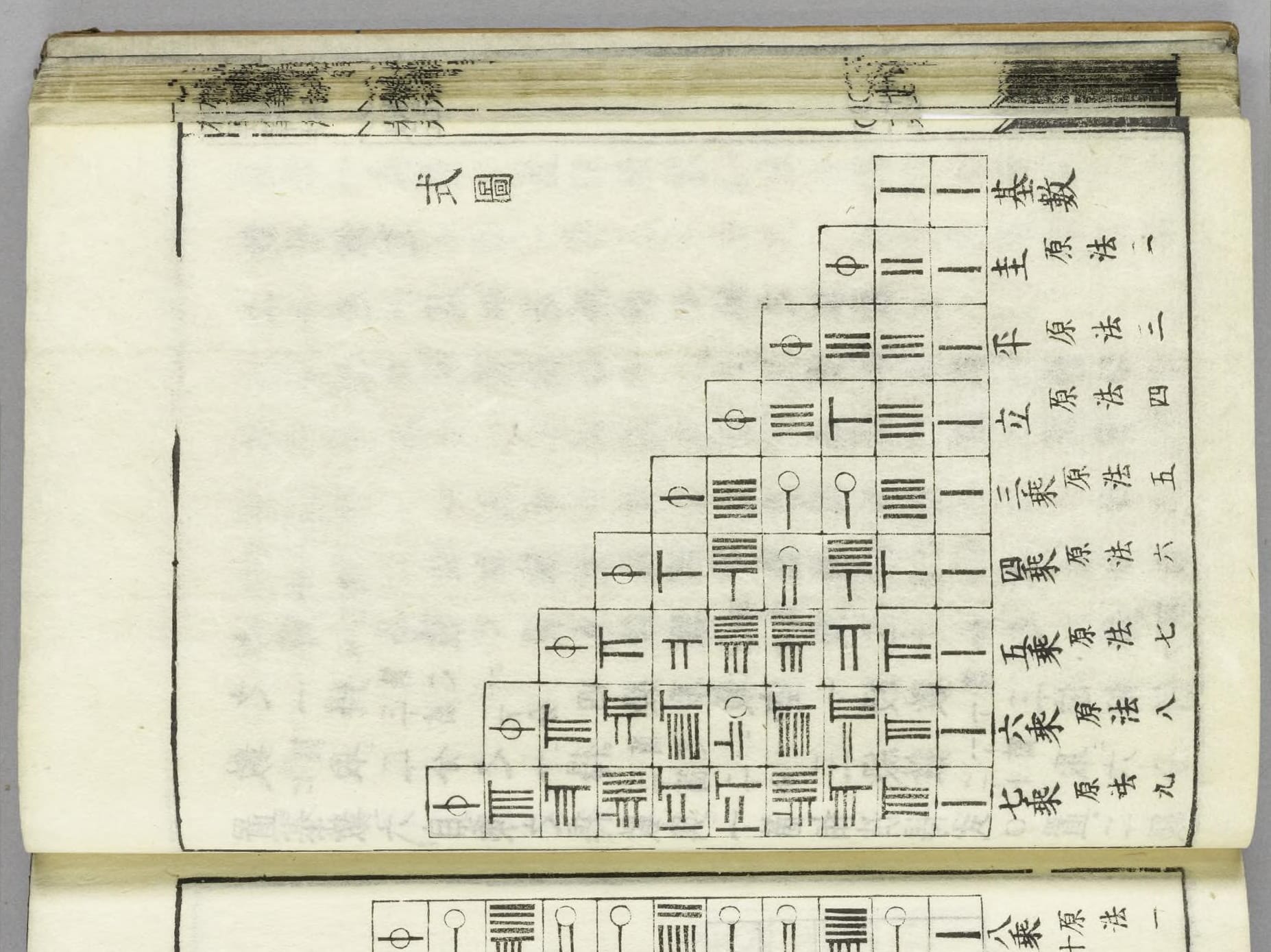

The rods inspired a written notation called rod numerals that boasted an easily-understood visual construction and a robust place-value system (neither of which could be said of the contemporary Roman numerals), and which even supported the concept of zero (which would not arrive in the West until the thirteenth century). By the end of the fifth century, China had used rod numerals to calculate pi to seven decimal places — a feat that would not be replicated elsewhere in the world until a thousand years later. Indeed, rods and rod numerals were so useful that they made their way into Korea and Japan, as would the abacus in years to come.3

Of course, rods and rod numerals have been thoroughly eclipsed by that later device. Yet the abacus contains echoes of the earlier system: each of an abacus’s columns, or wires, represents the digits 0 through 9, just like counting rods, and each column represents a new power of ten — again, just like counting rods.2 Moreover, most Chinese and Japanese abacuses split their rods into upper and lower sections, where the lower section’s four beads represent the values 1 through 4 and a single upper bead adds 5 to total 9. This mirrors rod numerals, where, for each digit, values 1 through 4 were represented by vertical rods (||||) and 5 was represented by a single, additional horizontal rod (–).

Comprehensive, portable, and easy to learn: counting rods and rod numerals were everything that their successor would turn out to be, lacking only, perhaps, in a little outright speed. They deserve better than to be forgotten.

- 1.

-

O’Connor, J J, and E F Robertson. “Chinese Numerals”. School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, 2004.

- 2.

-

Schwartz, Randy K. “A Classic from China: The Nine Chapters - Numbers and Units”. Mathematical Association of America. Accessed December 3, 2023.

- 3.

-

Swetz, Frank J. “Reflections on Chinese Numeration Systems: What Are Rod Numerals?”. Mathematical Association of America.