On Mastodon (or rather, on fediscience.org, a server powered by Mastodon), Marc Schulder asks:

What do you call the list of teaser phrases at chapter beginnings in novels like “Three Men in a Boat” or “Going Postal”?

So far I’ve found “epigraph”, which is not specific enough, and “taster”, which possibly is not what book people would call it.

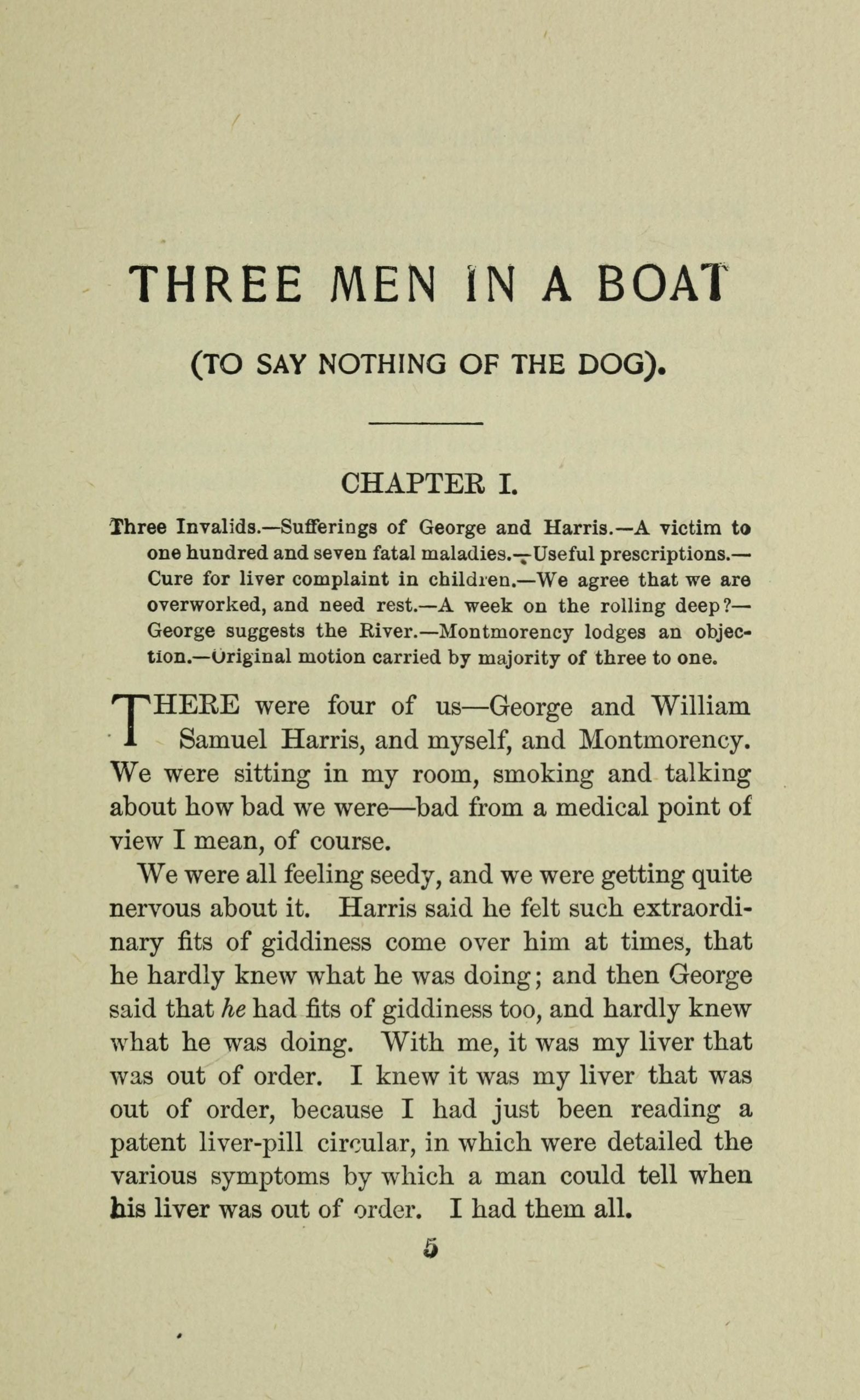

Courtest of the Internet Archive, here’s the first page of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, taken from an original 1889 edition:

For the avoidance of doubt, Marc is asking about this part:

Three invalids.—Sufferings of George and Harris.—A victim to one hundred and seven fatal maladies.—Useful prescriptions.—Cure for liver complaint in children.—We agree that we are overworked, and need rest.—A week on the rolling deep?—George suggests the River.—Montmorency lodges an objection.—Original motion carried by majority of three to one.

It’s a sort of table of contents, really, but rather than pointing to concrete locations in the text (such as catchwords or headers), it summarises the chapter’s contents instead.

I’ve seen this kind of thing before, as I’m sure many of us have, but it isn’t something I’d ever seen given a name. Some web searching did not turn up anything very convincing, and so I forwarded Marc’s query to my editor at W. W. Norton, Mr Brendan Curry. Brendan put Norton’s finest on the job and here, lightly edited, are their responses.

First up is Rebecca Homiski, Managing Editor. (Proposed terms are in small caps.)

My first hit was on a message board with some interesting asides; here, this feature seems to be referred to as a “nutshell.” The second search result was a New Yorker article about the history of the chapter, which definitely refers to this practice but dances around a term for it.

Rebecca also mentions this intriguing link:

And then came a brief discussion of tropes which referred back to “arguments” presented before sections of Renaissance-era poems.

Here, Rebecca links to the TV Tropes website, which is a wiki that catalogues many of the conventions, themes, and clichés that appear in TV programmes, films, books, and other forms of media. Collectively, tropes. Now, TV Tropes has a trope of its own in which the word “trope” is often used as a placeholder or boilerplate term. And so, the page that to which Rebecca links — the page that describes the practice of summarising the chapter of a book — is titled “In Which a Trope Is Described”. All of which is clever, but not especially pithy as a term of reference.

Ignoring that last term, then, we find that chapter summaries may be referred to as “nutshells” or, perhaps, “arguments”.

Don Rifkin, Associate Managing Editor, weighs in with a few more examples:

On this page, they’re referred to as “chapter contents”: “Chapter contents can be useful in histories or any book with long chapters that cover a variety of people or topics. This is like a mini Table of Contents specific to each chapter.”

Words into Type has a section on them and refers to them as “synopses” (p. 252, 3rd edition, 1974).

I see no consensus on a term for them, so I would think it’s fair game what to call them.

Okay then. Let’s add “chapter contents” and “synopses” to our list.

Robert Byrne, Trade Project Editor, adds a perceptive comment:

If they had a standard name, I suspect whatever it was may have been a specialized term mostly used in the publishing biz, which is maybe why it’s hard to find any literary connoisseurs and scholars mentioning them. Which is of course why we’re now desperate to know.

Well, quite.

Marian Johnson, editor of the Norton Anthologies, also contributed some of the same definitions we’ve seen above. I’m grateful to her, and to all at Norton who got their teeth into this question, and to Marc Schulder for asking the question in the first place. The answer to that question, then, as close as we can say, is that chapter summaries can be called “nutshells”, “arguments”, “chapter contents”, or “synopses”.